An additive three-color screen process, based on a photographic process originated by Louis Dufay. The first commercially produced reversal natural color process for amateur cinematographers that did not require special attachments on the camera or projector to produce color.

Film Explorer

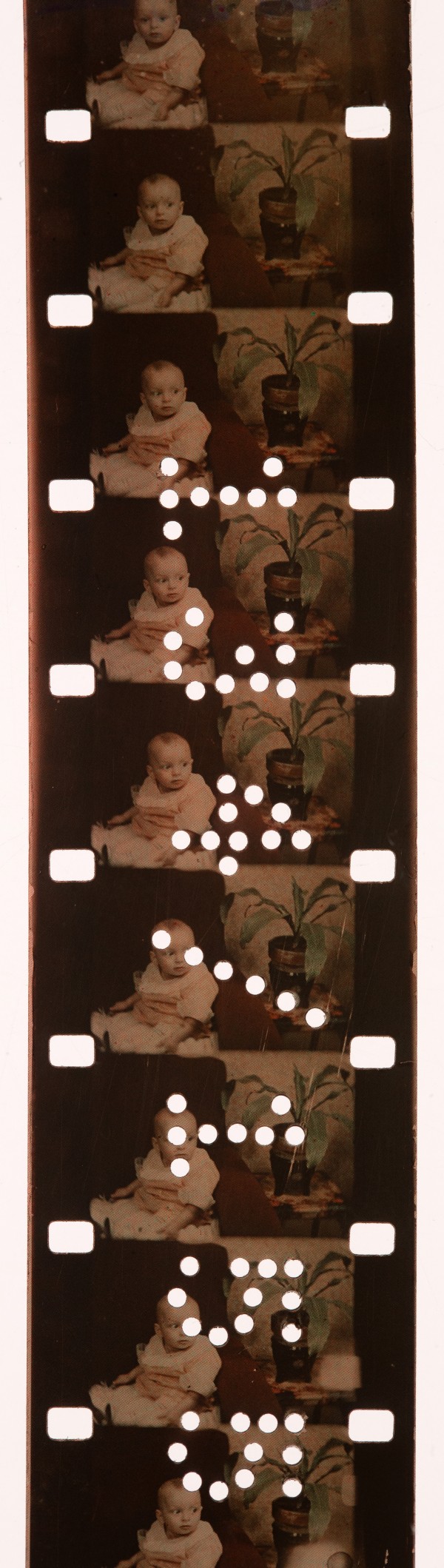

An unidentified home movie shot on 16mm reversal Dufaycolor, c. 1930s. This example includes a unique identifier number punched into the film by the processing lab.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

