17 pre-tinted film stocks developed by Loyd A. Jones of the Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories for use on sound films.

Film Explorer

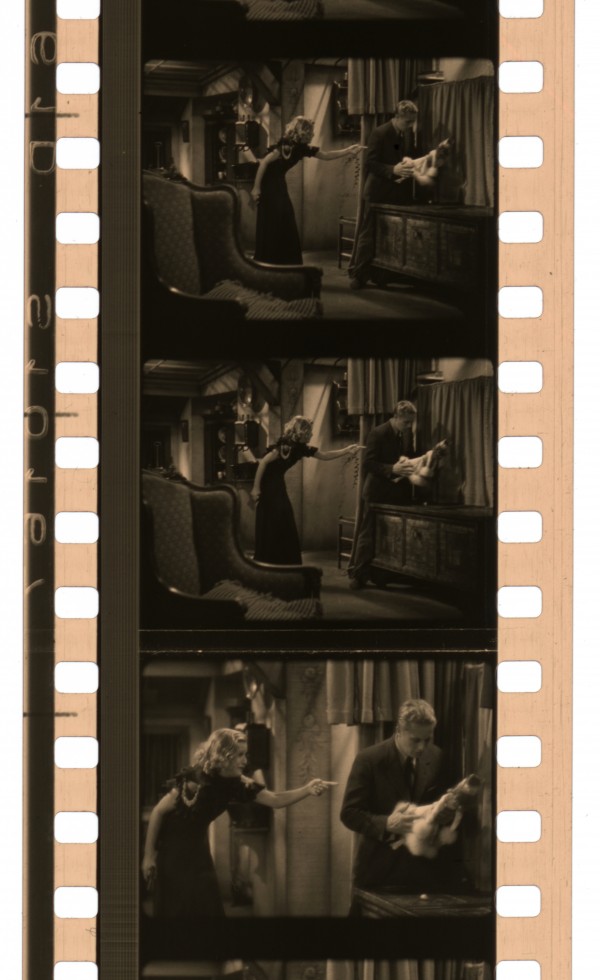

Example of an “Afterglow” Sonochrome tint in I Am Suzanne! (1934). The film also had sequences printed on “Rose Doree” and “Sunshine”.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

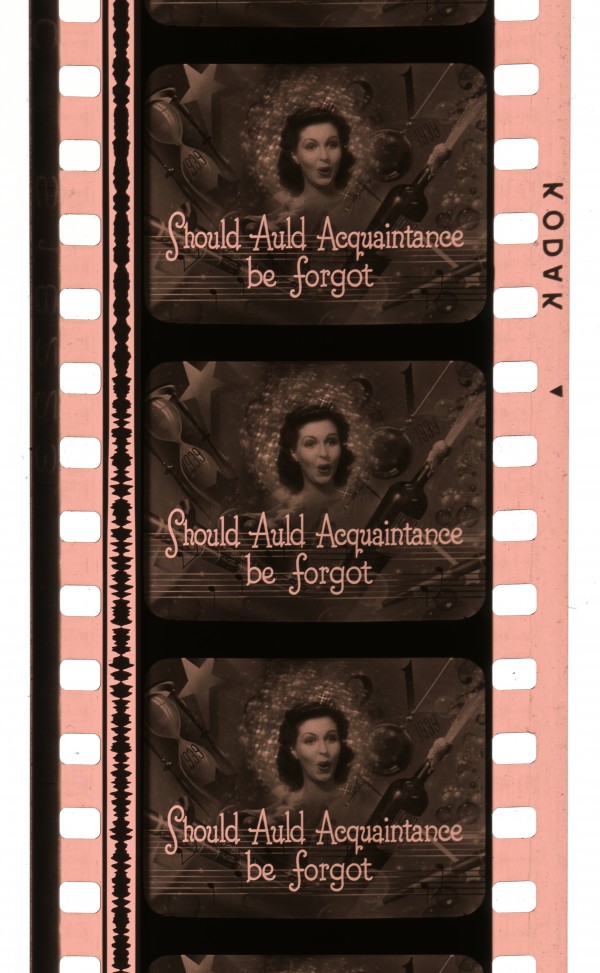

A 1938 seasonal snipe, featuring Ann Miller, printed on “Rose Doree” stock.

Jack Theakston, New York, NY, United States.

“Verdante” was used for the storm sequence in Portrait of Jennie (1948).

