A 70mm, large-format negative to 35mm reduction, widescreen process.

Film Explorer

Although photographed on 70mm negative, Realife prints were made on 35mm film by optically reducing the image. The standard full-aperture frame was cropped at the top and bottom to maintain a widescreen image. The soundtrack was played back from a phonographic disc synchronized to the print.

Illustration by Christian Zavanaiu.

Identification

4.00mm x 12.00mm (0.945 in x 0.473 in).

Sources vary.

B/W, orthochromatic.

1

Unknown

Sound-on-disc.

48.77mm x 23.52mm (1.920 in x 0.926 in).

B/W, panchromatic.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

History

The Realife format was developed by the MGM Technical Department, in cooperation with the Loews Theater circuit (owned by MGM’s parent company), to address some of the constraints seen in the use of Fox’s Grandeur format. Grandeur used a 70mm negative and 70mm release print, with the primary goals of a larger image, a wider field-of-view in photography, a wide screen to better fill the stage in auditoriums and a sharper image with finer film grain. The main constraints were that it required a new film gauge and all-new equipment. Additionally, the projectors did not initially support 35mm projection, and in some cases, did not fit into already crowded projection booths.

MGM looked at the developments in widescreen being undertaken by the other studios and its Technical Department investigated what could be done to achieve most of the advantages of a widescreen format, but without the disadvantages of a larger film gauge for projection.

A promising approach had recently been the subject of an article in the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, which suggested that projected images with less visible film grain could be achieved by photographing on a larger negative and then using an optical reduction to a conventional 35mm film size (Powrie, 1924). This is because the film grain in a camera negative is typically large to increase its sensitivity to light, but the grain in a release print is smaller since a brighter printer lamp, or a longer exposure to the lamp, can be utilized.

Douglas Shearer of the MGM Technical Department led a study to investigate this possibility. They found that the average negative of 70 per cent density contained 25 silver clusters to each square thousandth of an inch (0.00064 square mm); but positive emulsion had four times as many clusters per unit area as this (Westerberg, 1930). Thus, by using a 70mm gauge during photography, many of the advantages of Grandeur could be retained, but by using an optical reduction to 35mm for release it avoided the most serious constraints for theaters. A reduced-height image, even if it was only half the height of a conventional full-silent frame, could still have a sharper and wider image with a more “immersive” scene when projected.

One area of contention during development was the aspect ratio as viewed in theaters. Many felt that the 2.00:1 aspect ratio of Grandeur was too wide, and that an aspect ratio of around 1.75:1 would be more appropriate (Weeks, 1930). Another issue was availability of wide-gauge cameras – most were either still in development or they were already on order to other companies.

Fortunately, a deal was reached with the Mitchell Camera Corporation to obtain some of the new 70mm model FC cameras. Serial numbers FC10 and FC12 were obtained on February 20, 1930, and FC11 and FC13 on March 31, 1930. A fifth camera, FC17, was later obtained on October 4, 1930 (Anon., 1988).

After testing the cameras and the quality of the reduction prints, MGM decided to use the technique on a feature film. The final decision on aspect ratio could be delayed and varying the cropping of the release print was still an option. Production began in the first week of April on Billy the Kid, starring John Mack Brown and directed by King Vidor (Variety, April 9, 1930).

An article describing the promising results of this approach appeared in the August issue of Motion Picture Projectionist (Finn, 1930) – the article doesn’t mention the producer, distributor, or exhibitor. However, another article published that month announced that MGM was using such an approach and was calling it “Realife” (Motion Picture News, August 23, 1930).

Frame images in the Motion Picture Projectionist article show an image cropped to an aspect ratio of about 1.75:1. The preference by MGM for this cropped image is also mentioned in a technical report written in July (Weeks, 1930). However, the decision was eventually made to retain the 2.00:1 aspect ratio for the release prints.

