A subtractive three-color, dye-transfer process, developed at the Chinese Research Institute for Film Science and Technology.

Film Explorer

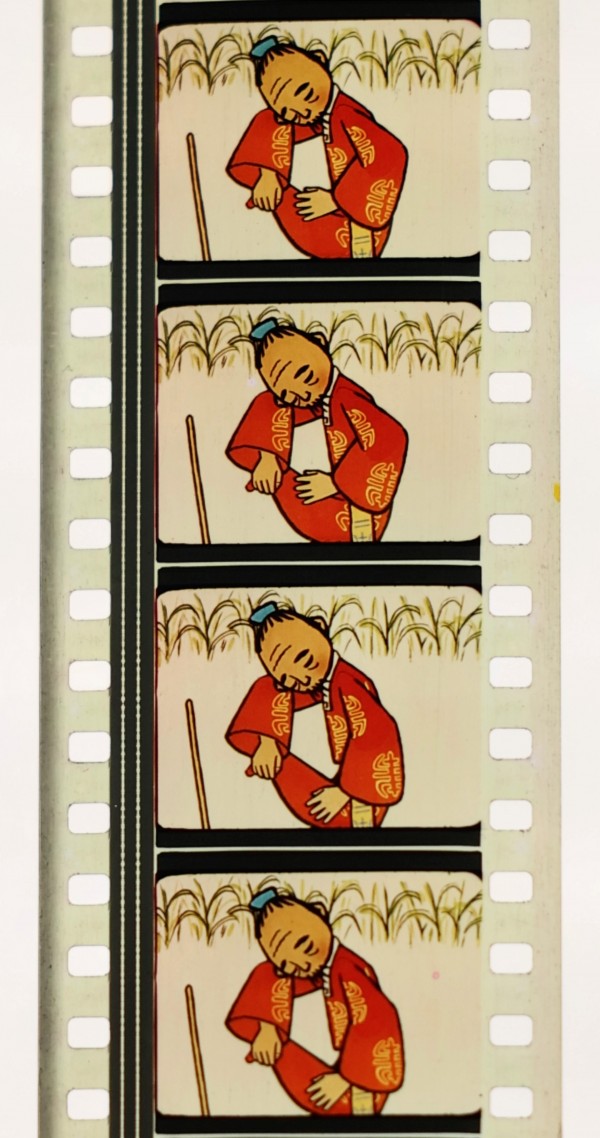

A 35mm dye-transfer print of Yitiao Siyaodai (A Silk Belt) (1961). This print is believed to be on cellulose nitrate stock.

China Film Archive, Beijing, China.

Identification

Imbibition. The cyan, yellow and magenta dyes were transferred in separate passes from dedicated matrix films onto a blank film print.

1

The process was capable of rendering the full-spectrum with high levels of saturation. Prints were made using cyan, yellow and magenta dyes.

None

Optical, silver soundtrack.

Chromogenic color stock (Daidaihong, Agfacolor, Eastmancolor).

History

Dye-transfer or imbibition printing (also known as IB) offered obvious benefits to the Chinese government, whose state-run film industry demanded large print runs, manufactured cheaply, to cover China’s vast geography. Research into a domestic Chinese dye-transfer operation began in 1958, when the government established a specialist research group dedicated to the problem at the Chinese Research Institute for Film Science and Technology (CRIFST) in Beijing (Huang, Miao & Zhang, 1981: p. 8). During the Cold War, as a result of the prevailing climate of Sino–Soviet collaboration, this research was largely based on Russian technical know-how. There were two types of Soviet dye-transfer technology that may have served as a basis for this process – one developed at the Leningrad State Optical Institute, the other developed by Pavel Mershin at Mosfilm in Moscow. Both Soviet technologies shared a distinctive characteristic with the Chinese process – the use of a transfer wheel, instead of a pinbelt (Cavendish, 2016; SMPTE, 1964).

The first iteration of the Chinese process was a prototype named Dongfeng (“East Wind”), which was installed at the Shanghai Film Technology Plant in 1961. Soviet-supplied matrix materials enabled the experimental test printing of animated films shot at the Shanghai Animation Film Studio. The studio did not produce color separations in-camera, but instead used a chromogenic negative stock, which was later filtered to produce discrete color separations. With additional expertise from the Beijing Film Laboratory, the Shanghai Film Technology Plant printed ten copies of the origami animation Yike Dabaicai (A Big Chinese Leaf) in 1962 as part of these early experiments.

The following year CRIFST and the Shanghai Film Machinery Plant designed another prototype, the Huangpujiang II machine (named after a local river), which printed a small number of copies of the paper-cutout animation Yitiao Siyaodai (A Silk Belt). It is unclear how this machine differed from the Dongfeng prototype.