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Identification

B/W emulsion on a tinted base.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

1

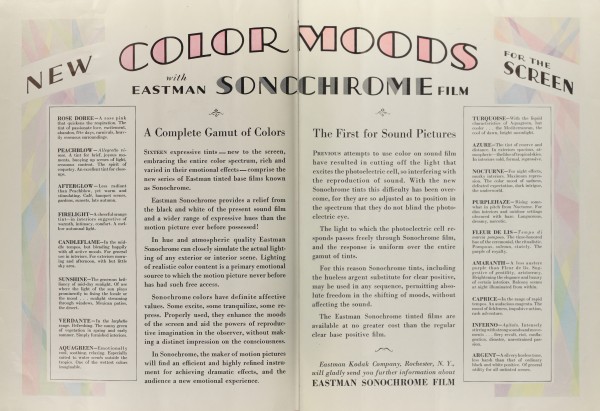

The following colors were available: Rose Doree (deep warm pink); Peachblow (delicate flesh pink); Afterglow (soft rich orange); Firelight (soft yellow-orange); Candleflame (pastel orange-yellow); Sunshine (yellow); Verdante (pure green); Aquagreen (brilliant blue-green); Turquoise (brilliant blue); Azure (strong sky-blue); Nocturne (deep violet-blue); Purplehaze (lavender); Fleur De Lis (rich royal purple); Amaranth (warm purple); Caprice (cool pink); Inferno (fiery red); Argent (silvery hueless tone)

None

Prints on Sonochrome stock could have either variable-density, or variable-area soundtracks.

History

The introduction of synchronized sound in the late 1920s added a new dimension to the movies. Filmmakers quickly realized that the dyes used for tinting film, a technique used in motion pictures almost from inception, absorbed light from the optical soundtrack, which compromised audio playback. Eastman Kodak Research Laboratory team adapted their existing pre-tinted stocks under the direction of Dr. Loyd A. Jones, to overcome the obstacle of combining color tinted film and an optical soundtrack. A Science Service Associated Press article (May 9, 1929) announced the introduction of this new stock:

Tinted motion picture films, with red for fire scenes, blue for night scenes, green for forest scenes or yellow where artificial light is represented, will now return to theatres, from which they were forced for technical reasons with the advent of talkies.

This is made possible with a new series of films announced this morning at the meeting of The Society of Motion Picture Engineers at the Bell Laboratories here.

Sixteen separate tints have now been developed running the entire range of the spectrum. The peculiar thing about these new colors, however, is that while they are blue, green, yellow, etc. to the eye, each of them contain some blue-violet as well, and so transmits the color required for the photoelectric cell. According to Dr. Jones, the use of these tints will aid the movies in arousing the desired emotional moods of the audience.

Even before the SMPE meeting in May of 1929, it seems that Sonochrome stock was already in use. Fox Film Corp.’s first all-talking Movietone feature film, In Old Arizona (1928), featured several sequences on “Purplehaze” lavender-tinted stock. In April 1929, Pathé released the Morton Downey musical vehicle Mother’s Boy, which may possibly be the first film released entirely on Sonochrome stock. Mother’s Boy opened in New York City the same day as the SMPE meeting. Richard Mason’s review of the film in the Brooklyn Standard Union, May 11, 1929, mentions Sonochrome’s tints:

The producers of ‘Mother’s Boy’ at the George M. Cohan Theatre have never mentioned it, but unless these old eyes deceive, Morton Downey’s musical travail is the first to be recorded on tinted ‘all-over’ film.

It is, apparently, the latest Eastman wonder over which members of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers bent their heads in admiration on Tuesday. By sixteen tints the engineers were told, the hearts of cinema customers will be wrung, jostled or broken twice as easily as with plain white.

In ‘Mother’s Boy’ the tints are used on that theory. When Morton’s heart glows, so does his face, with the mild and pleasant ‘Candleflame’ or perhaps it is ‘Sunshine’. When Morton’s mother lies near death, her wan face is bathed in turquoise, coolish, but not so cold as Azure or Nocturne, for she is going to recover later.

The colors in ‘Mother’s Boy’ are almost unnoticeable, consequently they won’t worry you whether you like them or not.