Following the filming of Billy the Kid, production began on MGM’s second Realife movie The Great Meadow in early September of the same year, and continued into November. John Mack Brown, who starred in Billy the Kid, also starred in The Great Meadow, although Charles Brabin was chosen as director. Although MGM indicated the possibility of six films being made in Realife, only one, Horse Flesh. was announced as starting production by November (Variety, November 12, 1930). Charles Brabin was also slated to direct this third Realife production. The movie was released in August 1931 under the new title Sporting Blood, but there is no confirmation that it was exhibited or even filmed for the Realife format.

Because of commercial concerns regarding competing widescreen formats and the added costs across the industry, a mandate was imposed by the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, acting through the Hayes office, limiting Realife presentations to ten theaters: Paramount Theatre, Detroit; Loews Capitol Theatre, New York City; Publix Oriental Theatre, Chicago; Loews Aldine, Pittsburgh; Fox Theatre, Atlanta; Loews Stillman Theatre, Cleveland; Loews State Theatre, Providence; Loews Midland Theatre, Kansas City; Loews Columbia Theatre, Washington DC; and Fox Criterion Theatre, Los Angeles (Motion Picture News, October 25, 1930). Billy the Kid opened in Realife in Detroit on October 16, 1930 with openings at the other theaters following on, shortly after that. The feedback from audiences after viewing Realife were mixed and proved disappointing to MGM. In December, 1930, the Hayes office further decreed that there would be no use of widescreen, or even enlarging projection lenses, for at least two years (Variety, December 17, 1930). Although The Great Meadow was apparently previewed in Realife to members of the press, it was seemingly released in March, 1931 in conventional 35mm format. Sporting Blood was released the same way in August, 1931 (Variety, November 12, 1930). Neither the 70mm master negatives, nor the 35mm reduction prints, are believed to still exist for the known Realife features.

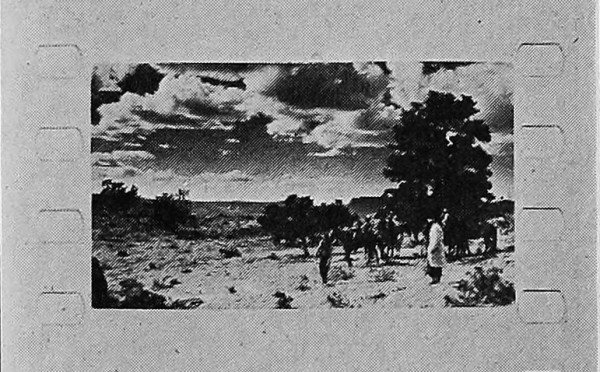

Frame sample from an article that shows an experimental trial of a Realife release print. The image size is estimated to be about 0.969 in x 0.555 in (24.61mm x 14.10mm). This scene does not appear in Billy the Kid.

Finn, James J., “Wide Film vs. Wide Image on Standard Film”. Motion Picture Projectionist, August, 1930: pp. 31–32.

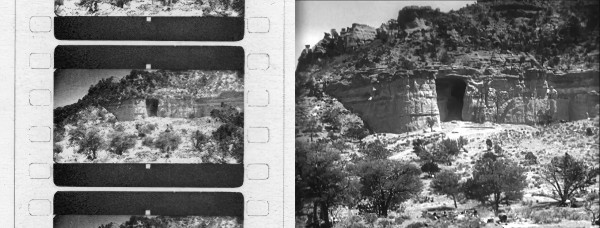

The 35 mm Realife reduction format (left) and the same scene from Billy the Kid filmed with a conventional 35mm camera (right). The small white squares (approximately 0.025 in (0.64mm) square) are believed to have been used to assist in framing during projection and would normally not be seen by the viewing audience.

Film Frame Collection (P-074), Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Frame grab from Billy the Kid (King Vidor, 1930), DVD (Burbank, CA: Warner Archive, 2009).

