An animation technique that photographed three color records onto one strip of B/W film for printing by Technicolor.

Film Explorer

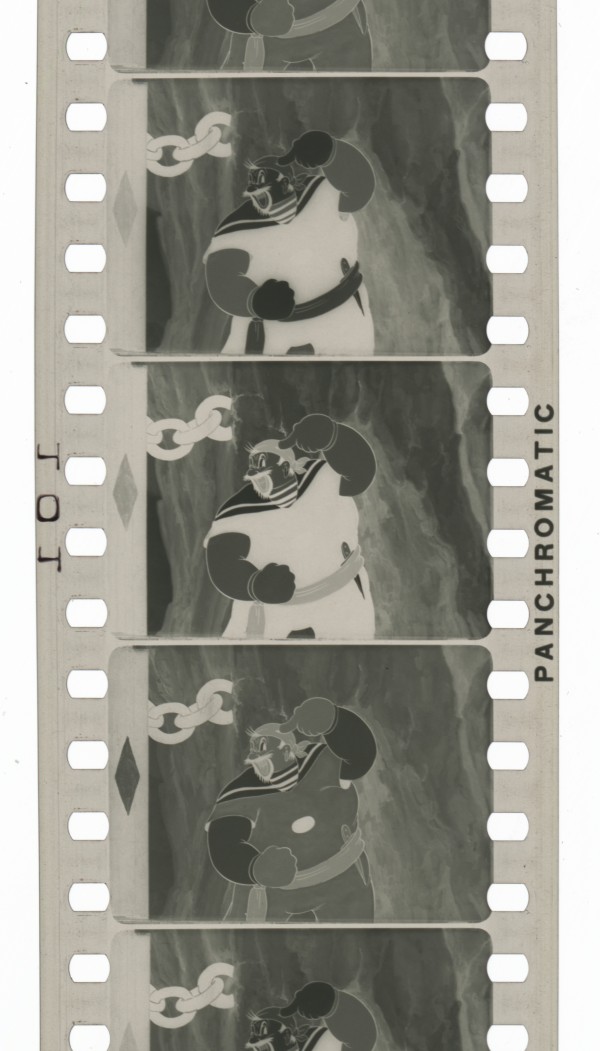

The original successive exposure negative for Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor (1936) by the Fleischer Studios. Color records were captured, one after the next, through blue, red and green filters onto panchromatic B/W stock. Technicolor then recombined these color records with imbibition printing.

Turner Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

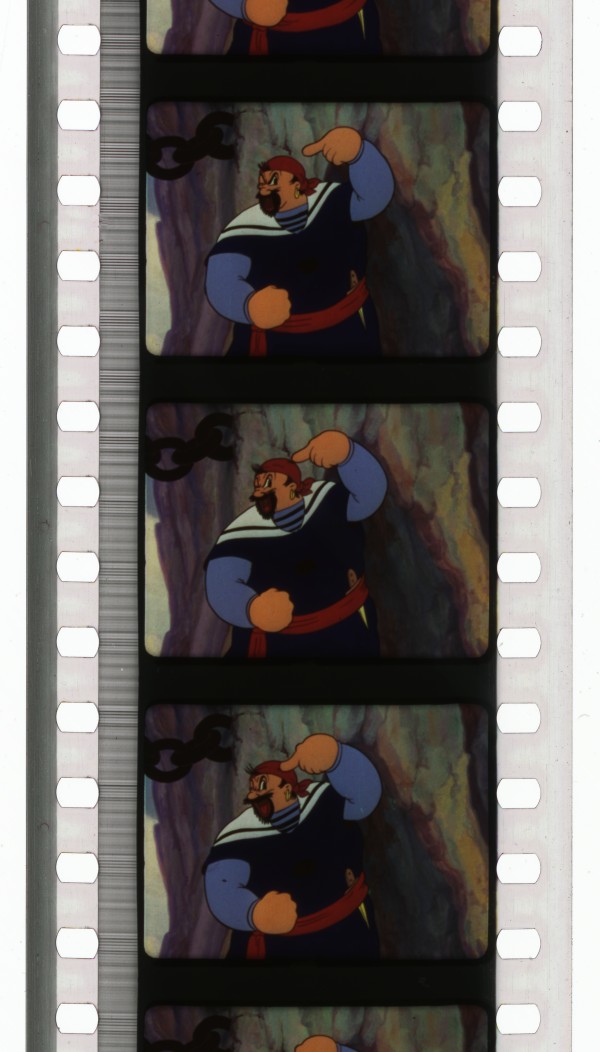

A 35mm nitrate Technicolor print of Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor (1936).

National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, United States.

