An industry image-dimension standard for film shooting and projection set by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1932, which dominated American and international motion picture production and exhibition until the early 1950s.

Film Explorer

A 35mm Technicolor reissue print of Singin’ in the Rain (1952), from the 1960s. Musicals of the Academy-ratio era emphasized duets, with full body framing in ways that were less effective in the widescreen era, which favored large group numbers.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

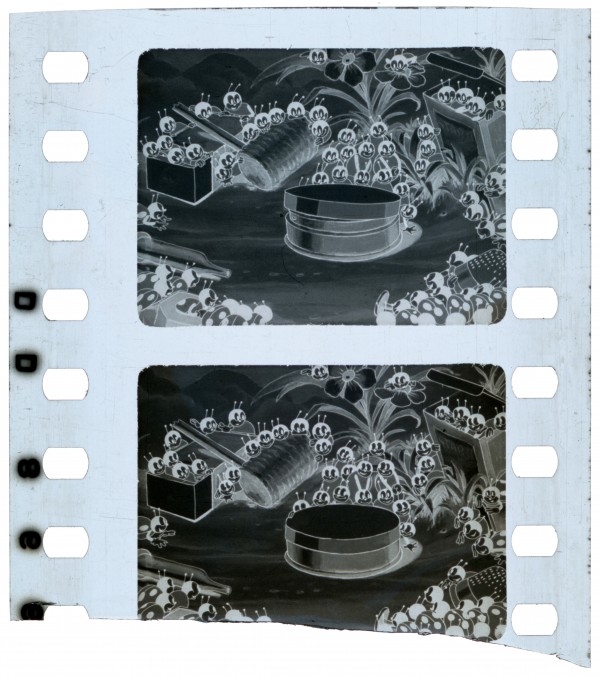

Outtake fragment from the camera negative for Bugs in Love (1932), shot with an Academy ratio aperture plate in the camera. This was the final Disney Silly Symphony short shot in B/W. The Silly Symphony series was Disney’s answer to the coming of sound, and from 1929–31 they used varying aspect ratios from 1.20:1 to 1.37:1, as they employed different sound technologies. Only beginning in 1932, with the imposition of the Academy ratio, did they consistently use the 1.37:1 ratio.

Film Frame Collection (P-074), Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

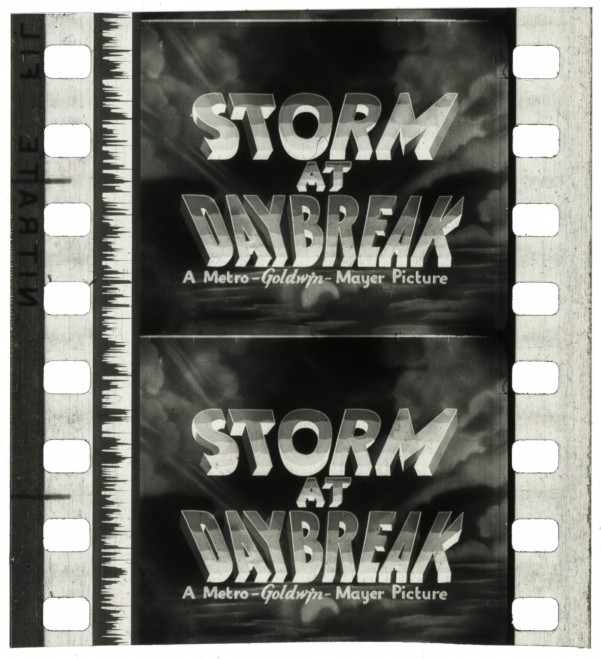

Many Academy ratio films were shot with a larger camera aperture, then cropped in projection to the Academy ratio of 1.37:1. This example from Storm at Daybreak (1933), would have been cropped at the top and bottom of each frame during projection.

