Film Explorer

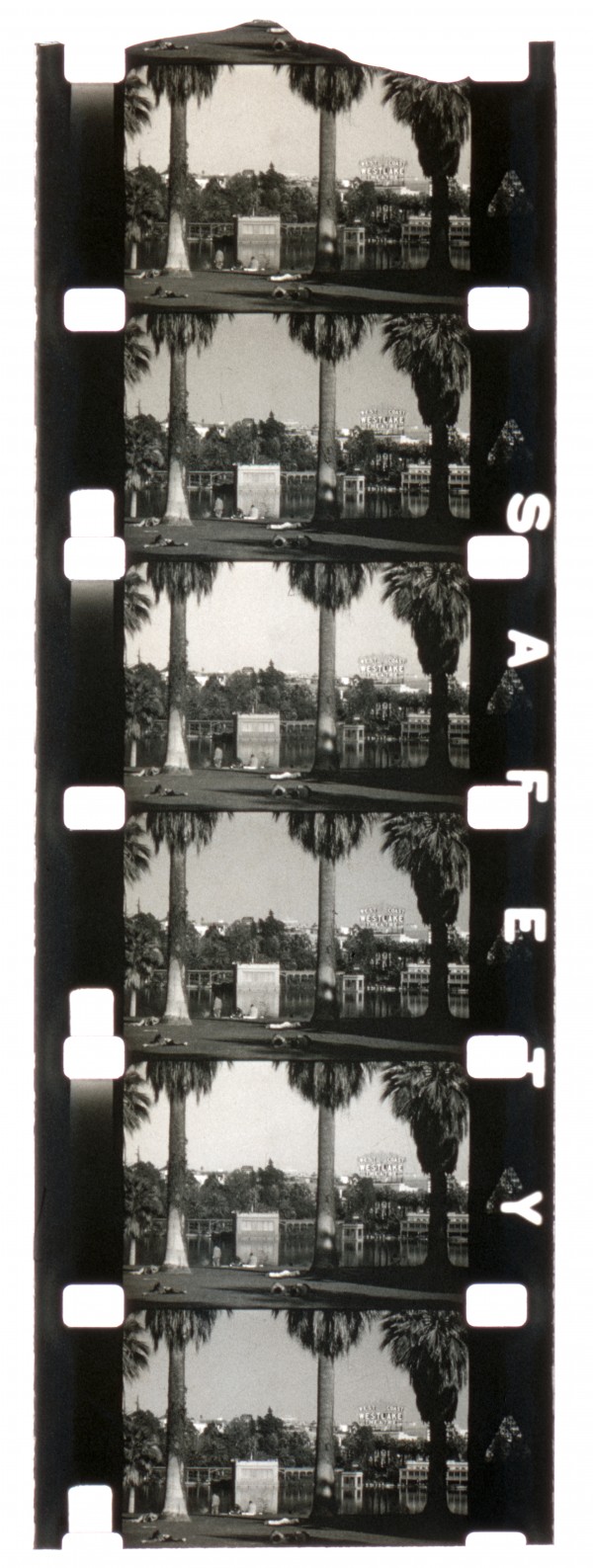

Unidentified 16mm B/W reversal film frames, c. 1932. Note the tonal difference between frames due to the alternating red and green filters. Also visible on the right side of this frame sample between the perforations is the Kodak edge code for 1932 (square, cross) and the camera identification mark (an upward pointing triangle central to the film frame) which indicates this film was shot using a Bell & Howell Filmo 70. The white rectangular marks above alternate perforations on the left edge indicate the frames exposed through the green filter. This is the only known surviving example of Morgana.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, California, United States.