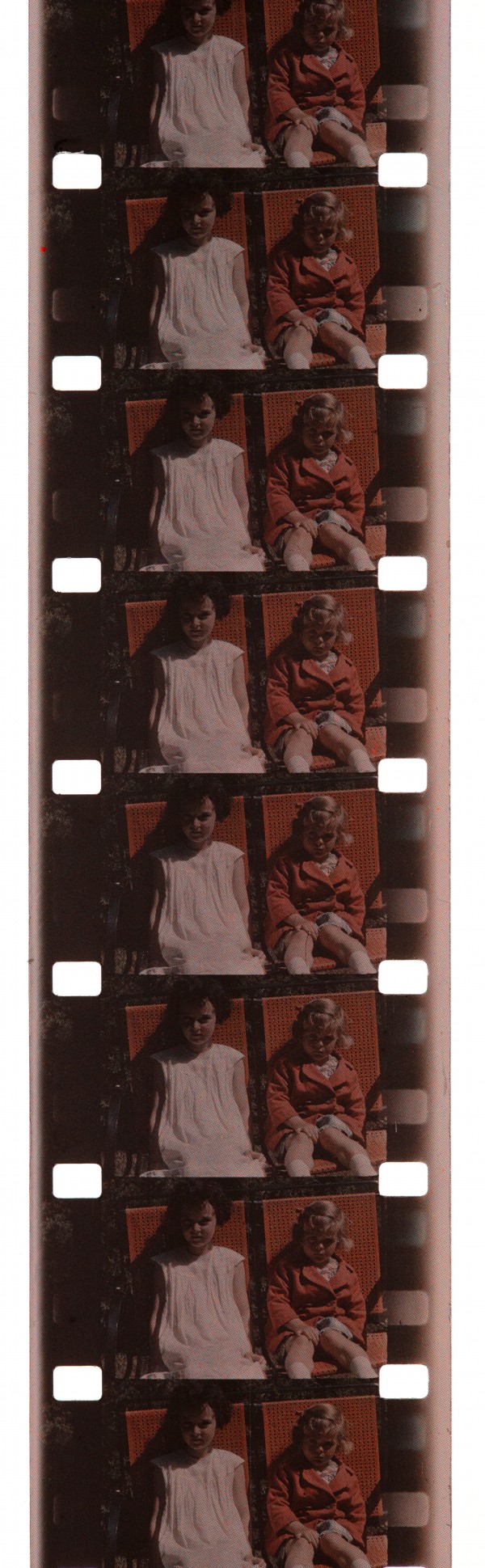

An unidentified home movie shot on 16mm reversal Dufaycolor, c. 1930s. The colored réseau filter pattern on the film’s base absorbed some of the incoming light, resulting in dimmer exposures.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States

Frames from an early 35mm Dufaycolor demonstration film, c. 1931. Even though the emulsion layer is peeling, the colored réseau, applied directly to the film base, is still visible.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States

Identification

Full spectrum of muted colors. Often dark due to underexposure. Occasionally, red blotches are visible on the image, due to red dye being applied last in the réseau manufacturing process.

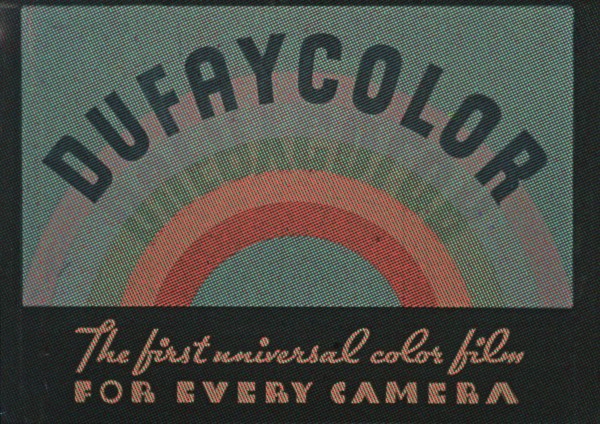

“Photographed on Dufaycolor Substandard film” (16mm, UK); “The End, Dufaycolor” (9.5mm, UK); “Dufaycolor” rainbow logo (16mm, US?)

8mm examples exist but there is no evidence that it was commercially available.

Panchromatic B/W reversal emulsion exposed through a three-color mosaic pattern (réseau) in the base. The emulsion was made and applied to the base by Ilford in the UK and Dupont in the US.

None.

History

Dufaycolor was an additive three-color screen process based on a technique originally developed for photographic glass plates by Louis Dufay in France. Dufay’s original screens employed a uniformly structured mosaic pattern of four colors, which he patented in 1908 as Diopticolore – he began manufacturing glass plates under the name Dioptichrome the following year. In 1917, Dufay applied the same process to positive photographic film using his new company name, Société Versicolor.

As manufacturers of paper and film products, including cellulose acetate wrapping material, the owners of Spicer Ltd in Cambridgeshire, England, were aware of the burgeoning market in photographic cellulose acetate “safety” film. Seeking to expand their product range, and with a keen interest in investing in the quest for a commercially viable natural color film process, Spicer Ltd purchased the rights to the line-screen process from Louis Dufay in 1926. The company provided initial financial backing with technical guidance provided by employees A. Dykes Spicer and S. R. Wycherley (Carson, 1934: p.19). T. Thorne Baker, an engineer with expertise in photochemical processes, who had previously worked with Louis Dufay in France, and engineer Charles Bonamico were hired to carry out extensive research and development in the manufacturing of the color screen process, which they called the réseau – French for network or grid. That same year, Dufay, Baker and Bonamico shot several thousand feet of negative in the south of France on 8-lines per mm réseau and showed the prints at the Pavilion Theatre in London. (Cornwell Clyne, 1951: p.20)