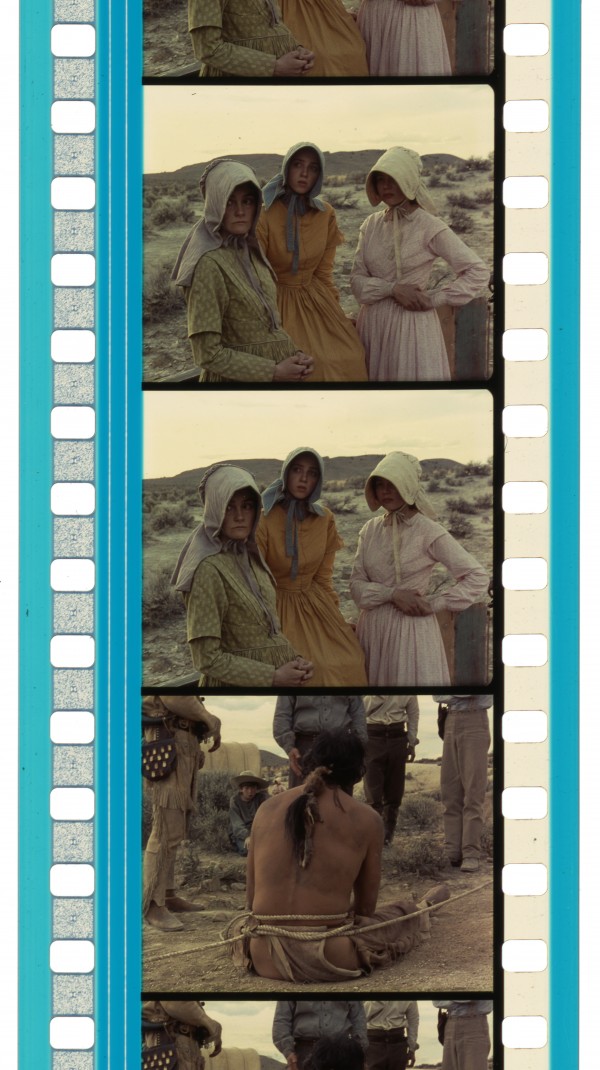

Although no longer common, some contemporary filmmakers continue to compose for the Academy aspect ratio. This 35mm print of Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff (2010) is intended to be cropped during projection to the Academy ratio of 1.37:1 .

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

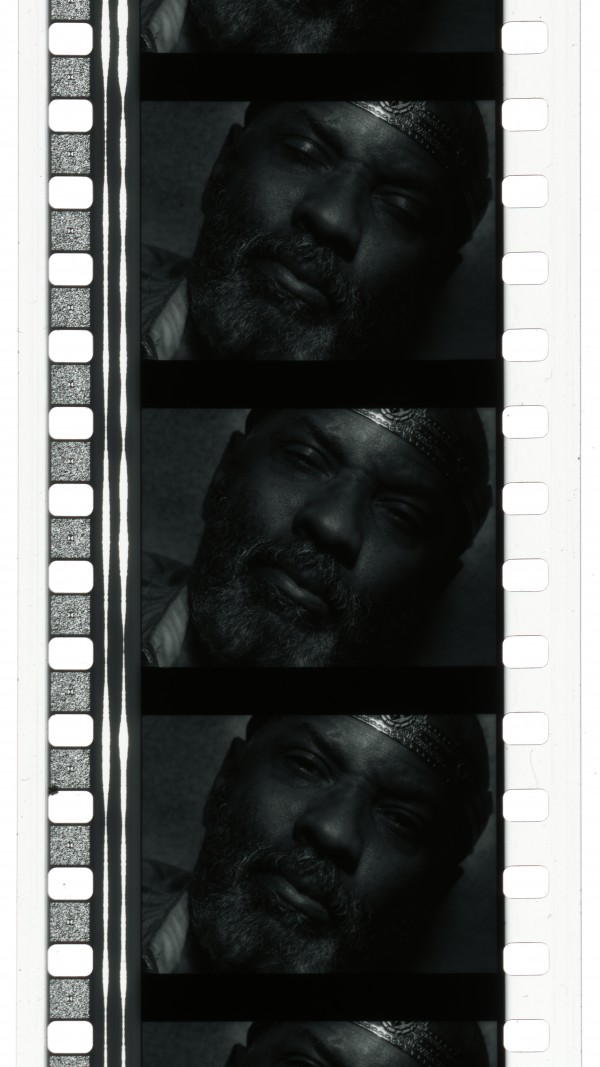

A rare 35mm print of Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021) featuring Denzel Washington in the title role. This film was shot digitally in the Academy aspect ratio.

