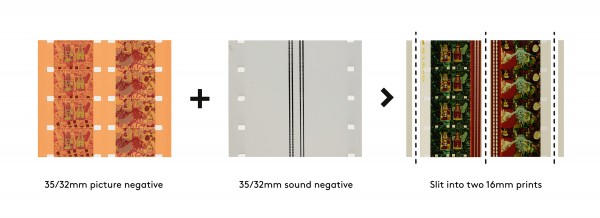

35mm and 32mm-wide duplicating and print stocks that were used to mass produce 16mm prints. After printing and processing, the film was slit to create two 16mm prints.

Film Explorer

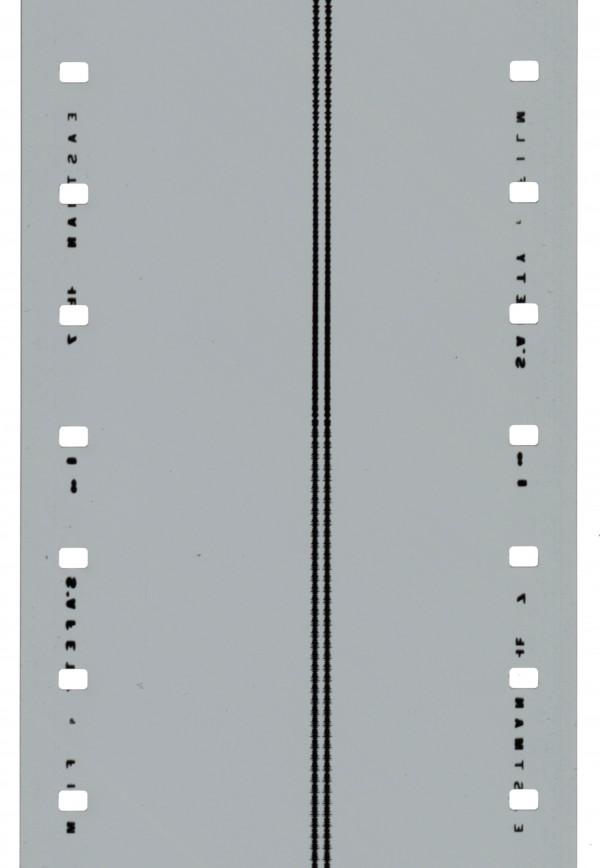

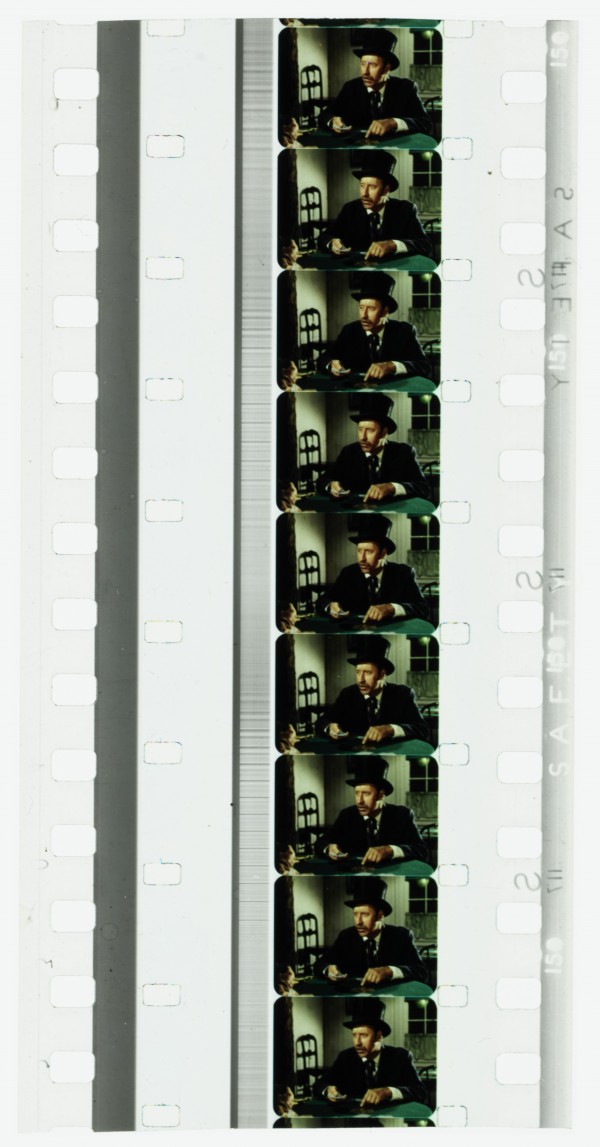

The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959). 35/32mm variable-area soundtrack negative for making 16mm prints. This film is 35mm wide, but has 16mm perforations.