In spring 1931, an improved 20-lines per mm Dufaycolor 35mm motion picture film was demonstrated at the Royal Society in London, and again, later that year, at the British Kinematograph Society. In 1932, another demonstration was made at the Film Society in London and, that same year, Ilford Ltd and Colortone Holdings Ltd joined Spicer Ltd to form Spicer-Dufay (British) Ltd. Production of the film stock was divided between Spicer’s Sawston, Cambridgeshire, factory where the réseau was made, and Ilford’s Brentwood, Essex, factory where the light-sensitive emulsion was applied. The following year, the company changed its name to Dufaycolor Ltd, and also registered Dufaycolor, Inc. in the United States.

On April 20, 1934, the first public demonstration of 35mm and 16mm Dufaycolor was held at the Savoy Hotel in London. Initially, Spicer’s primary interest was in producing a viable color solution for the motion picture industry, particularly as a competitor to Technicolor – but realizing a viable negative-positive, scalable process proved technically challenging. However, as a 16mm direct-positive reversal process, Dufaycolor was enthusiastically embraced by amateur filmmakers upon its UK launch in the late summer of 1934. Kodacolor and Vitacolor had enjoyed some success among amateur filmmakers since the late 1920s but had largely fallen out of use by 1934. Both processes required additional, sometimes costly, equipment to create and project the color, but Dufaycolor’s réseau meant that the color was integral to its film stock, so no proprietary accessories were required. A 50ft-reel cost 21 shillings (one guinea – a pound and one shilling), which included processing.

W. H. Carson, vice-president of Dufaycolor, Inc., presented the process to the Society of Motion Picture Engineers in Atlantic City, NJ, in spring 1934. But, due to delays with securing US licensing, it wasn’t until spring 1935 that 16mm Dufaycolor hit the US market – coinciding with the launch of Kodachrome. While Kodachrome’s subtractive process offered the amateur greater ease of use, problems with the dye couplers in its first three years – causing a distinctive red cast – initially allowed Dufaycolor to claim a portion of the amateur market. Its practicality, and relative affordability, made Dufaycolor popular with amateur filmmakers and in 1937 9.5mm Dufaycolor reels and Pathéscope cassettes were introduced in Europe.

Dufaycolor 8mm is mentioned in several issues of International Photographer throughout the summer of 1936, and the authors of Silver by the Ton note that there may have been plans to introduce 8mm, but there is no evidence that it was ever produced for the retail market. Some sample frames of unslit double 8mm are held in the Film Frame Collection at the Seaver Center, Los Angeles, CA, and the contact information on the storage envelope – Film Specialists in El Monte, California – matches the company mentioned in International Photographer, but the exact nature of the connection is unknown. In 2015, a poorly slit double 8mm home movie was discovered in a private collection and subsequently donated to the University of Southern California’s HMH Moving Image Archive, but otherwise, there is no evidence that 8mm Dufaycolor was manufactured and sold commercially.

In 1937, T. Thorne Baker moved to New York to work as technical consultant at Dufaycolor, Inc. (Kinematograph Yearbook, 1937: p. 307) Adrian Klein, later Cornwell-Clyne, was hired by, what was now known as, Dufay-Chromex (the company had merged the previous year with Chromex, a holding company for the takeover of British Cinecolor [Street, 2012: p.270]) to oversee research and development and to act as spokesperson for the Dufaycolor process – promoting it for commercial use. During this time, a new laboratory for product development and processing was opened at Thames Ditton, Surrey, England.

During World War II, Dufay-Chromex turned its Sawston-based factory over to the war effort, pausing research and production of photographic film. Postwar, it became clear that the future of color motion picture film was in subtractive processes. Production of film for stills photography – both color and B/W – continued for a few years. The 1949 edition of the Dufaycolor Data Book contains an extensive list of Dufaycolor distributors around the world, but any mention of Dufaycolor for the amateur filmmaker had all but disappeared. Operations at the factory finally ceased in 1955.

