A camera and projector for taking a short sequence of pictures on roll film.

Film Explorer

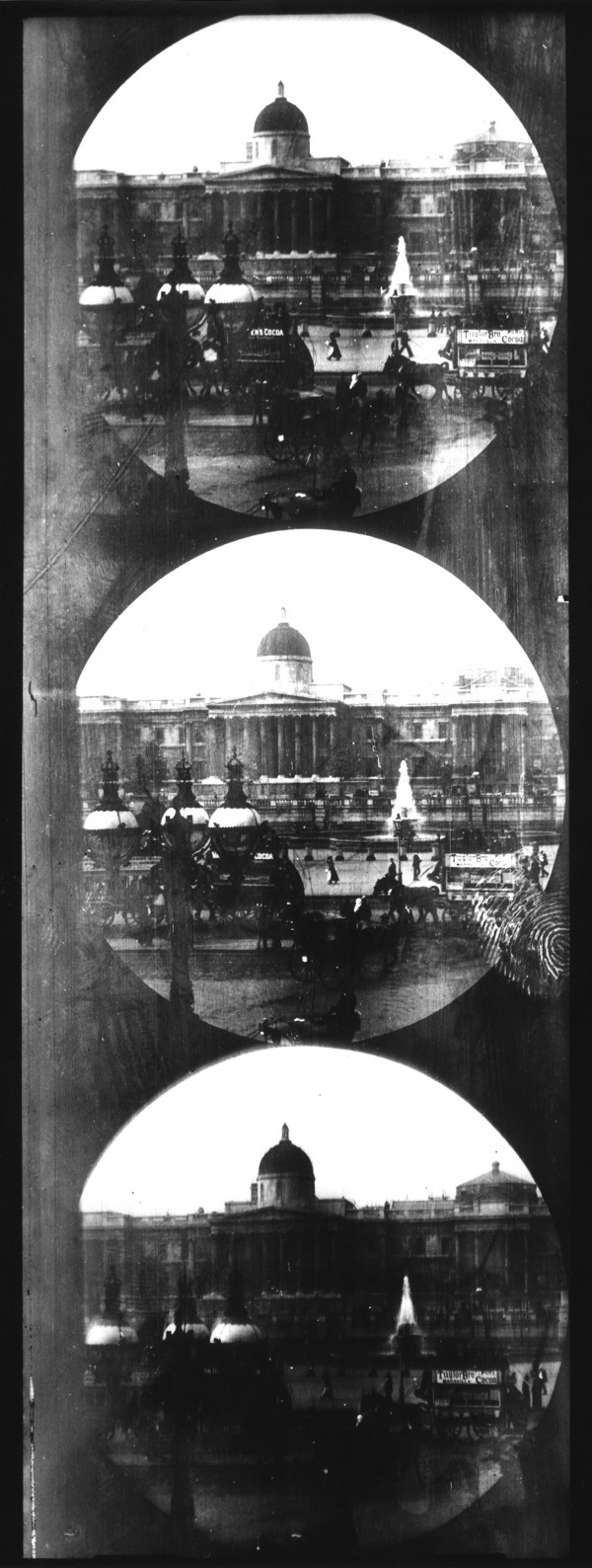

Three of the ten surviving frames photographed with the Kinesigraph camera, showing traffic in London’s Trafalgar Square, 1890.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

Identification

circular, 64mm (2.52 in) in diameter.

circular image.

One frame at a time. The film ran continuously on a sliding “back-and-forth” transport mechanism behind the lens – the upwards movement of the mechanism matched the downwards movement of the film, rendering it effectively stationary at the lens axis, for each frame projected.

Initially Kodak stripping roll film with the paper backing made transparent by soaking in hot castor oil. Later standard B/W emulsion, on celluloid support.

1

circular, 64mm (2.52 in) in diameter.

One frame at a time. The film ran continuously on a sliding “back-and-forth” transport mechanism behind the lens – the upwards movement of the mechanism matched the downwards movement of the film, rendering it effectively stationary at the camera lens axis, to record each frame.