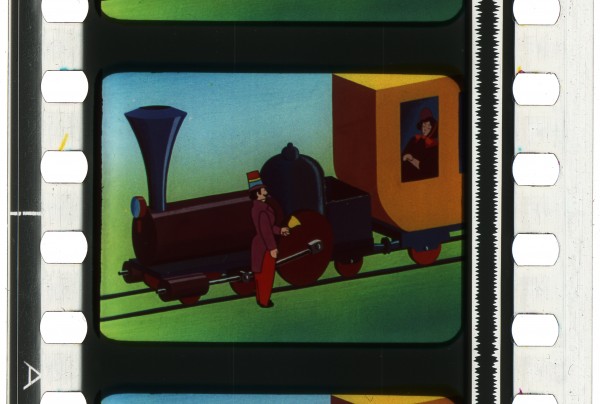

An original Technicolor imbibition print of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) after the separate color records have been recombined. Snow White was the first Technicolor feature photographed using a successive exposure negative. Technicolor prints in the 1930s often featured a subdued palette.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Frame enlargement from a nitrate print of Julius Pinschewer’s Cent ans de chemins de fer suisses (1946). The successive exposure technique was also used widely throughout Europe.

Cinémathèque suisse, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Identification

Academy standard: 20.95mm x 15.24mm (0.825 in x 0.600 in).

1.37:1 for prints from 1935 to c.1953; thereafter, different widescreen formats and aspect ratios were used.

Technicolor imbibition. Three dye records transferred onto blank film from matrix stock.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge print. Some European negatives and prints may have Agfa or Ferrania edge markings.

1

Three colors imbibition on blank stock, subdued colors (early Technicolor).

Color by Technicolor.

Mostly variable-area or variable-density. Some 1950s prints may have magnetic stripe soundtracks.

Typically Movietone (20.98mm x 17.98mm / 0.826 in x 0.708 in) or Academy (22.05mm x 16.03mm / 0.868 in x 0.631 in) standards.

4 perforation, vertical for each frame; however, three frames (12 perforations) are used on the negative for each final frame on the film print.

Panchromatic B/W negative capturing red, green and blue color records onto separate successive frames.

History

Technicolor’s three-color process was first used in 1932. Thanks to a new camera, patented by Technicolor’s Joseph Arthur Ball and Gerald F. Rackett, the full spectrum of colors was captured through red, green and blue filters onto three separate B/W negatives. Although ultimately intended for live action photography, some of the first three-color Technicolor releases were animations, beginning with Walt Disney’s Flowers and Trees (1932). Technicolor’s “C camera” was initially used to photograph cartoons during the period 1932 to approximately 1936. The “C camera” featured a flexible drive shaft which could be adapted for single-frame photography for animation, or making titles. Three of these cameras were made (C-1, C-2 and C-3), but were largely phased out, except for making titles, when Technicolor’s “D camera” series for live action was introduced, beginning in 1933. Camera C-1 was assigned to Disney, although it remained on Technicolor property in Hollywood and had to be supervised by Technicolor personnel. Three-color photography continued through The Sorcerer's Apprentice segment (1937) ultimately placed in Fantasia (1940). The Oscar winning The Old Mill (1937) appears to have been Disney’s final three-color camera production.

From about 1935, several animation production companies started using successive exposure photography. This may have started with the Fleischer Studios in New York with several two-color Technicolor productions. (According to Technicolor’s records, the two-color cartoon An Elephant Never Forgets [1935] was successive-exposure). A single B/W negative system with three successive exposures was preferred since it made the shooting of animation films much easier. By contract, Disney owned an exclusivity on the three-color process for three years. Once this expired, other animation producers like Leon Schlesinger (for Warner Bros.), Max Fleischer (Paramount), Walter Lantz (Universal) and Charles Mintz (Columbia), among others, adopted successive exposure photography with Technicolor release prints. For instance, The Merry Melody Flowers for Madame, directed by Friz Freleng and produced by Leon Schlesinger for Warner Bros., can be considered among the first successive exposure shorts since it was released in 1935.

According to the inspection of original elements, the earliest known Disney short photographed in successive exposure was Donald's Ostrich (released December 10, 1937). Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which started production in 1935, was the first successive-exposure feature. The use of subdued colors in original Technicolor release prints contributed to the success and enchantment of this adaptation of the Brothers Grimm fairy tale. After 1955, successive-exposure photography on some films was modified to be compatible with new widescreen formats. Sleeping Beauty (1959), for instance, was shot in Technirama, using a horizontal successive-exposure system with each frame eight perforations wide.