Russ Meyer collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

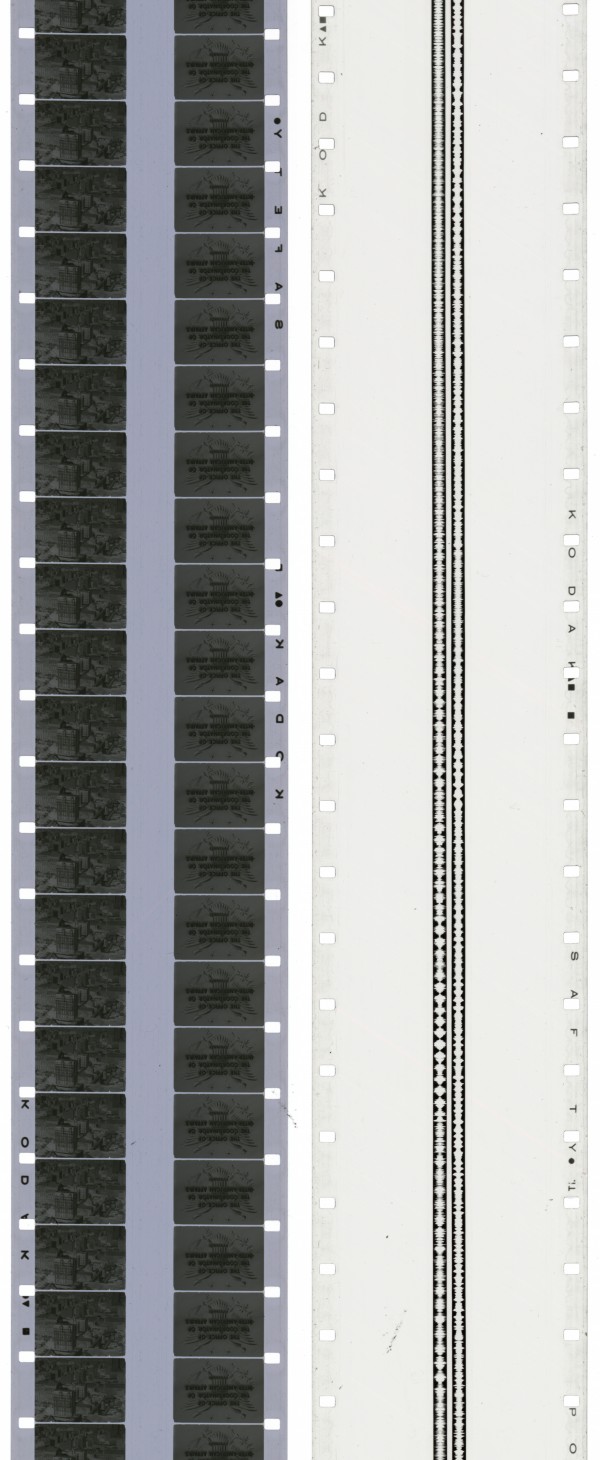

Separate picture and sound printing negatives for São Paulo (1944) on 32/16mm stock (32mm wide). These elements were made from 35mm master elements at Precision Film Laboratories in New York in 1944 via two passes in the printer to create one complete copy on the left side of the film, and another complete copy running in the opposite direction on the right side. The Eastman Kodak dating symbols reveal the stock dates to 1943.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

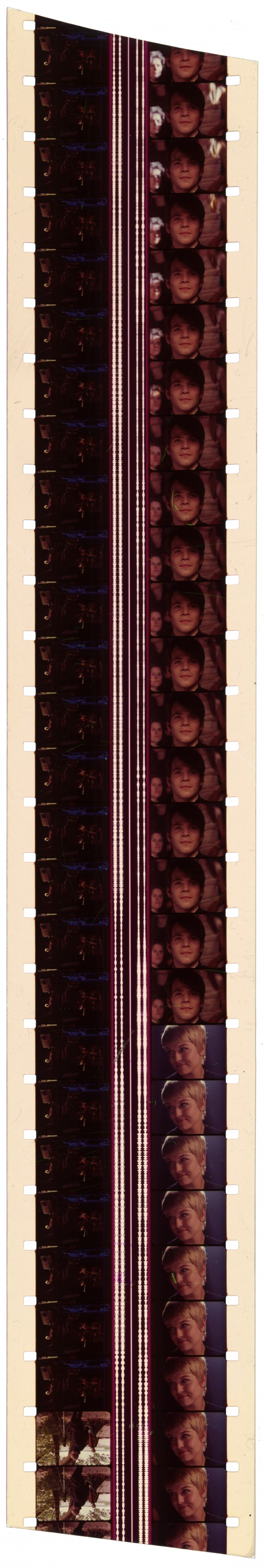

Backbeat (1994). 35/32mm film print before being slit into two 16mm prints. In addition to being cut down the middle, 1.5mm of blank film had to be trimmed off each outside edge.