Identification

History

Morgana was a two-color additive process developed by Lady Juliet Rhys Williams and Sydney George Short in the UK, based on the same rotating filter principle as Kinemacolor. Lady Juliet, a politician and advocate for social reform in south Wales, had a strong interest in motion pictures and a familial connection to the industry through her mother, Elinor Glyn, the writer-screenwriter-director-producer. Glyn’s company, in which Lady Juliet, her husband – Lord Rhys Rhys Williams – and Glyn’s other daughter – Lady Margot Davson – were involved, had been a significant investor in Talkicolor: another (commercially unsuccessful) two-color additive process. Lady Juliet’s interest in color motion picture film was first piqued in 1924 when visiting the set of Glyn’s production of His Hour.

Several years later, on the set of Glyn’s Knowing Men (1930), recognizing the many technical problems with Talkicolor, Lady Juliet was inspired to explore perfecting the two-color rotating filter process for the amateur market. Working with S. George Short in London, their experiments at first used 35mm but soon shifted to 16mm and the amateur market. To overcome the distracting flicker caused by the alternating colors of the rotating filter, Short devised a complex projection mechanism where each frame was projected three times by a retractive projector movement, resulting in a quasi-increased frame rate. Little is known about Short and how he and Lady Juliet met, but Lady Juliet credits his “mechanical knowledge and genius” that helped “solve the flicker problem.” (Williams, 1932)

The pair filed patent applications in the UK (October 1930) and the US (August 1931), and in December 1931, Bell & Howell bought the rights to manufacture and sell the filter/projection mechanism with their Filmo 70 camera and Filmo 57 projector. Bell & Howell featured an article about the Morgana color process written by Lady Juliet in for Filmo Topics, June/July 1932, its monthly promotional publication for “personal motion picture makers” and users of its products. The camera was priced slightly cheaper than the comparable model without the Morgana attachment ($245) because it included only one lens instead of three. A full-page advertisement in the same issue of Filmo Topics indicated that the cost of a camera would be $190 and a projector, $210. The equivalent of several thousand dollars in the twenty-first century. The ad also noted that the camera’s “Morgana filter [is] instantly removable for taking B/W or Kodacolor pictures” and similarly, the projector’s “Color wheel is instantly removable for showing B/W films.” There are no known reports on whether the customized mechanism had an effect on how other types of film appeared when projected.

While the customized projection mechanism reportedly eliminated flicker in the projected image, even Bell & Howell’s own advertisements admitted the process still had shortcomings: “The disadvantages of the Morgana Process are less than those of any other two-color additive process. Color rendition, while not so faithful as by a three-color process, is nevertheless very pleasing and artistic. Slight fringing is prevalent with close-ups in fast motion but is not considered objectionable.” (Williams, 1932)

News of the new color process began to circulate in July 1932 with the announcement appearing in amateur cine publications such as Movie Makers and in industry/trade press, such as American Cinematographer, which carried a Bell & Howell advertisement featuring Morgana in its August issue.

Despite this promotion in the press, there is no evidence that the Morgana attachments for cameras and projectors were ever sold commercially, but there are reports that demonstration reels were made. In its November 1932 issue, International Photographer mentions a Morgana demonstration given at the West Coast Society of Motion Picture Engineers (SMPE) meeting the previous month; and in its March 1933 issue, it describes a 350-ft film made by a Bell & Howell employee (most likely Joseph Dubray) of the Pasadena Tournament of Roses earlier that year. The film was shown to an audience of 300 at the Tournament Association’s annual awards banquet and later, a private screening was given to the parade’s grand marshal, Mary Pickford, and her husband, Douglas Fairbanks.

In May 1933, American Cinematographer noted that the Comte (Frédéric) de Janzé of Paris would be experimenting with Morgana color on his hunting expedition to Africa. However, a subsequent article written by de Janzé in Movie Makers, September 1933, makes no mention of the color experiment.

