A two-color process, invented by Emil Wolff-Heide.

Film Explorer

This Wolff-Heide film test was likely made by Hans Fraunhofer, in September 1932. The use of pinacyanol, pinatype blue D, and other similar sensitizers, gave the edges of the film a distinctively teal, or dark cyan, color.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

This Wolff-Heide film test was likely made by Hans Fraunhofer, in September 1932. Both the negative (pictured here), and the print, were processed similarly, with the application of color-sensitive chemicals before, and after, exposure or printing.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

B/W, orthochromatic; but, partially resensitized to panchromatic on the surface.

Standard Agfa and Eastman Kodak markings.

Earlier versions of the process ran at 28–32 fps and 16–20 fps.

1

An emulsion layer of the B/W negative and the print was chemically treated before and after exposure, which applied colors to the film, after processing.

Unknown

Surviving 35mm example are standard silent aperture: 24mm x 18mm (0.980 in x 0.735 in).

B/W, orthochromatic; but, partially resensitized to panchromatic on the surface.

Standard Agfa and Eastman Kodak markings.

History

Wolff-Heide was a series of color processes, devised by German photo-chemist Emil Wolff-Heide.

During the 1920s, with his business partner Hans Fraunhofer, engineer Johann Szemzo, and advisor (Geheimrat) Emi Klamt, Emil Wolff-Heide developed, and registered several patents for, a set of additive and subtractive color processes. The most famous version of his invention was a subtractive method for applying chemicals, to produce red and blue color strata (layers) in one emulsion.

In September 1926, Wolff-Heide presented the process in Berlin. Witnesses praised the process – for instance, Time magazine reported that “colors of the spectrum were faithfully reproduced, and delicately shaded even at the violet [short-wave] end” (Time Inc., 1926). Despite the positive reviews, the invention was not adopted for film production at this time.

In 1928, a consortium of bankers from Dortmund, in Germany, and Glarus and Zurich in Switzerland, became interested in buying the process and patents, to exploit under the name Photochrome A-C – but, ultimately, this approach did not come to fruition.

Around the same time, Emil Wolff-Heide’s business partner, Hans Fraunhofer, attempted to enter the rapidly growing American color cinematography market. In New York, he founded a number of companies, including Photochrome Inc. and Wolff-Heide Photochemical Co., and also a new corporation, United Film Industries Inc.

In the US, the target audience for the process seemed planned to be both professional and amateur filmmakers (reports indicate it was being developed for 35mm, 16mm and 9.5mm cinematography) (Fraunhofer, 1929). The process was promoted as cheap (from one to fourteen cents per foot) and easy to use. A standard camera could be used – the film was given a special chemical treatment, before and after exposure, to sensitize it for color production.

Specialist magazines hailed the Wolff-Heide process as a “practical solution … for true-to-nature colors”. It was also declared that color fringing in the projected film was eliminated, and colors did not fade (National Sportsman, 1928).

In June 1929, Emil Wolff-Heide joined Fraunhofer in New York for a demonstration of the process. On November 12, 1929, the “revolutionary disclosure in all branches of color photography” (Herald-World [Special Correspondent], 1929) was also presented in Ardmore, near Philadelphia, where the American Wolff-Heide laboratory was founded.

At the same time, some issues with the process began to be noticed by observers. For example, in 16mm demonstrations, unsatisfactory toning resulted in noticeably visible grain (National Sportsman, 1928) with an "unnatural preponderance of the gaudy orange-red” (Herald-World [Special Correspondent], 1929).

In 1929, a group of businessmen, distributors, and producers, from Philadelphia, announced they would invest $125,000 in the Wolff-Heide process. Later, plans were announced to construct a plant in Hollywood capable of producing 200 million ft (60,960,000m) of chemically sensitized B/W film annually (Fraunhofer, 1929).

Despite these high hopes, the fate of the process became obstructed by legal setbacks. First, in 1931, Frauenhofer sued the Philadelphia businessmen, accusing them of failing to provide the promised investments (Film Daily, 1931b; Motion Picture Herald, 1931; Variety, 1931). Second, Emi Klamt, a former German companion of Wolff-Heide, accused Frauenhofer and Henry Zollinger (Chairman of the Board of Directors of Photochrome Inc., New York) of stealing the rights to the process (New York Times, 1936; Variety, 1936).