Dufaycolor “ident” from the amateur film Doggies – new color (1930s), photographed on 16mm reversal film.

Theodore Dru Alison Cockerell Papers, University of Colorado Boulder Libraries, Special Collections & Archives, Boulder, CO, United States.

A box and reels for 9.5mm reversal Dufaycolor. The red and yellow branding was used in the United Kingdom; blue and white was used in the United States (16mm).

Courtesy of David Pfluger, Bern, Switzerland.

Selected Filmography

Part of a compilation of 16mm home movies – a mix of B/W, Dufaycolor, and Kodachrome – from the collection of Theodore Dru Alison Cockerell, a professor of zoology at the University of Colorado. https://cudl.colorado.edu/luna/servlet/detail/CUB~11~11~413~226825

Part of a compilation of 16mm home movies – a mix of B/W, Dufaycolor, and Kodachrome – from the collection of Theodore Dru Alison Cockerell, a professor of zoology at the University of Colorado. https://cudl.colorado.edu/luna/servlet/detail/CUB~11~11~413~226825

9.5mm Dufaycolor footage shot in and around Ilford’s Selo Research Lab in Brentwood, Essex, UK. https://eafa.org.uk/work/?id=1051776

9.5mm Dufaycolor footage shot in and around Ilford’s Selo Research Lab in Brentwood, Essex, UK. https://eafa.org.uk/work/?id=1051776

A 9.5mm home movie from Czech couple Josef Zelinka and Helena Zelinková, collection at the Austrian Filmmuseum. https://www.filmmuseum.at/en/collections/film_collection/film_collection_insights/donation_zelinka

A 9.5mm home movie from Czech couple Josef Zelinka and Helena Zelinková, collection at the Austrian Filmmuseum. https://www.filmmuseum.at/en/collections/film_collection/film_collection_insights/donation_zelinka

A 9.5mm home movie filmed in Orléans, France, which includes some Dufaycolor scenes. https://memoire.ciclic.fr/4887-une-communion-a-orleans

A 9.5mm home movie filmed in Orléans, France, which includes some Dufaycolor scenes. https://memoire.ciclic.fr/4887-une-communion-a-orleans

A portrait of a brick and tile manufacturer, made by an unknown amateur filmmaker, includes some brief Dufaycolor scenes. https://screenarchive.brighton.ac.uk/detail/455/

A portrait of a brick and tile manufacturer, made by an unknown amateur filmmaker, includes some brief Dufaycolor scenes. https://screenarchive.brighton.ac.uk/detail/455/

Technology

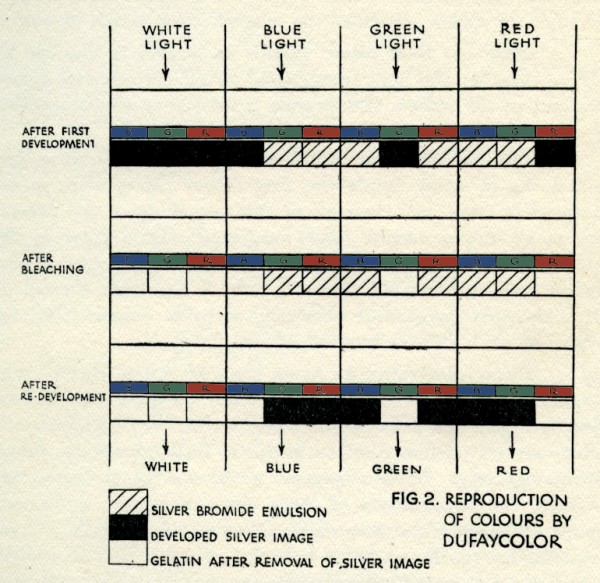

Dufaycolor was the first additive color motion picture film that did not require additional filters or attachments on the camera or projector. The filters were integral to the film itself, applied to the film base in a crosshatch pattern of red, green and blue lines. The film was loaded into the camera with the three-color screen (the réseau) in the film’s base facing the lens so that light entering the lens passed through the colored screen before exposing the film’s black and white panchromatic emulsion. (This was the opposite of how standard B/W film was exposed.) Light from a red object passed through the red parts of the réseau but was filtered in varying degrees by the green and blue parts. When the film was developed, the area of the film where the red object had exposed the emulsion would remain clear so when projected (with the réseau facing the projector lamp), that area would appear red on the screen.