Robin Hood (1973) appears to be the last Disney feature photographed using successive exposure and printed in dye-transfer prints, but the successive-exposure technique continued for animation photography for many years, albeit with Eastmancolor release prints. Oliver & Company (1988) was the last Disney feature photographed entirely using successive exposure. The Little Mermaid (1989) was started as a successive-exposure production, but this method was abandoned midway through in favor of Eastmancolor negative. The film was the first Disney animated feature in 50 years not shot using successive exposure. Some later Disney productions made with digital intermediates were output to 35mm successive-exposure negative for preservation.

Selected Filmography

A successive-exposure Technicolor feature made in the UK.

A successive-exposure Technicolor feature made in the UK.

A rare successive-exposure Technicolor animation made in Switzerland, processed in the British Technicolor laboratory.

A rare successive-exposure Technicolor animation made in Switzerland, processed in the British Technicolor laboratory.

Considered the first three-color short made by Disney using successive exposure photography.

Considered the first three-color short made by Disney using successive exposure photography.

One of the earliest documented successive exposure Technicolor shorts.

One of the earliest documented successive exposure Technicolor shorts.

A silhouette film made in Technicolor.

A silhouette film made in Technicolor.

The first Popeye cartoon produced in Technicolor.

The first Popeye cartoon produced in Technicolor.

A production mixing B/W and three-strip Technicolor live-action footage, alongside successive-exposure animated scenes.

A production mixing B/W and three-strip Technicolor live-action footage, alongside successive-exposure animated scenes.

Possibly the last feature photographed using successive exposure and released with Technicolor prints.

Possibly the last feature photographed using successive exposure and released with Technicolor prints.

An Italian feature that might have used successive exposure photography. It was processed in the British Technicolor laboratory.

An Italian feature that might have used successive exposure photography. It was processed in the British Technicolor laboratory.

Photographed horizontally on 35mm film using the Technirama format and successive exposure. Released in 35mm Technicolor prints and in 70mm Eastmancolor Super Technirama prints with a six-track stereo sound and a 2.20:1 aspect ratio.

Photographed horizontally on 35mm film using the Technirama format and successive exposure. Released in 35mm Technicolor prints and in 70mm Eastmancolor Super Technirama prints with a six-track stereo sound and a 2.20:1 aspect ratio.

The first feature length production made using successive exposure photography.

The first feature length production made using successive exposure photography.

Technology

Successive exposure allowed animators to shoot a color image on B/W film frame-by-frame. The process used a “regular” camera loaded with a single roll of Eastman supersensitive panchromatic B/W negative with standard Bell & Howell perforations. Each animation set-up was automatically exposed on three separate frames of film – one after the other – each frame registering one of the primary colors of the Technicolor process. A revolving filter wheel was synchronized to the shutter shaft of the camera and was fitted with three filters – a blue filter which registered the yellow-printing values, a red filter for the cyan-printing values and a green filter for the magenta-printing values (Wratten filters #47, #25 and #58). The filter wheel was timed to first expose a frame through a blue filter, then the red in 2nd position and finally the green in 3rd position on the negative. Any ordinary B/W camera could be converted for successive-exposure Technicolor simply by adding the filter-wheel. A Bell & Howell 2709 camera was used to shoot most of Disney’s color animated films from 1937 until the end of the system in 1989.

Using a standard camera for successive exposure gave more control to the producer. It undoubtedly made it possible to have a lighter and more ergonomic camera for shooting animated films, simplifying camera operation and processing because only a single negative was used. Walt Disney's Multiplane system, for instance, required placing the camera in a high-up vertical position directed downward toward the cells, photographing through multiple glass plates of painted scenery to give the illusion of depth in the image. Producers were able to use their own cameras and operators, but the processing and editing of the negative was done by Technicolor. Technicolor also provided the raw negative stock as part of a contract.

Unlike with three-strip Technicolor live-action photography, the three successive exposure negative records were all on the same film strip, making it impossible to process each of the colors at a unique gamma. As a result, the paints used on the animation cells did not reproduce accurately in Technicolor prints; they displayed with more contrast and the colors shifted from the desired result. This forced the studios (Disney in particular) to develop what was called the “SE Paint Palette.” This required cells to be painted essentially in false colors, with a lower-contrast “flatter” look, to ensure that colors would yield the desired color and contrast in the final release prints.