Initially Kodak stripping roll film (intended for still photography, whereby the photographic emulsion was removed from its paper backing for intended printing onto photographic paper), B/W. Later standard B/W emulsion, on celluloid support.

History

Wordsworth Donisthorpe (1847–1914) and his cousin Willliam Carr Crofts (1846–94), educated respectively at Cambridge University and Oxford University, patented a moving picture camera and projector in 1889, from which ten frames survive, of traffic in Trafalgar Square, London. Donisthorpe, the prime mover in their experiments, was the son of an inventor and manufacturer of wool-combing machinery from Leeds, in Yorkshire, who was also a prominent chess player and a political philosopher. He had taken tentative steps towards making photographic moving pictures as early as November 1876, taking out a provisional UK patent on an apparatus he called the Kinesigraph – the images were first recorded on a series of glass plates, then transferred to, and then viewed, as prints on a strip of paper wound between two cylinders. But this provisional patent was never followed up and apart from a January 1878 proposal in a letter to the journal Nature, suggesting the linking of his system of moving images to the recently announced Edison phonograph, there was no known further progression of this idea.

By 1882, Donisthorpe and Crofts were associated as founder members of the Liberty and Property Defence League, a lobby group that emerged in response to the rise of trade unionism and socialism, which set out to promote Individualism and laissez-faire economics. After six years of speeches and pamphleteering, they began work in late 1888 on a new moving picture apparatus that might be used in support of their political interests – still called a Kinesigraph, but now using Kodak stripping film with its paper backing, as produced for the newly launched Kodak still-image camera. A UK patent for the new device was applied for on August 15, 1889, and, in 1890, Donisthorpe and Crofts set up their apparatus in empty rooms (formerly occupied by the International Club, above shops at 1–4 Charing Cross Road) overlooking Trafalgar Square, in London. They produced a short strip of film showing street traffic in the square. Seeking funding for the moving picture experiment, Donisthorpe turned to the publisher George Newnes, a fellow vice-president of the British Chess Club, who then appointed two “experts” to evaluate the prospects for the invention – one a painter, the other a magic lantern maker. In the opinion of both men, the idea was without merit. As a result, no funding was forthcoming from Newnes, or his circle of contacts.

At this time, short-exposure photography was at a technological turning point. Although Eadweard Muybridge had been capturing movement for over a decade, at the start of the 1890s, several independently conceived systems for projecting moving images were beginning to emerge. Significantly, Augustin Louis Aimé Le Prince (1841–90?), also based in Leeds, was working on his own moving picture apparatus – he succeeded in producing some lengths of film – a few of which have survived to the present day, as copies. They would soon be joined by William Friese-Greene (1855–1921), who was experimenting with moving picture apparatus of his own. And, of course, in the United States, Thomas Edison (aided by William Kennedy Laurie Dickson) was beginning his development of the Kinetoscope.

Donisthorpe might have considered himself unlucky to have had his work evaluated by two “experts” who one presumes were completely out of touch with the photographic developments of the day. Without funding, development of the Kinesigraph apparatus ground to a halt. Athough patents stated that the Kinesigraph could be used for projection, this function of the machine was never properly resolved, and no exhibitions (either public, or private) are recorded.

The Kinesigraph was chosen as one of the 14 working reproductions of early motion picture cameras constructed by The Race to Cinema project (a team of specialists in film and photography, headed by Gordon Trewinnard) in 2000.

Selected Filmography

Ten frames survive.

Ten frames survive.

