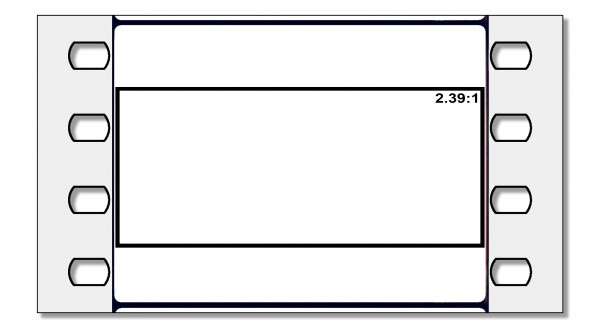

A widescreen format that extracted a flat 2.39:1 image and reformatted it into an anamorphic frame.

Film Explorer

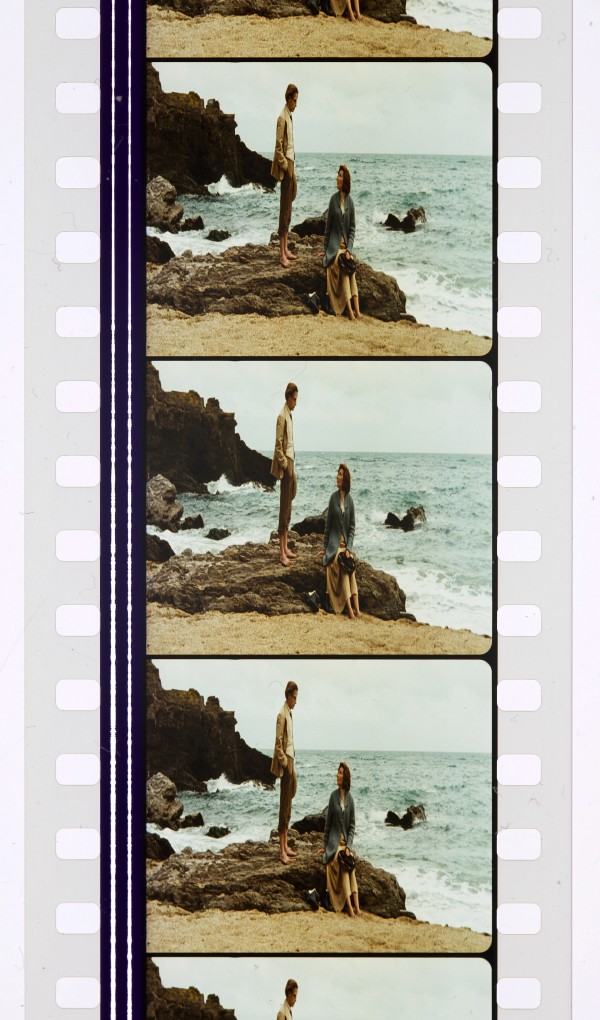

Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (Hugh Hudson / Warner Bros, UK/US 1984). Greystoke was the first production shot in Super 35, originally branded as Super Techniscope.

Academy Film Archive, Hollywood, CA, United States.

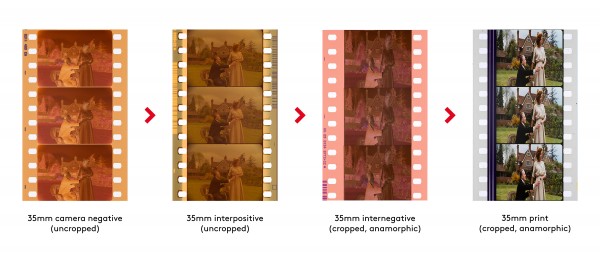

The 35mm original camera negative of Howards End (1992). Super 35 camera negatives are typically photographed uncropped using the full width of the film. A 2.39:1 widescreen image can be extracted from a portion of this frame.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

A 35mm release print of Howards End (1992). A 2.39:1 widescreen image was extracted from the uncropped image that was photographed, jettisoning the unwanted top and bottom of the image. Additionally, a 2:1 anamorphic squeeze was applied in post-production to compress the image horizontally on the film print.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

21.29mm x 17.78mm (0.838 in x 0.700 in) (anamorphic project aperture).

Camera negative edge numbers never translated to the anamorphic interpositive or print, because of the optical step involved. Standard edge print should be apparent on prints.