After 1934, Frauenhofer applied for several patents for color monopack film on behalf of his newly formed companies, Omnichrome Corp. and Trichrome, Inc. After 1937, Wolff-Heide’s ideas were picked up by Joseph S. Friedman and Arthur Bruck, on behalf of yet another new firm, Color Processes, Inc. These descendants of the Wolff-Heide process also never achieved wide usage.

Newspaper portrait of Emil Wolff-Heide.

Bergische Zeitung (1926). “Das Problem der Farbenkinematographie geloft”. Bergische Zeitung (Sep. 21): p. 9.

To exploit the Wolff-Heide process, and its derivatives, Hans von Fraunhofer registered numerous companies in the United States – and later, in the United Kingdom.

“Year Book of Motion Pictures”. The Film Daily, 1931, p. 1091.

When Hans von Fraunhofer promoted the color process, he exploited the reputation of Wolff-Heide as a sophisticated inventor with a history of producing affordable new products for consumers.

Düsseldorfer Stadt-Anzeiger (Sep. 19, 1926): p. 8.

Technology

The Wolff-Heide color process went through several iterations and improvements. In the early 1920s, Emil Wolff-Heide experimented with superimposing two colors during projection, using a rotating disc to create an additive color image. Later, he also considered double-coated prints with one color record printed on each side – and then sensitizing alternate frames of a single emulsion on one side of the film.

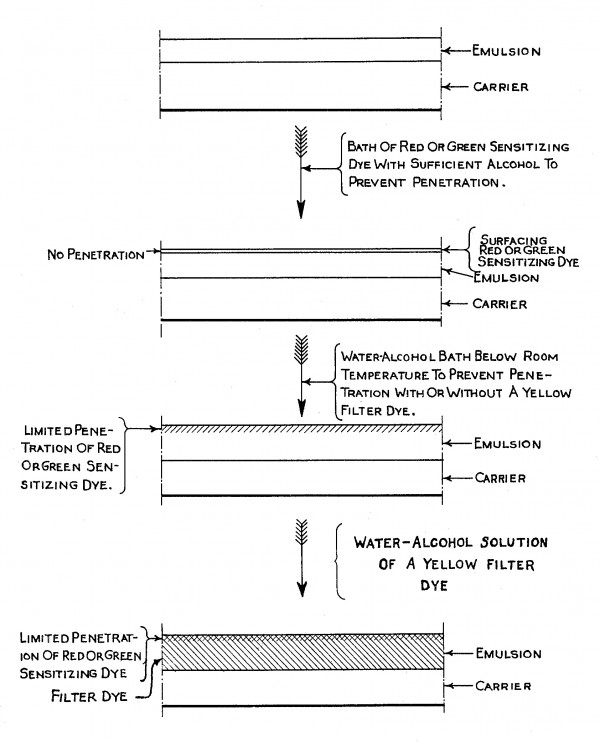

However, in the late 1920s, Wolff-Heide made a pivotal breakthrough in his research. This involved a chemical treatment that allowed red and blue sensitizers to penetrate, and disperse, to different depths within a single emulsion layer of a standard B/W film. The surface of the emulsion became sensitive to one color, while the lower levels of the emulsion were sensitized to another part of the spectrum – thus, a two-color image could be recorded.

Generally, this treatment was similar to the collodion photographic process. According to Joseph S. Friedman, who worked with Wolff-Heide in 1931, the origins of the idea were rooted in the “hydrotypes” invented in France, in 1881, by the brothers Charles and Antoine-Hippolyte Cros – and further elaborated in Germany, in 1905, by Ernst König of the Farbwerke Hoechst AG. (Emil Wolff-Heide used dyes from the same manufacturer.) Independently, similar ideas were developed by Leonard Troland at Technicolor; and Leopold Mannes and Leopold Godowsky, for Eastman Kodak in the United States – the fundamental basis of future multilayer, monopack color processes, such as Kodachrome and Eastman Color.

In Wolff-Heide’s method, an unexposed B/W film was treated, at a relatively cold temperature (around 40–45°F/4–7°C) for a couple of minutes, in baths of alcoholic solution and sensitizing chemical agents. Although the recipe of the mixtures varied slightly, in general, uranium nitrate, erythrosine, or rose Bengal, were used to form an upper, red stratum; and pinacyanol, pinaflavol, or Prussian blue, formed a blue-green stratum, at lower levels. The gelatin absorbed these mixtures, dispersing them among the silver halide particles, already held in a matrix within the emulsion.