The gradual deterioration of relations during the Sino-Soviet split from the 1960s on, combined with the effects of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) forced the shutdown of CRIFST’s project – doubly condemned for its Soviet influence and perceived ties to the scientific elite. By 1968, under the direction of Jiang Qing (the wife of Chairman Mao), research into dye-transfer printing was transferred to two new teams: one comprising workers of the Beijing Film Laboratory (completely administered and controlled by the Chinese army since July 1967); the other, a cohort of chemical and dye manufacturers, alongside academics, based at the Shanghai Film Machinery Plant and Shanghai Photosensitive Material Plant. Baoding Film Stock plant manufactured blank and matrix stock to support these endeavors.

During the early years of the Cultural Revolution, film production was largely, though not entirely, restricted to cinematic versions of the yangbanxi, or ‘revolutionary model stage works’ –ballets and operas, which were designed to spread Chairman Mao’s communist ideology across China. All yangbanxi featured vibrant color design and were most probably filmed using a combination of Agfacolor stock (imported from East Germany), illicitly imported American Eastmancolor, and Chinese daidaihong stock, manufactured by the Baoding Film Stock plant from 1971 (Pang, 2012; Dootson & Zhu, 2020). This catalyzed renewed interest in improving domestic IB printing. The “First Coordination Conference for the Dye-Transfer Process” was held on February 2, 1969, convening 87 members gleened from 32 institutions across the whole breadth of China. The research into dye-transfer was then escalated into the nationwide Ranyin Fa Dahuizhan (the “Great Pitched Battle for Dye-Transfer Process”). This Dahuizhan resulted in the installation of new, Chinese-made dye-imbibition machines in both Beijing and Shanghai during 1975 – these were used to mass-produce prints of yangbanxi films and some new films such as Huohong de niandai (The Fiery Years) (1974) (Huang, 1995; Shanghai Film Gazette, 1999). It is difficult to tell how different these machines were from earlier iterations, given the propagandistic nature and hyperbole of writing on film technology at the time, which emphasized constant advancement and national self-sufficiency. Later on, American visitors to the Shanghai facility noted the similarity of this equipment to Soviet processes (Samuelson, 1983). The fate of the process after this date is unknown.

Selected Filmography

A live-action feature film produced in the last period of the Cultural Revolution. The staff of a steel plant are in conflict over whether to use domestic materials, or continue importing from the Soviet Union, after the Soviet Union adopts an anti-Chinese position in 1972.

A live-action feature film produced in the last period of the Cultural Revolution. The staff of a steel plant are in conflict over whether to use domestic materials, or continue importing from the Soviet Union, after the Soviet Union adopts an anti-Chinese position in 1972.

Short animation. A moral tale about admitting when you have made a mistake.

Short animation. A moral tale about admitting when you have made a mistake.

Short animation. Adapted from a fable, the film’s story is a moral about work ethics.

Short animation. Adapted from a fable, the film’s story is a moral about work ethics.

Technology

The dye-transfer printing process in Shanghai was modeled on Soviet technology, itself based upon Technicolor’s three-strip process of cinematography and resulting dye-transfer prints. A key difference between Technicolor and this Sino–Soviet system, however, was the use of a transfer wheel rather than a pinbelt. Like Technicolor process Number V, the Chinese process used a chromogenic negative that was subsequently split into color-separation negatives. In China, it is unclear whether matrices were printed directly from the chromogenic camera negative using filters, or whether the negative was first duplicated onto three discrete B/W color-separation positives, before duplicate negatives and matrices were made up.

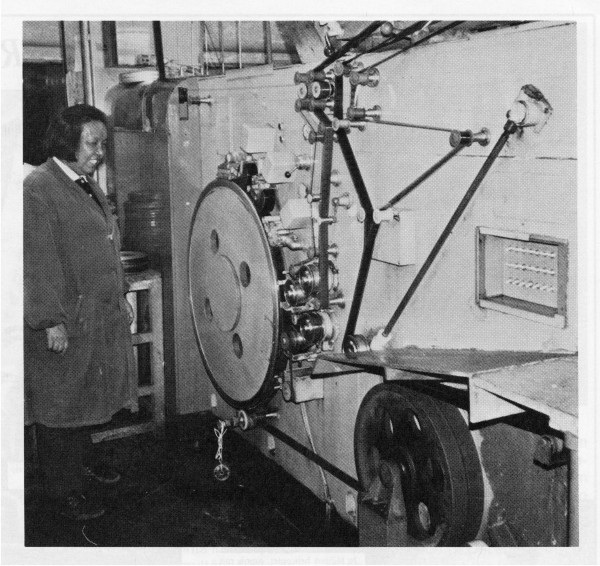

The matrices were developed to harden the gelatin in the most exposed areas of the image. Unhardened gelatin was washed off, leaving a gelatin relief image corresponding to the latent image on the film. Each matrix was passed through a dye-tank in the corresponding complimentary color (the red record was dyed cyan; the green, dyed magenta; and the blue record dyed yellow). A dyed matrix was then held in register with a blank strip on a large, transfer wheel with sprockets, roughly 1m (3.28 ft) in diameter. This enabled the dye to transfer from the matrix to the blank. As the machine had only one transfer wheel (rather than one for each color), the blank had to be run through the machine three times to transfer all the colors (Samuelson, 1983). The dye-transfer process was hailed as a significant technological achievement during the Cultural Revolution in the Communist Party’s media.