Identification

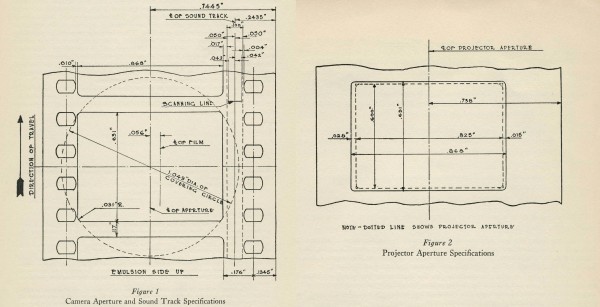

20.96mm x 15.24mm (0.825 in x 0.600 in).

1

Prints intended for Academy aspect ratio projection may be B/W or color.

The Academy aspect ratio was originally intended for use with an optical soundtrack, either variable area or variable density. The soundtrack area was 2.54mm (0.1 in) wide. The ratio was compatible with all later sound standards.

22.05mm x 16.03mm (0.868 in x 0.631 in).

History

In 1889, Thomas Edison’s assistant, W. K. L. Dickson essentially created the aspect ratio (relationship between height and width) for motion pictures that would be used by most filmmakers for more than six decades, at random (Belton, 1992). A 35mm-wide film stock with an image in a ratio of around four (width) to three (height) would be the industry standard from the earliest days of the silent era until the widescreen revolution of the early 1950s. Yet this is generally referred to as the Academy ratio, in reference to a 1932 decision by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) to impose particular dimensions as an industry-wide standard. The institution of the Academy ratio is a historical reality brought on by a unique set of circumstances, including the industry’s weariness of change in the wake of the conversion to sound production and the onset of the Great Depression.

Some of the earliest activities of AMPAS involved creating aperture standards for both cameras and projection. Though there were commonly used ratios, these had never been standardized and had been thrown in chaos both by the coming of sound and by several studios attempting experiments in wide-gauge film stock and widescreen, such as the 70mm Fox Grandeur and 65mm Vitascope formats. The introduction of sound-on-film technologies such as Movietone in the late-1920s, which created a narrower 1.19:1 image, meant theaters were having to creatively deal with the problem of the soundtrack appearing on the screen.

The Academy’s newly formed Technical Bureau took on this problem, looking at various theaters’ solutions, such as drapes, mattes, flippers, and using undersized aperture plates (AMPAS, 1929a: p. 3). A Subcommittee on Aperture Practice was convened within the Bureau, consisting of Virgil Miller (chair), Sidney Burton, Joseph Dubray, George Mitchell and Donald Gledhill. In 1929, the Bureau hastily assembled a recommendation that studios compose for sound-on-film in 0.835in by 0.620 in (21.21mm x 15.75mm), and theaters use an aperture on their projectors to project in 0.80 in by 0.60 in (20.32mm x 15.24mm) (AMPAS, 1929b). This was seen as a stopgap recommendation, rather than an industry-wide imposition.

Over the next couple of years, several studios attempted to introduce widescreen technologies, seeing this as the next area for innovation after the incorporation of sound. The Academy did not want to get involved, as it generally stayed away from any technologies it saw as competitive between the studios. Likewise, the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (SMPE) took a passive approach to industry practices – willing to analyze the pros and cons of various systems, but not to impose any kinds of standards.

After several widescreen/wide-gauge films were released in 1930 with little success, many in the industry turned against the technologies. Not only did they not want to invest in them, they did not want their competition to use them either. With the studios reliant on each other to show their films in each other’s theatres, it was economically advantageous to have everyone working with the same technologies. A concerted campaign began against wide film, with both MGM and Universal publicly declaring that they would have no wide films in their 1931–32 programs (Anon., 1931a: p. 8; Anon., 1931b: p. 1).

Now that the tide had turned against wide film and sound technology had stabilized, in the latter half of 1931, the AMPAS Technical Bureau convened a committee to gather data from the studios and theaters in order to form an industry standard for aperture (AMPAS, 1931a: p. 9). In focusing on the 4:3 ratio, the Academy invoked the tradition of Edison and presented it as a restoration of the most psychologically and aesthetically pleasing shape possible (AMPAS, 1931b: p. 3). Numerous economic advantages were mentioned, such as reducing the time needed to adjust the camera to various apertures, reduced variety of equipment and wattage in lighting, and building smaller sets. They claimed it would improve quality by allowing for “better composition” and more control over what would be seen in the theater. Likewise, the Academy enumerated several advantages for theaters, particularly the ability to do away with makeshift adaptations, and assurances that they would receive uniform prints from all of the studios.