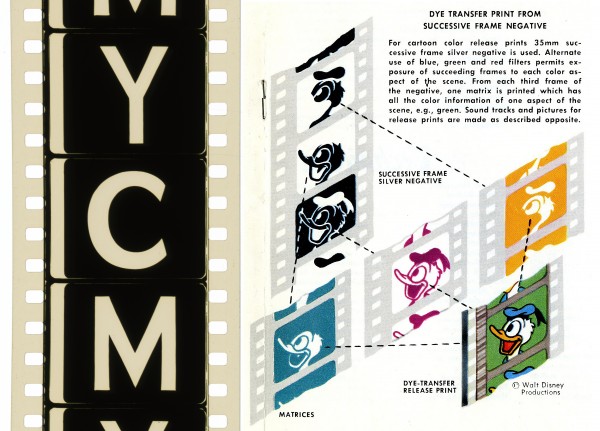

Since the shooting was made by stop crank, arc lights could not be used since they varied in density and fluctuated. Mazda lights were instead recommended, even though an extra blue filter was needed on the lens to correct the color temperature. The system was not suitable for shooting live action, due to the exposure time of each frame, which was slower for animation. To recreate a Technicolor IB print, it was necessary to separate the three color records from the single negative and print them separately on three matrices – yellow, cyan, and magenta (YCM).

Left: Yellow (Y), cyan (C) and magenta (M) frames marked on the leader for a successive-exposure negative.

Right: How dye transfer prints were made from successive exposure negatives.

Left: Turner Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Right: Anon., April 1955. “Current Techniques of 35mm Color Motion Picture Printing”. Technicolor News and Views, XVII.

References

Anon. (1948). Interrogatory No. 4 – Supplement [List of all Technicolor contracts]. United States v. Technicolor, Inc., Technicolor Motion Picture Corp., and Eastman Kodak Co., Civil Action No. 7507-WM (S.D. CA 1947), National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, United States.

Anon. (1955). “Current Techniques of 35mm Color Motion Picture Printing”. Technicolor News and Views, XVII:1 (April): p. 4.

Anon. (Undated). Technicolor 3-Strip Cameras. Technicolor Corporate Archive, George Eastman Museum, NY, United States.

Ball, Joseph A. (1935). The Technicolor Process of Three Color Cinematography. Hollywood, CA: Academy Technicians Branch.

Cave, George A. (1935). Letter to Edward Nassour, August 23. United States v. Technicolor, Inc., Technicolor Motion Picture Corp., and Eastman Kodak Co., Civil Action No. 7507-WM (S.D. CA 1947), National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, United States.

Fallberg, Carl (1942). “Animated Cartoon Production Today, Part V, Painting, Photographing, and Re-Recording”. American Cinematographer, 23:8 (August): pp. 344–346.

Fleischer, Max & Frederick F. Bryant (1936). Agreement between Fleischer Studios Inc. and Technicolor Motion Picture Corporation, June 1, 1936. United States v. Technicolor, Inc., Technicolor Motion Picture Corp., and Eastman Kodak Co., Civil Action No. 7507-WM (S.D. CA 1947), National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, United States.

Iwerks, Don (2019). Walt Disney’s Ultimate Inventor, The Genius of Ub Iwerks. Los Angeles, CA: Disney Editions.

MacQueen Scott (1994). “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: Epic Animation Restored”. The Perfect Vision, 22: pp. 26–31.

Stewart, Jez (2021). The Story of British Animation. London: British Film Institute/Bloomsbury.

Patents

Ball, Joseph A. and Gerald F. Rackett. 1931. Cinematographic Camera, US Patent 2,072,091, filed August 20, 1931, patented March 2, 1937.

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Authors

Céline Ruivo is the author of a 2016 PhD dissertation titled The Three-color Technicolor: History of a Process and Challenges of its Restoration, University Paris III la Sorbonne nouvelle. She worked as the head of the film collection of La Cinémathèque française from 2011 to 2020. She is an active member of the technical commission of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). She is now a post-doctoral researcher for the B-Magic project at UCLouvain in Belgium.

James Layton is a film historian and archivist specializing in the history of motion picture technology. He is Manager of The Museum of Modern Art’s Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center, and is co-author of two books with David Pierce: The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (2015) and King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue (2016). Prior to working at MoMA, Layton was an archivist at George Eastman Museum, where he curated two gallery exhibitions celebrating CinemaScope and Technicolor, and the informational website Technicolor 100. He was project manager of the East Anglian Film Archive’s digital film archive and website relaunch in 2011, and also contributed to the Image Permanence Institute’s Knowing and Protecting Motion Picture Film informational poster (2010). More recently, he contributed a significant chapter on Eastman Kodak to FIAF’s expanded edition of Harold Brown’s Physical Characteristics of Early Films as Aids to Identification (2020).

The authors would like to thank Jez Stewart (BFI), Caroline Fournier (Cinémathèque suisse) and Theo Gluck for their contributions, as well as the knowledgeable peer reviewers.

Ruivo, Céline & James Layton (2024). “Technicolor Successive Exposure”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.