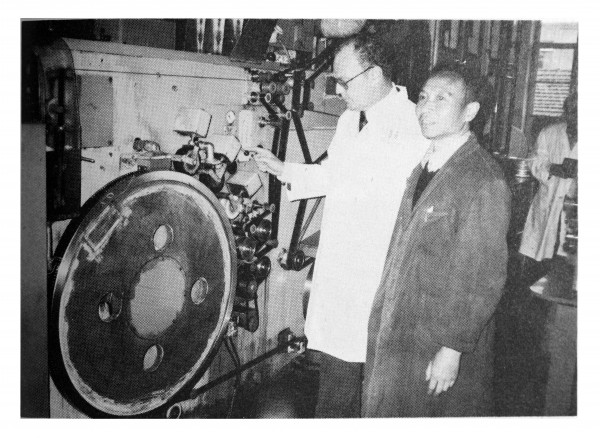

An American Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers delegate and Chinese lab technician discussing the Chinese imbibition process at the Shanghai Film Laboratory, 1979.

W. D. Hedden, F. M. Remley & R. M. Smith (1979). “Motion-Picture and Television Technology in the People’s Republic of China: A Report”. Journal of the SMPTE, 88:9 (September): pp. 610–18.

A Chinese-made imbibition printing machine, at the Shanghai Film Laboratory.

D. W. Samuelson (1983). “Filming in China”. American Cinematographer, 64:5 (May): pp. 25–31.

References

Cavendish, Philip (2016). “Ideology, Technology, Aesthetics, Early Experiments in Soviet Color Film, 1931–1945”. In A Companion to Russian Cinema, Birgit Beumers (ed.), pp.270–291. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Dootson, Kirsty Sinclair & Zhaoyu Zhu (2020). “Did Madame Mao Dream in Technicolor? Rethinking Cold War Colour Cinema through Technicolor’s ‘Chinese Copy’”. Screen, 61:3 (September 1): pp. 343–367.

Huang, Mingzhi, Jinkang Miao & Jian Zhang (1981). Caise Dianying Ranyin Fa (Colour Film Dye-Transfer Process). Beijing: China Film Press.

Huang Mingzhi (1995). “Ranyin fa Caise Yingpian” (“Dye-Transfer Colour Film”). Yingshi Jishu (Film Technology), 5: p. 13.

Pang, Laikwan (2012). “Colour and Utopia: The Filmic Portrayal of Harvest in Late Cultural Revolution Narrative Films”. Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 6:3 (January): pp. 263–82

Samuelson, D.W. (1983). “Filming in China”. American Cinematographer, 64:5 (May): pp. 25–31.

Shanghai Film Gazette (1999). Shanghai dianying zhi (Shanghai Film Gazette). Shanghai: Shanghai shehui kexueyuan chubanshe:p. 533

Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (1964). “Technical Report of a Visit to Motion-Picture Facilities in the USSR”. Journal of the SMPTE, 73:3 (March): pp. 77–195

Yang Haizhou & Feng Shulan (1998). Zhongguo dianying wuzi chanye xitong lishi biannianji (Chronicle of the Chinese Cinema Material Industrial System). Beijing: Zhongguo dianying chubanshe.

Patents

Compare

Related entries

Authors

Kirsty Sinclair Dootson is a Lecturer in Film and Media at University College London. She specializes in the material and technical history of modern color media. Her first book The Rainbow’s Gravity: Colour, Materiality and British Modernity was published in 2023. With Alice Lovejoy and Pansy Duncan she is co-editing the first volume dedicated to the history of film stock and has an essay on Technicolor’s global history in Global Film Color: The Monopack Revolution at Midcentury, Sarah Street & Joshua Yumibe (eds), (Rutgers University Press, 2024.)

Zhaoyu Zhu is a Teaching Fellow in Communication and Cultural Studies at the University of Nottingham, Ningbo, China. He is presently working on his monograph on the production of film technology in the Mao era. He has published articles on Screen and Journal of Beijing Film Academy (Chinese).

Many thanks to Heather Heckman, Lydia Pappas, Laura Major and Philip Cavendish for their assistance with this entry and the comments by the anonymous peer-reviewers.

Dootson, Kirsty Sinclair & Zhaoyu Zhu (2024). “Chinese imbibition prints (CRIFST)”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.