Super 35 camera negatives are always cellulose triacetate; from the mid-1990s, Super 35 pre-print elements and release prints are most likely polyester.

1

Most Super 35 releases were in color.

Super Techniscope on Silverado (1985), otherwise the format generally goes uncredited.

Compatible with a range of soundtrack options, including optical, Dolby Digital, Dolby SR-D, DTS, and SDDS.

The Super 35 uncropped full aperture frame was 24.89mm x 18.66mm (0.980 in x 0.735 in). There was never a SMPTE standard set for Super 35. Depending on the camera and the laboratory, the 2.39:1 extraction from the full aperture fame could be: 23.61mm x 9.83mm (0.930 in x 0.387 in) Technicolor, Hollywood; 24.10mm x 10.52mm (0.949 in x 0.414 in) Technicolor, London; 24mm x 10mm (0.945 in x 0.394 in) Panavision & MGM Labs.

Super 35 increasingly began to be shot in 3-perforation format as digital intermediate workflows became more common in film production.

For best quality, slower speed (finer grain) camera negative stocks were used so that optimal image quality would be retained when optically printing anamorphic elements. When digital intermediates were utilized, slow-speed camera negative film stocks became less important.

Standard camera negative edge numbers or Keycode.

History

[Author’s Note: I worked at Technicolor Hollywood during the 1980s, as one of the principal liaisons between film productions and the laboratory. I was closely involved in the refinement of Super 35. This entry is informed by my own experiences as well as interviews and anecdotes with other contributors to the format.]

Despite remarkable similarities, the development of the Super 35 format in the 1980s was done without any prior knowledge by those involved in the Superscope and Superscope 235 formats of the 1950s. This is according to Joe Dunton, cinematographer on Dance Craze, the first film to adopt some of the reformatting principles of Super 35.

Super Techniscope

In 1982, cinematographer John Alcott, BSC approached Les Ostinelli of Technicolor about his upcoming project, Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984). The director Hugh Hudson wanted to shoot the film in the anamorphic widescreen aspect ratio of 2.39:1. However, the only anamorphic format of quality was provided by Panavision and Alcott was loath to work with Panavision due to a disagreement he had, early in his career, with Panavision founder Robert Gottschalk. Added to this, director Hudson had his own Arri BL cameras, which he wanted to use on the film if possible.

Alcott approached Ostinelli for any ideas on how he could achieve the 2.39:1 aspect ratio shooting spherically with the Arri BL cameras, without the graininess associated with the 2-perforation Techniscope format. Spherical lenses also had the benefit of allowing Alcott to shoot at a wider aperture than with anamorphic lenses, helping compensate for low light levels in the jungle locations.

Based on his involvement with Dunton’s image reformatting on Dance Craze (enlarging a 35mm frame to 70mm), Ostinelli suggested to Alcott the possibility of composing the 2.39:1 aspect ratio within the 35mm full aperture frame and, using Technicolor’s optical printers, have the image blown-up and squeezed to fit within a standard anamorphic 35mm interpositive, contact printed to a 35mm internegative from which release prints would be struck.

Alcott shot some tests and enthusiastically decided this is how he would shoot Greystoke. According to Joe Dunton, it’s possible that Technicolor’s Les Ostinelli didn’t inform Alcott about Dunton’s work on Dance Craze, which may have been why Alcott took credit for the idea and named the process Super Techniscope at the time. John Alcott went on to photograph his last four films after Greystoke in the Super Techniscope/Super 35 format.

As the format became more popular, the name Super Techniscope fell out of favor with other film laboratories and camera rental houses that didn’t want to call attention to Technicolor’s ‘contribution’ to the development of the format. As such, the more generic name Super 35 was adopted by camera rental houses and laboratories in the mid-to late 1980s, utilizing the same name first coined by Joe Dunton for when he used a 35mm full aperture image intended for enlarging to 70mm prints.

Silverado, Alternate Aspect Ratios, and Common Center

Silverado (1985) was the first film after Greystoke to be photographed in the Super 35 format (still credited as Super Techniscope in the film’s credits).

Because the spherical lenses used for Super 35 are half the focal length of an anamorphic lens covering the same field of view, there is potential for greater depth of field at a given aperture. This was the impetus for the film’s cinematographer John Bailey, ASC, to choose Super 35, as it allowed most compositions to be photographed with almost everything in focus in any given shot.