Sonochrome’s advertising played up the psychological effect of the colors on moviegoers, such as “Aquagreen” being “emotionally cool, soothing, relaxing”, while “Caprice” was “the mood of fickleness, impulsive action, rash adventure”. The marketing campaign also used fanciful names for the tints, such as “Rose Doree”, “Verdante” and “Fleur De Lis”, in place of pink, green and purple. Mason hints at the emotional impact the different colors could have on the audience in his review of Mother’s Boy. But it is the last sentence of the review which may give us the biggest clue as to why the use of Sonochrome went mostly unnoticed at the time and is so little remembered today. Some Sonochrome stocks, like Verdante, were quite strong and vivid on the screen, while some of the more pastel colors appeared pale to the point of invisibility, especially if the throw from the projection booth to the screen was long.

In the early 1930’s Fox and Paramount produced a number of films, both features and shorts, on Sonochrome stock; other studios, such as Tiffany, Warner Bros. and RKO, used Sonochrome – but, to a lesser extent. Films were released with an isoloated Sonochrome sequence (or, a number of sequences), such as Warner Bros.’s The Crowd Roars (1932), which used Sonochrome “Inferno” to add visual excitement to a sequence. And some films were printed entirely on Sonochrome stock, like Sign of the Cross (Cecil B. DeMille, 1932), which employed “Candleflame” for the entire print. Occasionally a film might use more than one color per reel, as was done with RKO’s Bird of Paradise (King Vidor, 1932), where reels 2 and 3 used both Firelight and Verdante, with the change of stock coming mid-reel. By “blooping” the sound track at the splice, the pop the audience would hear could be minimized. All the other reels were printed on a single Sonochrome tint for their entirety.

An unexpected use for Sonochrome arose in the late 1930s, when John Nickolaus, head of the MGM laboratory at Culver City, devised a new way to chemically tone B/W prints. The Good Earth (Sidney Franklin, 1937) was the first film released using this new sepia-tone process. But by the end of 1937, Nickolaus was applying his new toning technique to Sonochrome stock, thus achieving two- and, even, three-color effects. The September 1937 issue of American Cinematographer featured a lengthy article on the sepia-platinum process and went into detail about the use of it in The Firefly (Robert Z. Leonard, 1937):

Effects of Infinite Variety – Multiple tones and multiple tone-and-tint combinations allow infinitely varied effects in which the highlights are one color, the halftones another, and the shadows yet a third color.

The most recent example of this technique, “The Firefly”, made extensive use of such combinations as sepia-pink; sepia-orange; sepia-blue-pink, etc. Certain romantic night exteriors, for instance, made extensive use of the latter combination and produced night effects which absolutely could not be approached in ordinary black-and-white.

Use of Sonochrome fell off sharply during the 1940s, and by the mid-1950s, through the 1960s, seemed to be mainly used for theatrical snipes (material projected before the feature presentation, other than trailers). In his 2009 Film History article, “‘Unnatural Colors’: An Introduction to colouring techniques in silent era movies”, Paul Read wrote that Sonochrome, as a product, was considered a marketing disaster. But Sonochrome was not quite the disaster it has been made out to be. Over 200 hundred films, features and shorts, used Sonochrome stocks from late 1928, through the 1960s. While the majority of feature films printed on Sonochrome were released between 1930 and 1933, Kodak continued to manufacture the stock until 1970. In addition, Eastman Kodak was not the only company producing pre-tinted positive stock for sound films: DuPont, Agfa, Gevaert and Fuji all manufactured pre-tinted stocks during the early sound era, to rival Sonochrome positive film.

Sonochrome two-page trade advertisement.

Anon. (1929). “New Color Moods for the Screen”. Film Daily (June 30): pp. 8–9.

A color wheel of the Sonochrome tints, from a promotional booklet distributed by Eastman Kodak.

Stills, Posters and Paper Collections, Moving Image Department, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Examples of pre-tinted sound film stocks from (left to right) DuPont, Gevaert and Fuji.

Jack Theakston, New York, NY, United States.

Selected Filmography

The entire film was printed on various Sonochrome stocks: Candleflame, Firelight, Verdante, and Peachblow.

The entire film was printed on various Sonochrome stocks: Candleflame, Firelight, Verdante, and Peachblow.

Verdante swamp sequence in a B/W feature.

Verdante swamp sequence in a B/W feature.

The entire film was printed on Verdante stock.

The entire film was printed on Verdante stock.

Nocturne jungle sequence in a B/W feature film.

Nocturne jungle sequence in a B/W feature film.

Entire film printed on various Sonochrome stocks: Afterglow, Rose Doree and Sunshine.