After exposure and processing, the film required another chemical treatment – involving the consecutive use of uranium intensifier, ferric ammonium oxalate and hydrochloric acid – followed by additional washing in a sodium thiosulfate solution.

The print was made in a similar fashion to the negative.

“The colored negative was contact-printed upon another surface-sensitized film. The red rays, modulated by the silver image plus pinatype dye, would yield a latent image in the upper stratum of the positive film. The blue rays, modulated by the red-toned uranium image, gave a latent image in the bottom portion. The processing technique was identical with the one used for making the negative. In the final print, therefore, there was a red-toned image that was supposed to represent a copy of the bottom or blue density image in the negative, while the blue stain modulated by the silver image was a record of the red tones in the colored negative.” (Friedman, 1945: pp. 317–18).

The same sensitizing method, based on Wolff-Heide ideas, was proposed by Joseph S. Friedman for use in still photography, in the late 1930s. The surface of the emulsion was sensitized, using a red, or green, dye to record one color record; while the remainder of the emulsion underneath was treated with a filter dye, to record another color record.

Friedman, Joseph S., Arthur Bruck. Color sensitive photographic plate and method of producing same. US Patent no. US2175836A, filed March 11, 1937, and issued October 10, 1939.

References

Amateur Cinema League (1928). “Color Film”. Movie Makers (January–May). New York, NY: Amateur Cinema League, p. 342.

American Society of Cinematographers (1929). “New Color Process to Appear This Month”. American Cinematographer, 10:2 (May): p. 28.

Anon. (1930). “Sponable Fox R&D Colors”. Film Color Processes (May 30): pp. 16–18.

Beckumer Volks-Zeitung (1926). “Das Problem der Farbenkinematographie geloft”. Beckumer Volks-Zeitung (September 21): p. 5.

Bergische Zeitung (1926). “Das Problem der Farbenkinematographie geloft”. Bergische Zeitung (September 21): p. 9.

Berliner Börsen-Zeitung (1926). Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, 166 (April 10): p. 11.

Berliner Börsen-Zeitung (1928). Berliner Börsen-Zeitung (September 14): s. 10.

Bourquin, Hans (1927). “Farbenkinemotagraphie nach Wolff-Heide”. Photographische Korrespondenz, 6:755 (June 1): p. 186-187.

Crowther, Raymond E. (1923). “Colour Photography”. British Journal of Photography (Monthly Supplement on Colour Photography), 18:201 (July 6): pp. 417–18.

Düsseldorfer Stadt-Anzeiger (1926). Düsseldorfer Stadt-Anzeiger. (September 19): p. 8.

Exhibitor Herald & MPW (1928). “New Natural Film Color Process Demonstrated”. Exhibitor Herald and Moving Picture World (April 7): p. 23.

Film Daily (1927). The Film Daily. May 1, 1927, p. 13

Film Daily (1931a). “United Film Industries, Inc., Introducing New Color Process”. The Film Daily (January 21): pp. 1-2.

Film Daily (1931b). “United Film Ind. Sues Phily Men For Million”. The Film Daily (August 10): pp. 1, 8.

Forrest, J. L. & F. M. Wing. “The New Agfacolor Process”. Journal of the SMPE, 29:3 (September): p. 253.

Fraunhofer, Hans von. (1929). “Wolff-Heide Color Process”. The Motion Picture Projectionist. (April): p. 15.

Fraunhofer, Hans von. (1932). “Another View of Color Photography”. The Motion Picture Projectionist (August), , pp. 6-8, 32-33.

Friedman, Joseph S. (1945). History of Color Photography. Boston: American Photographic Publishing Company, pp. 97–102, 317–18.

Grote, Gustav. “Neues in der Farbenphotographie”. Photographische Korrespondenz (November), s. 285.

Herald-World (Special Correspondent) (1929). “Much Cheaper Natural-Colored Films Claimed for New Method”. Exhibitor Herald-World (November 16): p. 25.

Kinematograph Publications Ltd (1932). “Colour Kinematography”. In The Kinematograph Year Book (1932). London : Kinematograph Publications Ltd, p. 240.

Morgen-Zeitung (1926). “Problem der Farbenkinematographie geloft”. Morgen-Zeitung (September 18): p. 1.

Motion Picture Daily (1931). “United Film Inc. Meet”. Motion Picture Daily (August 11): p. 9.