It was also at this time that executives at Columbia Pictures, started envisioning that Super 35 could be a “one format fits all” by increasing the vertical height of the frame. By doing this, a 1.85:1, 1.66:1, or even a 1.37:1 (4:3 for video) image could be extracted. Arguing that with very little effort, the video master for television broadcast and VHS home video release could be yielded almost automatically. Letterboxing of films was not yet a widespread practice.

Cinematographer Bailey balked at the idea that the compositions could be carelessly altered and argued that a long shot of a Silverado gunslinger standing in the street in the 2.39:1 composition, would be altered to become an extreme long shot, with the character so small in the frame as not to be recognizable. Stating that a pan-and-scan of the image, as objectionable as it was in comparison to a letterbox presentation, would be preferable to a wholesale alteration of the composition.

In order to ensure that alternate aspect ratios were not thoughtlessly extracted from Silverado, Bailey had a 2.2:1 hard matte created for the camera aperture, resulting in a widescreen image photographed onto the full width of the camera negative. This ensured that a 70mm extraction could be made from the frame, but nothing “taller” than 2.2:1 could be created without input from the filmmakers.

At the time Silverado was produced, involvement by cinematographers in formatting for video was not as assured as it is today. As such, many home video releases in the late 1980s and 1990s used the full uncropped 1.37:1 image rather than the original theatrical widescreen compositions.

Common Topline

“Common Topline” evolved from this discussion. In this method, the 2.39:1 composition was positioned at the top of the full aperture frame instead of in the center. All extracted aspect ratios had the same top, or headroom, of their compositions with alternate aspect ratios achieved by lowering the bottom of the frame.

Many cinematographers would customize where the top line would be positioned within the full aperture frame. In some cases, with enough headroom that the 1.85:1 and 1.37:1 extractions would increase a bit of the top of the image extraction, while increasing most of it below the 2.39:1 area. As such, there was never a standardized Common Topline extraction as it depended on the individual filmmaker’s desire of where to position the framing within the full aperture area.

Some filmmakers like James Cameron used the common topline technique with great success in adapting films like Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), True Lies (1994) and Titanic (1997) to be carefully reformatted for 1.33:1 (4:3) televisions. However, Cameron’s approach was by no means a one-size-fits-all extraction. A close examination of his films shows that each cut was optimized to the best extraction for the image in its adaptation for the 4:3 television screens of the time.

The 1990s saw an unprecedented growth in filmmakers’ desire to compose their films in the 2.39:1 aspect ratio. Equipment supplier Panavision found that the Super 35 format empowered filmmakers to compose films in the 2.39:1 aspect ratio, whether or not anamorphic lenses were available – and at times they struggled to meet this demand. This also enabled other camera rental houses, without anamorphic lenses, to offer solutions for Super 35 photography. By the end of the 1990s, more films were being shot worldwide in the 2.39:1 aspect ratio than ever before (both Super 35 and anamorphic). This trend continues to the present.

The Super 35 full aperture frame composed for a 2.39:1 aspect ratio, as it was for Greystoke. Later this would be called “common center”.

Courtesy of Rob Hummel.

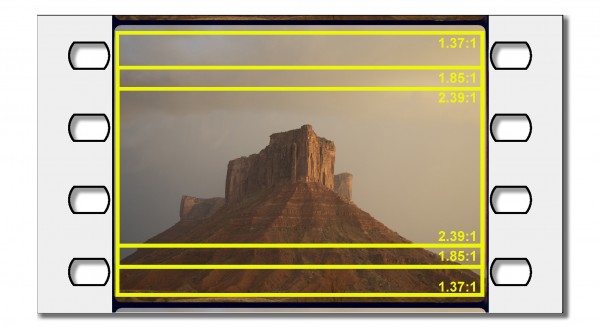

35mm frame composed for a 2.39:1 Common Center Super 35 image extraction. The alternate aspect ratios of 1.85:1 and 1.37:1 can be extracted by using more of the original frame.

35mm frame composed for a 2.39:1 Common Topline Super 35 image extraction. The alternate aspect ratios of 1.85:1 and 1.37:1 can be extracted by using more of the original frame.

Selected Filmography

Ron Howard used the Super 35 format on most of his features in the 1990s. Cinematography by Dean Cundey, ASC. Laboratory work by Deluxe, Hollywood, CA.