By the early 1930s, other color processes such as Kodacolor and Vitacolor had established a foothold in the amateur market, and with the prospect of more practical and affordable color processes such as Dufaycolor and Kodachrome on the horizon, production of the Morgana color process was abandoned. As a major manufacturer of film and photographic equipment, Bell & Howell would almost certainly have been aware of the imminent arrival of Dufaycolor 16mm, available to the UK market in 1934, offering an accessory-free color option to amateurs, and the development of Kodachrome would have been on their radar too. Along with the economic slump in the early 1930s, it is not surprising that Bell & Howell did not continue manufacturing the Morgana equipment. Simon Brown notes that, “The registrar was informed to dissolve [Morgana Syndicate Ltd] in February 1937 and it was noted at this point that the Morgana patents had been allowed to lapse and that the agreement [with] Bell and Howell was therefore valueless.” (Brown, 2012)

A note about the name “Morgana”: The origins of the name are uncertain but it is possible it could be a reference the county of Glamorgan in south Wales, where Lady Juliet lived, and/or a reference to the character of Arthurian legend, Morgan le Fay (aka Morgana), whose origins lie in Welsh/Celtic mythology.

Selected Filmography

Technology

The Morgana color process took the basic principles of additive processes such as Kinemacolor – a rotating green and red filter attached to the camera using panchromatic B/W film – and applied them to small-gauge equipment and reversal film. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, additive processes were still considered a viable solution for amateur filmmaking and reversal film was well suited to amateurs who mostly did not need to create multiple copies of their work. By her own account, Lady Juliet believed that the two-color rotating filter process was the future of color cinematography if a solution could be found to eliminate the flicker when projected, and the fringing caused, particularly by rapid movement of a subject.

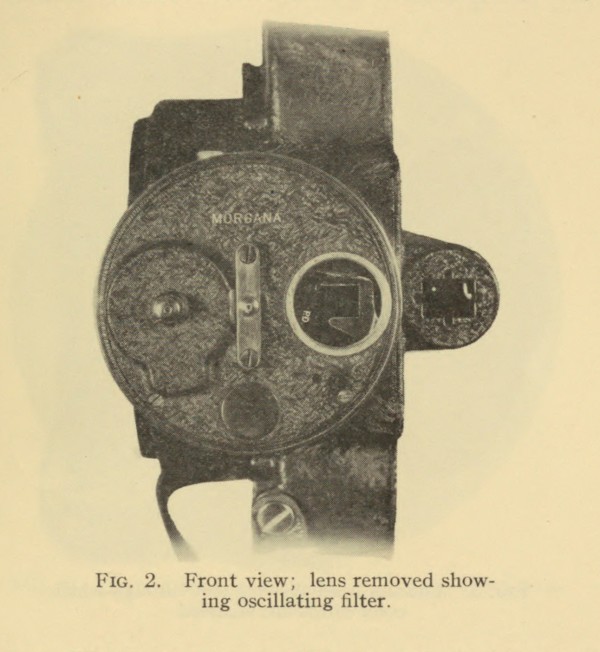

The filter attachment for the camera was available for daylight and tungsten lighting. The intricate projection mechanism designed by George Short was described in detail by Bell & Howell employee Joseph Dubray. Dubray, whose interest in motion pictures reportedly began as a hobbyist building his own equipment in 1898, was a cameraman for Pathé in his native France, before being sent to the US in 1910 to “take charge of the technical work” (Theisen, 1933). He continued to work in the industry until 1929, when “his inclination toward research and engineering […] led him to a connection with Bell & Howell” (Theisen, 1933), where he eventually became manager of standard sales and service. In spring 1933, Dubray presented a detailed technical explanation of Morgana to the Society of Motion Picture Engineers meeting in New York City. (Dubray, 1933)