Technology

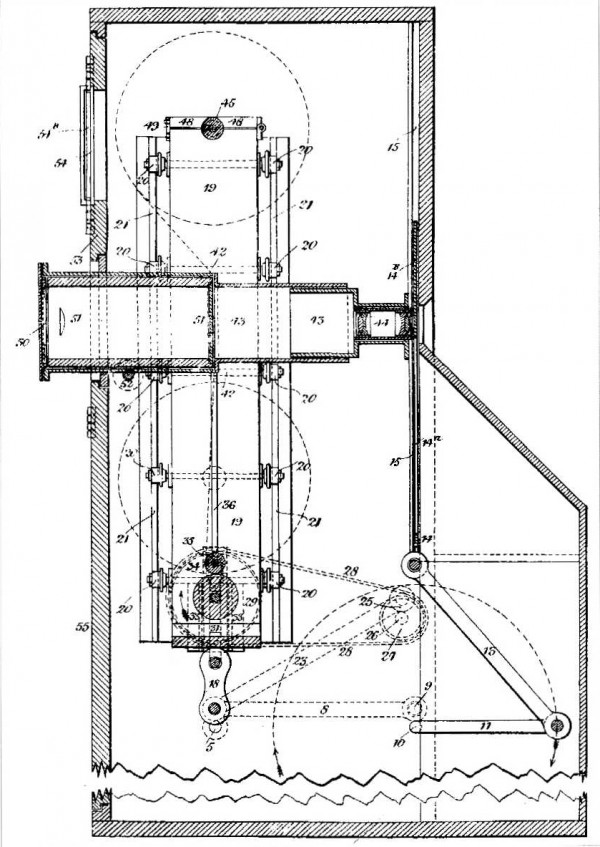

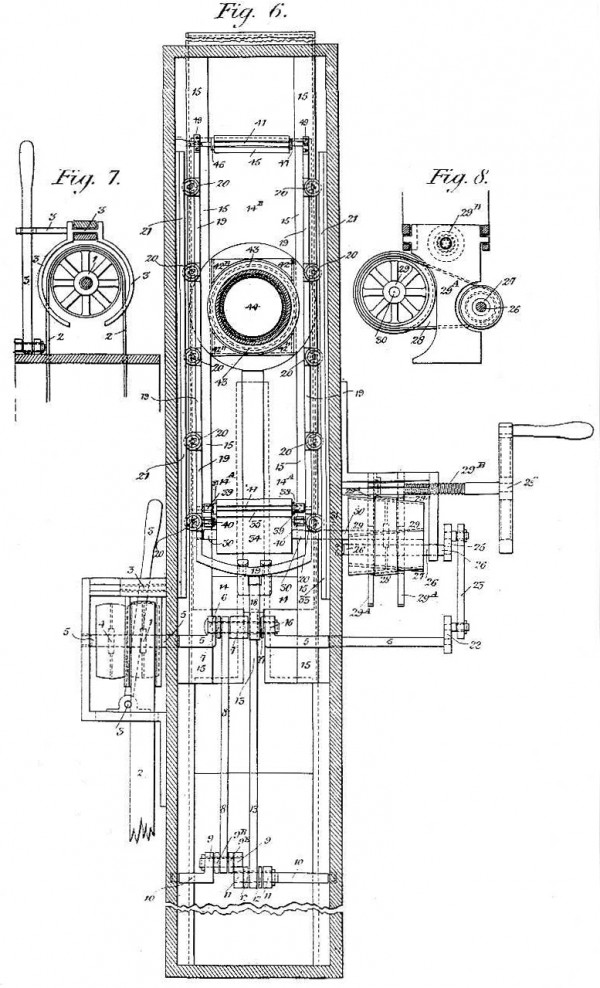

The Kinesigraph of Wordsworth Donisthorpe and William Carr Crofts was an unusual apparatus – correct in its photographic theory and derived, in part, from the wool-combing machinery invented and manufactured by Donisthorpe’s father. The convertible camera-projector stood on the floor and its mechanisms were controlled by means of a long floor-mounted lever – similar in fashion to many factory machines of the day.

Heavy and awkward, it sat on top of an iron base and measured 20 in x 23 in by 10 in (50.8cm x 58.4cm x 25.4cm). The mechanism was driven by a wide foot treadle, which was connected, at floor-level, to the machine by an iron crankshaft. The Kinesigraph works ran continuously: a double-motion was employed, whereby the 3.25-in (83mm) film ran downwards, from a top roll to a lower roll, while the entire film-carrying element shuttled up and down, in synchrony, behind the camera lens. The upward movement of the carriage mechanism, cancelled out the continuous downward journey of the film – meaning that the film was momentarily held steady in relation to the lens axis, enabling a clear image to be recorded on the photographic emulsion. This was a unique solution, bearing resemblance to some industrial machinery of the time, including the wool-combing machines invented and manufactured by Donisthorpe’s father (Herbert, 2017: p. 74).