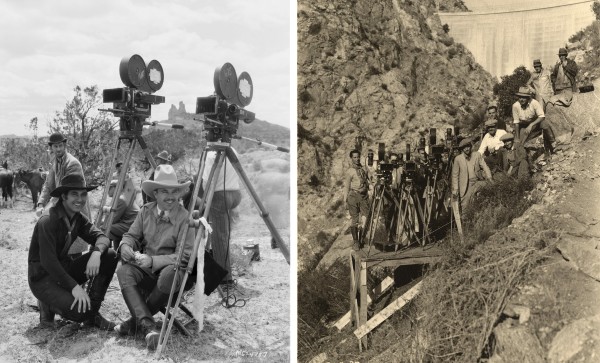

Left: The 70mm Mitchell FC camera (left) and 35mm Mitchell Standard camera (right), during the production of Billy the Kid. Beneath the cameras are star John Mack Brown (dark attire) and director King Vidor.

Right: Two pairs of 70mm Mitchell FC and 35mm Mitchell Standard cameras during the production of The Great Meadow.

Dan Sherlock collection; Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills, CA, United States.

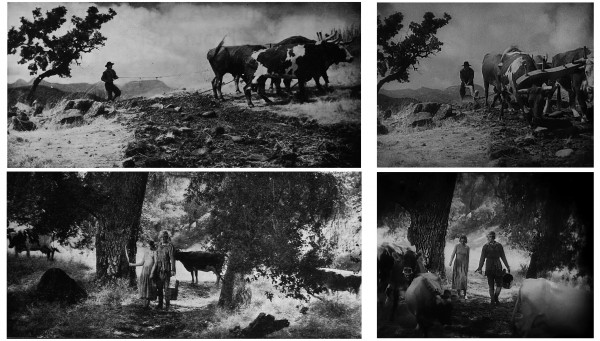

Images as they would have been seen, from the Realife version of The Great Meadow (left); and from the conventional 35 mm version (right).

New Movie Magazine, January, 1931: pp. 98–99; Frame grabs from The Great Meadow (Charles Brabin, 1931), DVD (Burbank, CA: Warner Archive, 2018).

Selected Filmography

Feature filmed simultaneously in 70mm and conventional 35mm. Realife version released in ten cities.

Feature filmed simultaneously in 70mm and conventional 35mm. Realife version released in ten cities.

Feature, filmed simultaneously in 70mm and conventional 35mm. Some members of the press appear to have viewed the Realife version prior to release, but apparently only the conventional 35mm version was eventually released.

Feature, filmed simultaneously in 70mm and conventional 35mm. Some members of the press appear to have viewed the Realife version prior to release, but apparently only the conventional 35mm version was eventually released.

Technology

Realife used the same 70mm cameras that were used for Fox’s Grandeur format. That format used a new camera design from Mitchell known as the model FC (for “Fox Camera”) which was basically a scaled-up version of the commonly used Mitchell Standard. The camera aperture of the model FC has been quoted with contradictory dimensions from various sources, so it is difficult to precisely determine the exact values. According to a Mitchell Camera Co. dimensional drawing dated March, 1930, the camera aperture size was 1.920 in x 0.926 in (48.77mm x 23.52mm) (Mitchell Camera Corp., March 27, 1930). No published specification has been found for the reduction image size on the 35mm release print, but scaling the image from frame samples gives an estimated dimension of 0.980 in x 0.490 in (24.90mm x 12.45mm). The implied maximum projectable area, from an article published after the release of Billy the Kid. (Motion Picture News, October 25, 1930) was 0.945 in x 0.473 in (24.00mm x 12.01mm). Since Realife was designed to be shown at 24 fps on conventional 35mm projectors, MGM changed to this frame rate from Grandeur’s 19 fps, which had been used up until early 1930.