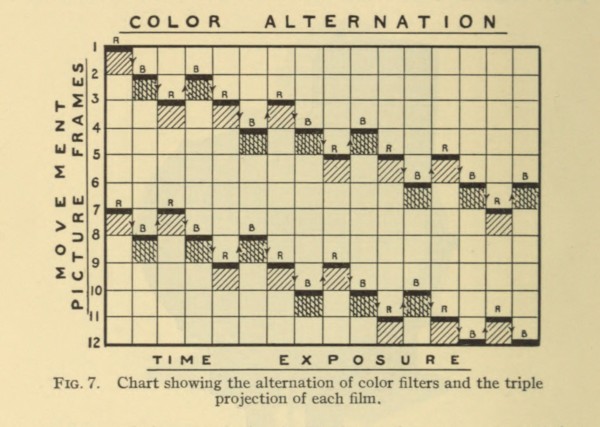

Elimination of the flicker was achieved by a quasi-increased frame rate of 72 frames per second because each frame was effectively being projected three times. “During projection two successive frames move forward and one backward, or in reverse, in the following order: 1-2; 1-2-3; 2-3-4; 3-4-5; etc. The result is that, although the film is running at a linear speed of 24 frames (1⅔ ft) per second, 72 frames are alternating at the aperture during the same length of time, each picture frame being projected three times on the screen. This accrued projection speed eliminates color flicker and greatly reduces color fringing.” (Dubray 1933)

When editing and splicing film, care had to be taken to ensure that alternation of the red and green frames was retained so that synchronization of the rotating filter and the projected frame was not lost. A small white rectangle just above alternate perforations on the left edge denoted which frames were exposed through the green filter. To the naked eye, the tonal differences between the frames are barely noticeable, but if a Morgana film was projected without the rotating red and green filter, a significant flicker would be visible.

Regardless of these improvements to the stability of the image, the rendition of a full spectrum of colors was destined to fall short because Morgana was a two-color, rather than a three-color process. Other additive processes such as lenticular Kodacolor and the imminent Dufaycolor used three colors, so by 1933, the introduction of a two-color process would have been considered a step backwards. Dubray downplayed this by stating that “the only colors that are really lost are the deep purples, magentas, and rich yellows”. (Dubray, 1933) Even though Bell & Howell was aware of Morgana’s disadvantages and potentially the industry-wide shift away from additive color processes, they continued to emphasize Morgana’s distinguishing features:

1. It used regular panchromatic reversal film.

2. Reversal prints could be made directly from panchromatic reversal originals.

3. Any Film lens could be used. The filters in the camera were behind the lens seat.

4. Pictures could be taken under adverse light conditions. Although the aperture had to be opened one stop to compensate for light absorbed by the two-color filters

5. Screen pictures 10 feet wide could be shown with a Filmo projector(Anon., 1932a)

None of this, though, was enough for Morgana to be manufactured and sold on the commercial market. No apparatus or films are known to survive. Despite Morgana’s commercial failure, the innovation of Short’s projection mechanism can still be appreciated for its technical ingenuity.

The two-color filter wheel was mounted inside a custom Bell & Howell Filmo 70 16mm camera between the lens and the film.

Dubray, J. (1933). “The Morgana Color Process”, Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (November 1933): p. 405.

Chart showing the alternation of color filters and the triple projection of each film frame.

Dubray, J. (1933). “The Morgana Color Process”, Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (November 1933): p. 410.

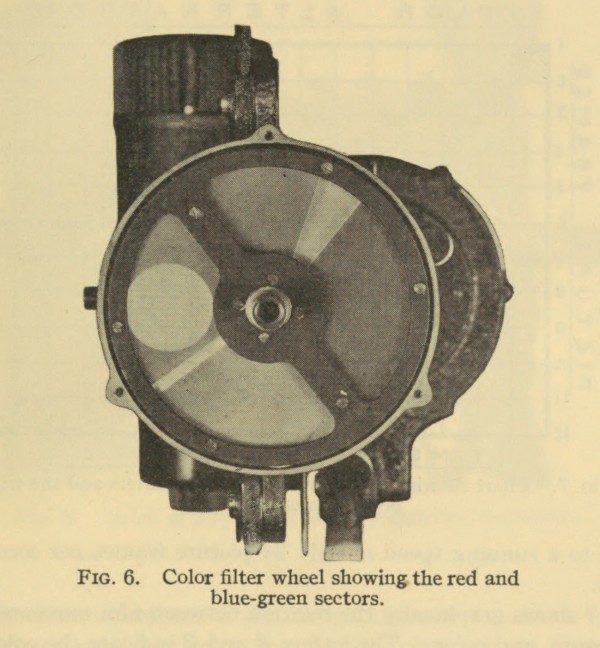

With the lens mount removed, the color filter wheel is visible in front of the projector’s film gate.