In the proposed projector, a kerosene lamp provided illumination (later iterations suggested a limelight burner), but both the insubstantial substrate (gelatine stripping skin, or paper backing soaked in hot castor oil, later celluloid) and the lack of perforations resisted projection and no refinement seemed to make it practicable. In operation, the machine was very loud, described as “like a young threshing machine or a small gas-engine, or, perhaps, a little of both.” (Photographic Life, 1897)

Side view of the Kinesigraph – from the British patent.

Wordsworth Donisthorpe & William Carr Crofts, Improvements in the Production and Representation of Instantaneous Photographic Pictures. UK patent 12,921, filed August 15, 1889, and issued November 15, 1890.

Front view of the Kinesigraph from the British patent. Fig. 6 shows the camera; Fig. 7 a detail of the clutch that engages the works; and Fig. 8 a drive belt connecting the framing adjustment cones (for making very fine adjustments to the aperture placement).

Wordsworth Donisthorpe & William Carr Crofts, Improvements in the Production and Representation of Instantaneous Photographic Pictures. UK patent 12,921, filed August 15, 1889, and issued November 15, 1890.

References

Photographic Life (2017). “The Cinematograph in 1889 – An interview” (from Photographic Life, 17 February 1897). In Herbert, Stephen, Industry, Liberty, and a Vision, pp. 77 & 194n3.

Coe, Brian (1981). The History of Movie Photography. Westfield, NJ: Eastview Editions.

Herbert, Stephen (2017). Industry, Liberty, and a Vision. Wordsworth Donisthorpe’s Kinesigraph (2nd edn). Hastings, East Sussex: The Projection Box.

Herbert, Stephen & Luke McKernan (1996). Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema. London: BFI Publishing.

“Donisthorpe/Crofts Kinesigraph Camera”. The Race to Cinema. https://web.archive.org/web/20240221155015/http://www.theracetocinema.com/cameras/donnisthorpe-croft/ (accessed December 13, 2024).

Shah, Irfan (2024). “Sensitive Material: Wordsworth Donisthorpe, Blackmail, and the First Motion Pictures”. The Public Domain Review (June 26). https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/wordsworth-donisthorpe-blackmail-and-the-first-motion-pictures/ (accessed December 11, 2024).

Patents

Wordsworth Donisthorpe & William Carr Crofts. Improvements in the Production and Representation of Instantaneous Photographic Pictures. UK patent 12,921, filed August 15, 1889, and issued November 15, 1890.

Wordsworth Donisthorpe & William Carr Crofts. Perfectionnements dans la production et la répresentation des images photographiques instantées. French patent 209,174, filed October 28, 1890.

Wordsworth Donisthorpe & William Carr Crofts. Vorrichtung zur Erzeugung und Vorführung von Augenblicksbildern. German patent 58,166, filed November 9, 1890, and issued August 11, 1891.

Wordsworth Donisthorpe & William Carr Crofts. Method of Producing Instantaneous Photographs US patent 452,966, filed November 11, 1890, and issued May 26, 1891. https://patents.google.com/patent/US452966A/

Compare

Related entries

Author

A student of David Shepard and James Card in the 1960s, Deac Rossell is an active independent historian of early cinema, magic lantern culture and chronophotography. Now retired from Goldsmith’s College, University of London, he has published five books – most recently Chronology of the Birth of Cinema 1833–1896 (2022) – and contributes frequently to encyclopedias, anthologies, exhibition catalogues and academic journals. He was the Curator of the Ottomar Anschütz exhibition seen at the Düsseldorf Filmmuseum and the Deutsches Filmmuseum, Frankfurt, in 2000 and 2001. His most recent book, Finding Birt Acres. The Rediscovery of a Film Pioneer, written with Barry Anthony and Peter Domankiewicz, will be published in 2025.

Stephen Herbert; and for advice and guidance, James Layton and Crystal Kui.

Rossell, Deac (2024). “Kinesigraph”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.