Mitchell offered the following lenses for the 70mm FC camera: Astro Pan-Tachar 50mm at f/2.0; and 75mm, 100mm and 150mm lenses at f/2.3 (International Photographer, July 1930). In addition, Cooke offered Speed-Panchro lenses at 47mm, 58mm and 75mm and 100mm at f.2. (International Photographer, November, 1930)

Apart from the larger, wider screen, the main differences in projection were the use of an aperture plated filed to the appropriate size for Realife, and a strongly recommended higher-quality Bausch & Lomb Super-Cinephor lens to provide for the larger image area. For theaters with very large screens, it was also recommended to use cylindrical condenser lenses in the lamphouse to compress more of the light path onto the rectangular image area.

To achieve the maximum image area on the 35mm Realife prints, the image extended the full width of the silent aperture which left no room for an optical soundtrack. The soundtrack was played back from a synchronized audio disc.

References

Anon. (“L.R.”) (1988). “Mitchell Serial Number Sales Dates”. Unpublished internal document, dated 1988. Dan Sherlock collection.

Bell & Howell Corp. (1930). “Announcing New Cooke Speed-Panchro Lenses”. International Photographer, November: p. 3.

Finn, James J. (1930). “Wide Film vs. Wide Image on Standard Film”. Motion Picture Projectionist, August: pp. 31–32.

Mitchell Camera Corp. (1930a). “70mm Film”. Dimension drawing dated March 27. Mitchell Camera Corporation Collection/Joe Dunton, Wilmington, NC, United States.

Mitchell Camera Corp. (1930b). “Mitchell Wide Film Camera Price List,” International Photographer, July: p. 35.

Motion Picture News (1930a). “M-G-M Launches “Realife” Wide Film Process”. Motion Picture News, August 23: p. 25.

Motion Picture News (1930b). “In 12 Cities”. Motion Picture News, October 25: p. 31.

Powrie, J. H. (1924). “Reducing the Appearance of Graininess of the Motion Picture Screen Image”. Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, September: pp. 49–57.

Tower Magazines, Inc. (1930). “’The Great Meadow’ Scenes”. New Movie Magazine, January: pp. 98–99.

Variety Publishing Company (1930a). “Haphazard Ways of Starting on New Wide Film in Coast Colony”. Variety, April 9: p. 11.

Variety Publishing Company (1930b). “Six in Realife on Current M-G List”. Variety, November 12: p. 4.

Variety Publishing Company (1930c). “Wide Film is Ruled Out”. Variety, December 17: p. 5.

Weeks, H. Keith (1930). “Wide Film Activities”, July 18, 1930. Earl I. Sponable papers, Box 10, Grandeur folder, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library, New York, NY, United States.

Westerberg, Fred (1930). “Symposium on Wide Film Proportions”. Motion Picture Projectionist, November: p. 20.

Patents

Olindo O. Ceccarini (Assignee: MGM) 1930. Optical system for photographic purposes. US Patent 1,938,808, filed December 15 1930; issued December 12 1933.

Coors, Fritz Jr. 1931. Method for Producing Motion Picture Film. US Patent 1,905,442, filed June 2, 1931, and issued April 25, 1933.

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Dan Sherlock earned his Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering from the California State University Long Beach. He was then with Hughes Aircraft / Hughes Training for 16 years, and helped design flight and driving simulators, specialized military, industrial and commercial displays, computer-based training, and producing videos and analysis for accident reconstruction. This was followed by working as a project engineer to finalize the design and perform rigorous testing and delivery of an atmospheric controller for the International Space Station. Following project completion, he then worked for Rockwell Collins passenger systems where he led in the development of in-flight video displays and equipment, and earned three US patents for these designs. He then joined the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Science and Technology Council as Sr. Project Engineer. During his 16 years with the group, his responsibilities included being lead in the acquisition, identifying and cataloging of the film negatives from the Showscan Corporation, development of a method of better matching luminaire spectra which became the Academy’s Spectral Similarity Index (SSI) which was published as SMPTE ST 2122:2020, and he was the lead designer and principal author of the SMPTE Digital Leader which was published as SMPTE RP 428-6:2009. He has spent most of his life studying the history and details of media technology and continues to contribute to written and web articles on the subject.

Sherlock, Dan (2024). “Realife”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.