The technique for applying the réseau’s miniscule colored lines (20 lines per mm) to the film base was developed and refined over several years by color experts and engineers hired by Spicer and Ilford for their expertise in photography and engineering. T. Thorne Baker and Charles Bonamico’s extensive research in refining the machinery and processes used to manufacture the réseau, extended outside of the world of photography, consulting with color experts such as dyers and colorists.

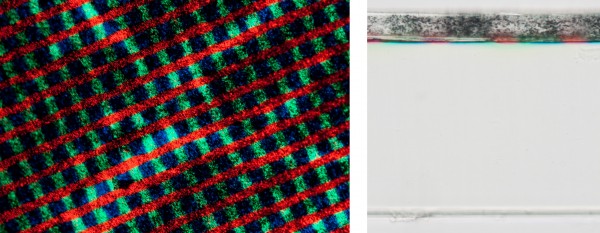

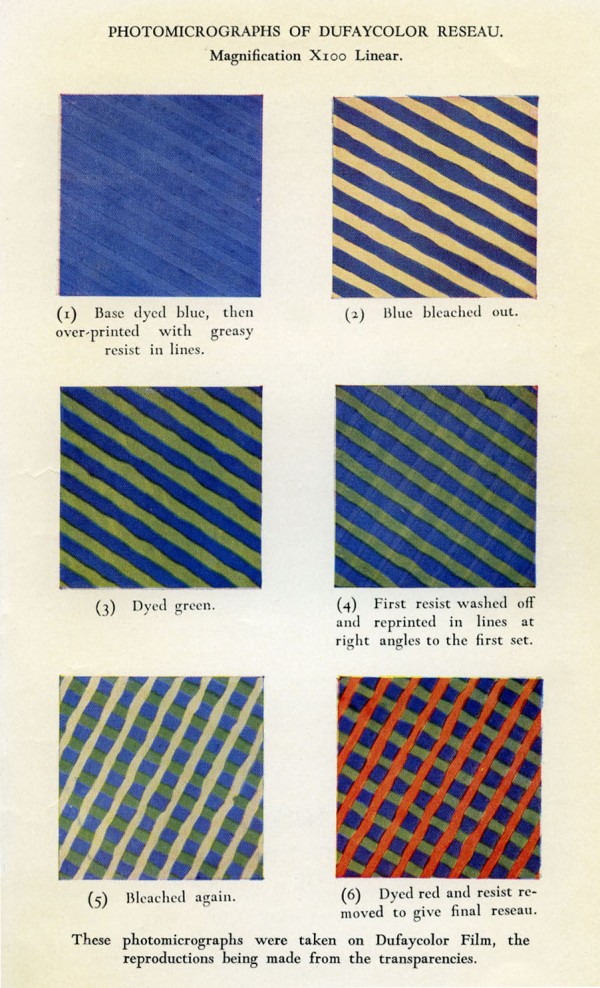

Manufacture of the réseau was an intricate, multi-stage process and required rigorous quality control at each step. Simply explained, using a cylinder engraved with a helical groove, the blue ink was was added first. After drying, areas that were treated with a resist (to prevent the dye sticking) were cleaned and bleached, and the film went through the same processes for the green and lastly the red dyes. Adrian Cornwell-Clyne provides a detailed description of the manufacturing process in his book Colour Cinematography (1951). Once the réseau had been applied, the final layers of gelatin and a varnish were applied before the film stock was sent to Ilford Ltd to be coated with the panchromatic emulsion.

Although improvements were made to the emulsion’s speed (it was about half that of standard panchromatic film), the amount of light absorbed by the réseau when filming and projecting remained problematic, resulting in an overall darker image.

When 16mm and 9.5mm home movies were projected a short distance from the screen, the réseau was usually visible, but not intrusively so. The amount of light absorbed by the réseau, particularly from a typical home movie projector, meant that the projected image could appear dull. For most amateurs though, the novelty of color outweighed – at least for a while – the lesser concerns of image quality.