Ron Howard used the Super 35 format on most of his features in the 1990s. Cinematography by Dean Cundey, ASC. Laboratory work by Deluxe, Hollywood, CA.

Martin Scorsese used common top and 3-perforation photography on many of his features. On The Departed, a digital intermediate workflow was used in preparing the final anamorphic composition. Cinematography by Michael Ballhaus, ASC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

Martin Scorsese used common top and 3-perforation photography on many of his features. On The Departed, a digital intermediate workflow was used in preparing the final anamorphic composition. Cinematography by Michael Ballhaus, ASC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

The first film photographed in Super 35. Cinematography by John Alcott, BSC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

The first film photographed in Super 35. Cinematography by John Alcott, BSC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

Super 35 with a digital intermediate workflow. Cinematography by Eduardo Serra, ASC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

Super 35 with a digital intermediate workflow. Cinematography by Eduardo Serra, ASC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

This film used the common center technique. Cinematography by Tony Pierce Roberts, BSC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, London, United Kingdom.

This film used the common center technique. Cinematography by Tony Pierce Roberts, BSC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, London, United Kingdom.

Cinematographer John Bailey used a hard matte in the camera to photograph a 2.2:1 widescreen frame. This was reformatted to an anamorphic aspect ratio of 2.39:1 for 35mm release prints. Cinematography by John Bailey, ASC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

Cinematographer John Bailey used a hard matte in the camera to photograph a 2.2:1 widescreen frame. This was reformatted to an anamorphic aspect ratio of 2.39:1 for 35mm release prints. Cinematography by John Bailey, ASC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

James Cameron used common top framing for most of his movies, beginning with The Abyss (1989). Cinematography by Adam Greenberg, ASC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

James Cameron used common top framing for most of his movies, beginning with The Abyss (1989). Cinematography by Adam Greenberg, ASC. Laboratory work by Technicolor, Hollywood, CA.

It was determined on Top Gun that cameras with anamorphic lenses would not fit into the fighter jet cockpits for the aerial sequences in the film. Rather than mix formats, the entire film was shot in Super 35. Cinematography by Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC. Laboratory work by Metrocolor, Culver City, CA.

It was determined on Top Gun that cameras with anamorphic lenses would not fit into the fighter jet cockpits for the aerial sequences in the film. Rather than mix formats, the entire film was shot in Super 35. Cinematography by Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC. Laboratory work by Metrocolor, Culver City, CA.

Technology

When converting a flat Super 35 negative to a squeezed 35mm anamorphic release print, the printing steps need to be carefully considered in order to minimize grain and maximize sharpness. While working on Silverado at Technicolor, Hollywood, we found that there were noticeably different results in the final 35mm anamorphic composite prints, depending on which optical printing path was used.

Because the anamorphic film frame has approximately 53 per cent more negative area than Super 35’s 2.39:1 extraction, Super 35 has the potential to result in a much grainier image than anamorphic, after going through the optical steps of a traditional photochemical laboratory workflow.

On Silverado, the tests that were performed by John Bailey and Rob Hummel determined that the production could take advantage of the planned 70mm release of the film by first enlarging the Super 35mm frame (in this case the 2.2:1 composition) to a 65mm interpositive (IP); while for 35mm prints, the 65mm IP image was reduced into a 35mm internegative (IN) optimized for the 2.39:1 composition. By enlarging to the 65mm format first, this mitigated against visible grain in the release print to a great extent.

However, not all films included a 70mm release, so the author experimented further and found that the highest quality 35mm duplicating elements for Super 35 were yielded using the following workflow:

1. Optically blow-up and squeeze the original Super 35 2.39:1 composition to fit within a 35mm interpositive (IP) projection aperture, intentionally overexposing the IP in the process;

2. Under developing (pull process) the overexposed IP, yielded much less apparent grain in this element;

3. Contact print the anamorphic IP to a 35mm anamorphic internegative (IN);

4. Strike composite release prints from the 35mm IN. The results were very pleasing and very cost effective for the studios, because manufacturing additional printing negatives only involved making a simple contact print from the 35mm IP to the 35mm IN.

This workflow was used successfully on several Super 35mm films at Technicolor. In side-by-side comparisons it yielded printing elements indistinguishable from those manufactured using a 65mm IP.