Entire film printed on various Sonochrome stocks: Afterglow, Rose Doree and Sunshine.

Fleur De Lis Sonochrome sequences in a B/W feature film. One of the earliest documented Sonochrome releases.

Fleur De Lis Sonochrome sequences in a B/W feature film. One of the earliest documented Sonochrome releases.

The entire film was printed on various Sonochrome stocks.

The entire film was printed on various Sonochrome stocks.

Sonochrome nighttime sequences used Purple Haze, for exteriors, and Candleflame for interiors.

Sonochrome nighttime sequences used Purple Haze, for exteriors, and Candleflame for interiors.

Storm sequence on Verdante Sonochrome stock – with a sepia-toned sequence and a Technicolor insert elsewhere in the film.

Storm sequence on Verdante Sonochrome stock – with a sepia-toned sequence and a Technicolor insert elsewhere in the film.

Entire film on Candleflame stock.

Entire film on Candleflame stock.

Nocturne Sonochrome sequences.

Nocturne Sonochrome sequences.

Technology

Use of tinting in motion pictures reached its peak in the late 1910s and early 1920s. At that time Eastman Kodak offered an alternative to dye tinting: a pre-tinted film base. Kodak introduced nine pre-tinted bases in 1921– both Agfa and DuPont began producing their own pre-tinted stocks soon after. Following the introduction of optical soundtracks in the late 1920s, it was discovered that the dyes on tinted stock compromised the quality of audio reproduction. Although the audio quality of variable-density soundtracks was compromised to a greater degree than with variable-area tracks, both suffered distortion as a result of diminished light reaching the projector’s soundhead. This issue was resolved with the introduction of Sonochrome pre-tinted stocks in 1929. As with all pre-tinted stocks, the dyes were impregnated into the base, giving a uniform color intensity throughout the frame, unlike films tinted in a dye bath, where the dye was applied to the gelatin emulsion layer. As reported in the Evening Courier, the issue of lower light transmission by the base-layer tints was overcome when,

engineers discovered that through various combinations of colors, the light of one color always penetrated. This was blue-violet, the color to which the photo-electric cell is most sensitive. So the experimenters developed a film in which the tints were compounded with just enough blue-violet in it to transmit the rays necessary for sound reproduction (Anon., 1929).

Standard orthochromatic emulsion was applied to the pre-tinted base. Sonochrome used a cellulose nitrate base, until the discontinuation of nitrate film in 1951. After 1951, triacetate base was used, until Sonochrome was discontinued around 1970.

Magnified cross-section of a pre-tinted film print. The B/W emulsion layer containing the image is on the top of the base. The blue tint was applied directly to the underside of the cellulose nitrate, or triacetate base.

Courtesy of George Eastman Museum & Image Permanence Institute, Rochester, NY, United States.

References

Anon. (1929). “Talking Pictures in Colors Developed by Movie Experts”. Evening Courier, May 8, 1929: p. 7.

Anon. (1937). “M-G-M to Make Wide Use of Tone-Tint Merging”. American Cinematographer, 18:9 (September): p. 373.

Jones, Loyd A. (1929). “The Emotional Appeal of Color”. American Cinematographer, 10:5 (August): pp. 5–6, 36, 38.

Mason, Richard (1929). “The New Films – Scientists Devise a Way to Make Villains Blush”. Brooklyn Standard Union, May 11, 1929: p. 12.

Read, Paul (2009). “‘Unnatural Colors’: An Introduction to colouring techniques in silent era movies”. Film History, 21:1: p. 23

Patents

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Anthony L’Abbate is Preservation Manager in the Moving Image Department at the George Eastman Museum. He graduated from The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation in 1999. L’Abbate was employed as a laboratory technician at Cinema Arts, Inc., Newfoundland, PA, from 1999 to 2001. He returned to the Eastman Museum in 2001, as their Stills Archivist. He moved over to preservation in 2007, as Preservation Officer, and was promoted to Manager in 2017. During his five-year tenure as Stills Archivist, he supervised the scanning of hundreds of still images and frame captures from preserved films. He has overseen the preservation and restoration of Roaring Rails (1924), Jazzmania (1923), Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951) and Huckleberry Finn (1920). Recent restoration projects include The Clutch of Circumstance (1918) and the reconstruction of The Unknown (1927).

L’Abbate, Anthony (2024). “Sonochrome”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.