Microscopic (x20), left; and cross section (x50), right, images of Dufaycolor film. The B/W emulsion layer sits on top of the colored réseau – red, green, and blue applied directly on the film base.

George Eastman Museum / Image Permanence Institute, Rochester, NY, United States.

A diagram illustrating how light was filtered through the red, green and blue réseau pattern to create an image on the B/W panchromatic emulsion which, when developed and projected back through the réseau, created a color image on the screen.

The Dufaycolor Book (Dufay-Chromex Ltd., 1937). Modified with color by Crystal Kui.

Photomicrographs showing the stages in creating the réseau.

The Dufaycolor Book (Dufay-Chromex Ltd., 1937)

References

Anon. (1936). “Notes on Projecting Dufay-Color Film”. International Photographer (May): p. 22.

Baker, T. Thorne (1932). “The Spicer-Dufay color film process”. Photographic Journal, 7:109: pp. 109–17.

Brown, Simon (2002). “Dufaycolor – the Spectacle of Reality of British National Cinema”. Centre for British Film and Television Studies, 2002 https://web.archive.org/web/20230609042455/http://www.bftv.ac.uk/projects/dufaycolor.htm (accessed August 27, 2024).

Carson, W.H. (1934). “The English Dufaycolor Film Process”. Journal of the SMPE, 23:1 (July: pp. 14–26.

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian (1951). Colour Cinematography (3rd rev. edn). London: Chapman and Hall.

Coote Jack H. (1993). The Illustrated History of Colour Photography. Surbiton: Fountain.

Dufay-Chromex Ltd. (1937). Dufaycolor Book, The. Elstree, Herts: Dufay-Chromex Ltd.

Dufay-Chromex Ltd. (1949). Dufaycolor Data Book, The. Elstree, Herts: Dufay-Chromex Ltd.

Filmcolors.org (n.d.). Timeline of Historical Film Colors. https://filmcolors.org/ (accessed August 17, 2024).

Harrison, G.B. (1935). “Dufaycolor”. Proceedings of the British Kinematograph Society, 33 (September): pp. 3–7.

Hercock, Robert J. & George A. Jones (1979). Silver by the Ton: The History of Ilford Limited, 1879–1989. London: McGraw-Hill.

Howe, Bryan (2002). The Dufaycolor Story: One of Britain’s Past Industries. Sawston: Link Publishing.

Kinematograph Publications Ltd. (1937). Kinematograph Year Book. London: Kinematograph Publications Ltd.

Ormes Ian (1997). From Rags to Roms : A History of Spicers 1796–1996. Cambridge: Granta Editions.

Street, Sarah (2012). Colour Films in Britain: The Negotiation of Innovation 1900–55. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Welford, S.F.W. (1988). “Dufaycolor”. History of Photography (January/March): pp. 31–5.

Patents

Dufay, Louis; Compagnie d’Exploitation des Procédés de Photographie en Couleurs Louis Dufay. Improvement in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB217557, filed April 16, 1924, and issued February 26, 1925.

Spicers Ltd; John Naish Goldsmith; T. Thorne Baker; Charles Bonamico. Improvements in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB333865, filed June 1, 1929, and issued August 21, 1930.

Goldsmith, John Naish; Spicer Ltd. Improvement in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB334243, filed May 30, 1929, and issued September 1, 1930.

Thorne Baker, Thomas; Dufaycolor Limited. Improvement in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB420824, filed June 6, 1933, and issued December 6, 1934.

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Louisa Trott is a graduate of the University of East Anglia’s film archiving master’s program and has worked with small-gauge and amateur film collections at regional and national film archives in the UK and US. In 2005, she co-founded the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound in Knoxville. Since 2021, she has been Arts & Humanities Librarian and Associate Professor at the University of Tennessee.

Thank you to all who have shared their knowledge and collections of Dufaycolor with me over the years, but the biggest thanks go to David Cleveland and Jane Alvey who encouraged me to dive deeper into Dufaycolor history through its East Anglian connections.

Trott, Louisa (2024). “Dufaycolor (reversal)”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.