The producers quickly agreed to the standard presented to them by the Technical Bureau. However, it took more negotiation to get the theaters on board. Harry Rubin, chief projectionist at Publix-Paramount, argued that the chosen ratio for exhibition favored the proportions of smaller houses and would actually penalize Class A houses, given that they would need to project at a picture-distorting angle to avoid their balconies (Anon., 1931c: p. 21). While Rubin fought to get the proposed 0.820 in x 0.615 in (20.83mm x 15.62mm) to 0.825 in x 0.590 in (20.96mm x 14.99mm) (approximately 1.40:1), when an Academy official met with the major chains and the Projection Advisory Council in New York, they agreed on a 0.825 in x 0.600 in (20.96mm x 15.24mm) compromise (Anon., 1931: p. 10). SMPE approved the dimensional standards for 35mm camera and projector aperture at their May 1932 meeting with no mention of where the standards came from (Anon., 1932: p. 924). With Hollywood films dominant across the globe, the Academy ratio likewise became an unofficial international standard used by producers and exhibitors around the world.

The Academy’s ratio was a work of compromise and consensus, built on a vague artistic theory about an ideal shape. Yet it ultimately parroted a proportion chosen by Dickson decades earlier. Although Academy ratio required new aperture plates, it allowed theaters to return to the masking and proscenium practices that they had followed in the silent era without a significant investment in new equipment. The Academy ratio merely reduced the aperture height to recreate a familiar ratio, mitigating the way the width had been reduced by the addition of the optical soundtrack. It proved easier to gain agreement on the ratio everyone had grown accustomed to than to get everyone to agree on a new, wider look for the motion pictures.

This standard remained consistent until the industry was broken open in the 1950s by changing economic incentives, industry structures, and technologies such as CinemaScope. With the industry once again in flux and looking to bring back audiences lost to television, studios reintroduced widescreen technologies, likewise opening the door to great aperture experimentation (including cropping Academy ratio films into a variety of wider ratios). While the Academy ratio seemed to disappear from Hollywood seemingly overnight, it continued to thrive in international and art house cinema and experienced revival once nostalgia for the bygone era set in.

In recent years, the resurgence of the Academy ratio – in films from The Artist (2011) to The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021) – has been seen as a throwback to the time when the ratio dominated the world’s screens. However, current filmmakers’ ability to choose the ratio – which is one among several possibilities, including the more common 1.85:1 and 2.35:1 – is indicative of changes in exhibition that have made it easier to switch between formats. Today’s theaters require only the flip of a switch to move curtains into various screen shapes. A film such as The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) is able to use multiple aspect ratios without causing problems in exhibition in ways that were impossible in prior decades.

Selected Filmography

One of the first films released in the Academy aspect ratio, listed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as one of the “First Releases for Universal Projector Aperture”. Since the ratio had been in use on some films prior to the imposition of the standard, they were able to label films already in theaters as “released under the universal projector aperture”.

One of the first films released in the Academy aspect ratio, listed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as one of the “First Releases for Universal Projector Aperture”. Since the ratio had been in use on some films prior to the imposition of the standard, they were able to label films already in theaters as “released under the universal projector aperture”.

One of the first films released in the Academy aspect ratio, listed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as one of the “First Releases for Universal Projector Aperture”.

One of the first films released in the Academy aspect ratio, listed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as one of the “First Releases for Universal Projector Aperture”.

One of the first films released in the Academy aspect ratio, listed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as one of the “First Releases for Universal Projector Aperture”.

One of the first films released in the Academy aspect ratio, listed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as one of the “First Releases for Universal Projector Aperture”.

Example of the Academy ratio used with Technicolor, shortly before it declined as the dominant aspect ratio in Hollywood production.

Example of the Academy ratio used with Technicolor, shortly before it declined as the dominant aspect ratio in Hollywood production.

Example of the continued use of the Academy ratio in international art cinema, well after the ‘widescreen revolution’ had caused it to virtually disappear from Hollywood production.

Example of the continued use of the Academy ratio in international art cinema, well after the ‘widescreen revolution’ had caused it to virtually disappear from Hollywood production.

Example of the revival of the Academy ratio since the widespread conversion to digital production and exhibition.

Example of the revival of the Academy ratio since the widespread conversion to digital production and exhibition.