Dubray, J. (1933). “The Morgana Color Process”, Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (November 1933): p. 409.

References

Anon. (1932a). “Morgana Color Process for Filmo Cameras and Projectors”. Movie Makers (July): p. 285. https://archive.org/details/moviemakers07amat/page/284/mode/2up?view=theater

Anon. (1932b). “Filmo Camera and Projector for Morgana Color Process”. American Cinematographer (August): p. 1. https://archive.org/details/americancinemato12amer/page/n377/mode/2up?view=theater

Anon. (1933). “Comte de Janze Doing Color Picture”. American Cinematographer (May): p. 28. https://archive.org/details/americancinematographer13-1933-05/page/n25/mode/2up?view=theater

Anon (1933). “In Morgana Color”. The International Photographer (March): p. 39. https://archive.org/details/internationalpho05holl/page/n149/mode/2up?view=theater

Brown, Simon (2012). Quoted in Street, Sarah, Color Films in Britain. The Negotiation of Innovation 1900–55. London: BFI/Palgrave Macmillan: p. 277.

Coe, Brian (1981). The History of Movie Photography. Westfield, New York: Eastview Editions.

Dubray, Joseph (1933). “The Morgana Color Process”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (November): pp. 403–412. https://archive.org/details/journalofsociety21socirich/page/402/mode/2up?view=theater

Glyn, Elinor. Papers of Elinor Glyn, UoR MS 4059, University of Reading Special Collections Services, University of Reading, UK.

Janzé, Count de (1933). “Where Lions Prowl”. Movie Makers (September): pp. 368, 377. https://mediahist.org/reader.php?id=moviemakers08amat

Theisen, Earl (1933). “The Story of Bell & Howell”. International Photographer (October): pp. 6–7, 24–25. https://archive.org/details/internationalpho05holl/page/n439/mode/2up?view=theater

Williams, Juliet (1932). “A Seven Years Dream – has culminated in the introduction of the Morgana Color Process for Filmo Cameras and Projectors”. Filmo Topics (June/July): pp. 4, 9. https://mediahist.org/reader.php?id=filmotopics8910bell

Williams; Juliet Evangeline Rhys (1898–1964). Collection. London School of Economics Library, London, UK. https://archives.lse.ac.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=RHYS+WILLIAMS+J

Patents

Short, S.G. et al. Apparatus for use in color cinematography. US Patent 1,931,512, filed August 8, 1931, and issued October 24, 1933.

Short, S.G. Color or other cinematography. US Patent 1,954,943, filed August 8, 1931, and issued April 17, 1934

Compare

Related entries

Author

Louisa Trott is a graduate of the University of East Anglia’s film archiving master’s program and has worked with small-gauge and amateur film collections at regional and national film archives in the UK and US. In 2005, she co-founded the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound in Knoxville. Since 2021, she has been Arts & Humanities Librarian and Associate Professor at the University of Tennessee.

I would like to acknowledge the often-invisible work of collectors, archivists, and librarians who have collected, arranged, described, preserved, and provide access to print publications and personal papers. Online access to many materials has made materials infinitely more accessible. I would also like to acknowledge the efforts of those who have scanned, created metadata, and continue to provide access to digital surrogates of these publications. Thanks to Tracey Tiller, and Frank and Rosemary Trott for their research efforts at the London School of Economics and the Glamorgan Archives on my behalf, and to relatives of Lady Juliet for insights into the Rhys Williams family.

Trott, Louisa (2024). “Morgana Color”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.