Unfortunately, the Technicolor lab ceased promoting the technique of building the anamorphic squeeze into the IP element, as they could generate greater income by charging for an optically created IN each time a new printing negative was needed. They still overexposed and underdeveloped the IP element, but by moving the blow-up and squeeze to the next stage of the workflow resulted in an image quality slightly inferior to elements created where the optical step was implemented at an early stage. The results were “good enough” – most filmmakers didn’t realize their films could look even better.

At least one other laboratory’s approach to making superior Super 35 printing elements was to incorporate first blowing-up to a 65mm IP and then reducing to a 35mm scope IN – the approach adopted on Silverado. This method was, of course, more expensive than the over exposed IP approach, but Technicolor kept this technique a closely guarded secret. Overexposing and under-developing a film element is a well-known method for mitigating against film grain, but it hadn’t occurred to other laboratories to take this approach.

It should also be mentioned that when the same image was photographed in both Super 35 and anamorphic 35mm, the anamorphic original always yielded a superior image quality from a sharpness and grain standpoint due to it having over 50 per cent more negative area than Super 35.

In 2001, with the advent of 2K digital intermediate (DI) workflows in post-production, the Super 35 image benefitted by the elimination of the multiple optical printing steps that had been used previously.

With a DI, once the camera negative is scanned, it is color corrected and anamorphically squeezed in an effectively digital lossless environment. When a film print is still desired, that digital imagery is sent to a digital film recorder for outputting to a 35mm film, bypassing all the image degrading steps the photochemical optical path would have introduced.

Original production elements for Howards End (1992). On this production, Technicolor Ltd. in London cropped and anamorphically-squeezed the image at the internegative stage. The camera negative and interpositive show the full uncropped image.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States. Diagram by Oleksandr Teliuk.

References

Anon. (1984). Super Techniscope Camera Specifications. Courtesy of Rob Hummel.

Anon. (1985a). Super Panavision 35 Camera Specifications. Courtesy of Rob Hummel.

Anon. (1985b). Super Techniscope Post Production Pricing. Courtesy of Rob Hummel.

Anon. (1985c). Super Techniscope Printing Workflows. Courtesy of Rob Hummel.

Dunton, Joe (2022). Facebook Messenger interview with Robert Hummel, December 8, 2022.

Goi, Michael & American Society of Cinematographers (2013). American Cinematographer Manual (10th edn). Hollywood: CA: American Society of Cinematographers.

Mullen, M. David, Rob Hummel and American Society of Cinematographers (2022). American Cinematographer Manual (11th edn). Hollywood:CA: American Society of Cinematographers.

Ostenelli, Les (1982). Rough Guidelines on the Use of Super Techniscope. Courtesy of Rob Hummel.

Ostenelli, Les (1982). Super Techniscope Camera Specifications. Courtesy of Rob Hummel.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Rob Hummel’s career has revolved around cinematography, film labs, film formats, film restoration, preservation, animation, post-production, digital cinema, visual effects, and stereoscopic 3-D. He has been an Associate member of the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) since he was 32 and is a Life Fellow of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. He was the editor of the 8th edition (2002) of the American Cinematographer Manual and co-editor of the 11th edition (2022).

He started at Technicolor in 1979, working closely with filmmakers, where he oversaw dailies processing for all feature films and shepherded films in post-production up to answer print. He worked in post-production, animation and Imagineering at Walt Disney Studios, headed animation technology at DreamWorks and helped launch digital cinema units at Technicolor and Sony. During the 2006 restoration of Blade Runner, he single-handedly found the 65mm visual effects elements, which had been lost for over 20 years.

At Warner Bros. he oversaw digital restoration work on The Wizard of Oz, Casablanca and Gone With the Wind, among other titles. Hummel spearheaded tests and seminars on the pros and cons of different film formats.

He has served as chair and co-chair of the Public Programs Committee of the Academy’s Sci and Tech Council and served over 15 years on the Sci Tech Awards Committee. Rob has hosted several programs at the Academy on the history of Film Formats, Film Technology and 3D Stereoscopic Imaging, as well as given presentations in New York, London, Rome and Tokyo on the use of motion picture technologies in service of storytelling.

Joe Dunton, BSC, for clarifying the origins of his Super 35 format, and to the patient Technicolor technicians that shared their knowledge with me when this format was in its infancy: Joe Schmidt, Bud Castelli, Robert Buckley, Les Ostenelli, and Bob Crowdey.

Hummel, Rob (2024). “Super 35”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.