Technology

The Academy sent a memo to the studios on February 16, 1932 specifying that their cameramen should all begin using a camera aperture of 0.868 in x 0.631 in “effective immediately” (AMPAS, 1932: p. 3).

In the Academy’s literature (it produced a total of over 140,00 leaflets) for theaters across North America, it described the new standard for projection. It emphasized that the standard was meant to “reduce the difficulty of exact framing and to do away with the variety of apertures and interchangeable devices” then in use. Theaters would be able to identify films using the new standard by recognizing that the frame lines were four times as wide as previously with no change to sprocket holes or soundtrack. The theaters would need to make “an initial minor adjustment to aperture plates and projection screen masks” to reach the new uniform projection aperture of 0.600 in high x 0.825 in wide, with a center line 0.738 in (18.75mm) from the edge of the film on the soundtrack side. They also specified that they should frame from the top of the picture “in order to allow the head room intended in the photography”.

The projection aperture was slightly different for viewing daily footage at the studio viewing room. They suggested a larger 0.846 in by 0.626 in with a center line 0.7415 in (18.83mm) due to additional shrinkage that would be likely after printing. This allowed for eight mils (0.203mm) on the soundtrack side and fourteen mils (0.356mm) on the other for “tolerances and shrinkages” (AMPAS, 1932: p. 5). While the standards were universal, means of achieving them were not necessarily so. Sometimes, the Academy ratio was printed into the image with thick black frame lines (hard matte) and sometimes the image was cropped during projection to constitute the ratio (open matte). As such, despite efforts to make motion picture production as standardized and systematic as possible, in the end, it remained highly varied and artisanal.

References

AMPAS (1929a). “Technicians Working for Standardized Apertures”. Academy Bulletin, 39 (August 20): p. 3.

AMPAS (1929b). “Memorandum of Committee Meeting in Academy Lounge” (August 22). Academy Archive, Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills, CA, United States.

AMPAS (1931a). “Practical Problems Basis for Technical Program”. Academy Bulletin, 40 (September 21): p. 9.

AMPAS (1931b). “Academy Moves to Secure Important Screen Standard”, Academy Bulletin, 41 (November 25): p. 3.

AMPAS (1932). “Uniform Aperture Specifications”. Technical Bulletin, Supplement No. 6, (July 1): pp. 3–5. https://digitalcollections.oscars.org/digital/collection/p15759coll4/id/257/rec/24 (accessed October 1, 2024).

Anon. (1931). “Cowan Obtains Approval on New Standard Frame”. Motion Picture Herald (December 19): p. 10.

Anon. (1932). “Society Announcements”. Journal of the SMPE, 19:1 (July): p. 924.

Belton, John (1992). Widescreen Cinema. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: pp. 15–22.

Film Daily (1931a). “New Universal Program to Be Launched by April”. The Film Daily (May 25): p. 8.

Film Daily (1931b). “Nick Schenck Favors Stars Over Wide Film and Color”. The Film Daily, 56:75 (September 27): p. 1.

Marzola, Luci (forthcoming). “The Academy Ratio: Standardizing Film in Early Sound Hollywood”. In Kirsty Sinclair Dootson, Pansy Duncan & Alice Lovejoy (eds), Film Stock: Histories, Technologies, Aesthetics. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Motion Picture Projectionist. (1931). “Aperture Makes Projection History”. Motion Picture Projectionist (September): p. 21.

Patents

Compare

Related entries

Author

Luci Marzola is a film historian specializing in the early Hollywood technology and labor. Her research has been published in the volumes Oxford Handbook of Silent Cinema (2024) and Moving Pictures: Karl Struss and the Rise of Hollywood (2024) as well as the journals Film History, Historical Journal of Film, Television, and Radio, and The Velvet Light Trap. Her book Engineering Hollywood: Technology, Technicians, and the Science of the Studio System (Oxford University Press, 2021) was the 2022 recipient of the CEMI Best Book Award from the Media Industries SIG of SCMS. Her edited volume, co-editing with Kate Fortmueller, Hollywood Unions is forthcoming from Rutgers University Press. She is the Academic Director of and teaches in the Division of Cinema and Media Studies at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts.

I’d like to thank Kirsty Sinclair Dootson, Pansy Duncan, and Alice Lovejoy who gave invaluable feedback on this research while developing the chapter for their volume.

Marzola, Luci (2024). “Academy ratio”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.