Motion Picture Daily (1937a). “Restraint Granted in Color Film Suit”. Motion Picture Daily (September 8):. pp. 1, 9.

Motion Picture Daily (1937b). “Dismisses Color Film Suit”. Motion Picture Daily (December 3): p.8.

Motion Picture Herald (1931). “McGuirk, Others Sued for Million”. Motion Picture Herald (August 15): p. 27.

Motion Picture Herald (1932). “New Color Process Ready for Market”. Motion Picture Herald (September 3): p. 28.

Motion Picture Projectionist (1929). “Wolff-Heide Process”. The Motion Picture Projectionist (November): p. 42.

National Sportsman (1928). “Amateur Movies for the Outdoor Man”. National Sportsman (October): pp. 36–7, 49

Neue Mannheimer Zeitung (1928). Neue Mannheimer Zeitung (September 15): s. 12.

New York Times (1936). “Gerard is Named in Color Film Suit; Two German Women Ask Writ Against Him and Others to Bar Use of Optical Device”. The New York Times (August 14): p. 38.

Progress Committee. (1927). “Progress in the Motion Picture Industry”. Report of the Progress Committee (September): p. 427.

Robach M. (1931) Color in Motion Pictures. James J. Finn Publishing Corp: 1931.

Süddeutsche Zeitung (1928). Süddeutsche Zeitung (September 11): s. 9.

Time Inc. (1926). “Science: Colored Cinema”. Time (August 9): p. 30.

Variety (1931). “Larceny Charge Against Hans Von Frauenhofer”. Variety (December 15): p. 37.

Variety (1936). “$300,000 Suit Over German Color Right”. Variety (August 19): p. 7.

Variety (1937). “Color Patent Suit”. Variety (September 8): p. 6.

Wall, E. J. (1925). 1860-1928: The History of Three-Color Photography. Boston: American Photographic Publishing Company, pp. 164–7.

Patents

Wolff, Emil. Photographische Schicht. German Patent DE000000345734A, filed August 15, 1920, and issued December 17, 1921.

Wolff, Emil. Process for the production of films for cinema recordings. German Patent DE000000371449C, filed April 22, 1921, and issued March 15, 1923.

Wolff, Emil. Production of light-sensitive layers for color photography. German Patent DE000000438616C, filed December 14, 1921, and issued December 21, 1926.

Wolff-Heide, Emil. Procédé pour la réalisation de photographies cinématographiques polychromes. French Patent FR000000609398A, filed January 13, 1926, and issued August 13, 1926.

Wolff-Heide, Emil. Process for the production of color photographic images using layers sensitized with sensitizers in colloidal solution. German Patent DE000000471508C, filed January 7, 1927, and issued February 14, 1929.

Wolff-Heide, Emil. Process for the production of color-sensitive photographic layers. German Patent DE000000607327C, filed August 2, 1928, and issued December 21, 1934.

Wolff-Heide, Emil. Improvements in or relating to processes for the manufacture of light sensitive layers for colour photography. British Patent GB000000340278A, filed September 17, 1929, and issued December 17, 1930.

Fraunhofer, Hans von. Photographic film of the monopack type adapted for color photography. US Patent US2030904A, filed August 3, 1934, and issued February 18, 1936.

Fraunhofer, Hans von. Cinematographic film. US Patent US2067957A, filed December 1, 1934, and issued January 19, 1937.

Friedman, Joseph S. Method for obtaining color separation. US Patent US2047022A, filed May 9, 1935, and issued July 7, 1936.

Friedman, Joseph S., Arthur Bruck. Color sensitive photographic plate and method of producing same. US Patent US2175836A, filed March 11, 1937, and issued October 10, 1939.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Oleksandr Teliuk is a film scholar, archivist and artist. As a film archivist and programmer, he worked at the Dovzhenko Center, Ukrainian State Film Archive. He was co-curator of film programmes and exhibitions at the Film Museum of Dovzhenko Center, including “VUFKU: Lost & Found” (2019); co-editor of books (Cinematographic Revision of Donbas [2017, 2018], Chornobyl (In)Visible [2017] and Ukrainian Film Critic Anthology of the 1920s [2018—2022]); curator of numerous film programmes of Ukrainian archival cinema at international film festivals. He is a graduate of the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation (2024).

Teliuk, Oleksandr (2025). “Wolff-Heide”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.