Theo Gluck, Studio City, CA, United States.

Identification

Prints were made on film 32mm-wide, then were slit into 16mm prints for projection.

Two rows of 16mm long-pitch standard 16mm print perforations.

(after slitting to 16mm)

Color or B/W.

According to one source from 1954, Eastman Kodak 32mm film carried a dot after the word “SAFETY”, appearing thus: “KODAK SAFETY ● POSITIVE”.

Possibly, but rarely, on cellulose nitrate before 1950.

1

Eastmancolor and other compatible emulsions. Some examples from before the 1980s now likely show signs of color fading.

None

Depending on the original sound, either variable-density or variable-area.

16mm frame dimensions. Approximately 10.26mm x 7.49mm (0.403 in x 0.295 in). Two rows of images on 35mm film.

Two rows of 16mm short-pitch standard perforations.

Color or B/W for picture negatives; B/W for sound negatives.

Standard 16mm edge markings and placement.

History

Until the introduction of 16mm film in 1923, the most common film width was 35mm. Most major laboratories at that time only had equipment to print and process 35mm film. As 16mm became more popular and demand for feature films in 16mm increased in the 1930s, Etablissements André Debrie in Paris, France devised the 35/32mm printing process which used 35mm film with two rows of 16mm perforations, 32mm apart. A similar process used 32mm-wide film with 16mm perforations. These negatives allowed two prints to be made simultaneously before being slit into individual prints.

Until 1950 there were no recognized standards for 35/32mm or 32/16mm film stock. Debrie realized that the slitting process in laboratories did not have the film manufacturers’ precision; if the film was not slit exactly in half, then one of the 16mm films would be oversize and possibly jam in the projector. Debrie therefore decided to make the 32mm film undersize to 31.8mm. US manufacturers made film to this width but eventually altered it to 31.9mm. The reduction in width ensured that if the slitting wasn’t accurate then one print would not be oversized with the potential to become caught in the projector. This continued until the 1950 SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) standards for 32mm negative and positive and 35/32mm stocks were issued. Up to that point there were four or five slightly different styles of perforating in use at various times. The new standard reduced the width of the 32mm film by 0.001" to 31.93mm. (Standards Editorial 1951). There were no new standards issued for 35/32mm stock as the standards committee were concerned that 35mm nitrate with 16mm perforations could be slit to make 16mm nitrate film and used at home with the attendant danger of domestic fires. (The 16mm format was specifically developed to only use “safety” or acetate film).

Technicolor used a related, but different, system for making 16mm prints. The company was only able to process 35mm perforated film using its imbibition process, so it first printed a 16mm image down the center of a 35mm film and then re-perforated the 35mm with 16mm perforations before slitting. This was called “single rank printing”. For a relatively short period of time, from approximately 1963 to 1971, Technicolor also made “double rank” 16mm imbibition prints on 35mm stock, similar to conventional 35/32mm printing.

In the mid-1970s, Technicolor phased out its imbibition printing and switched to standard Eastmancolor negative and print stocks to mass produce 16mm and 8mm prints of feature films. Technicolor’s optical printer reduced 35mm interpositives to either 16mm or 8mm 35/32mm printing negatives while simultaneously performing pan-and-scan cropping on widescreen films. For 8mm reductions (either Standard 8mm or Super 8), four rows of images were printed on 35mm film. After prints were slit to 16mm or 8mm, 3mm of waste film was discarded.

Many commercial laboratories offered this service well into the 1990s or later. Although these methods appear to be no longer in use, Eastman Kodak continues to offer 35mm film with multiple rows of 16mm and 8mm perforations in its current sales catalogues.

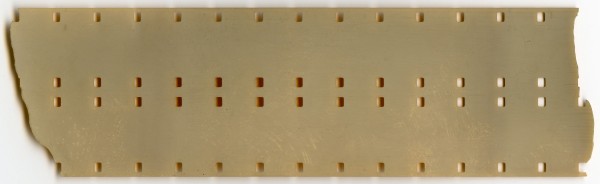

A sample of 32mm film made by André Debrie in the 1930s. It contains four rows of 16mm perforations and, after printing, would have been slit into two silent, double-perforated 16mm prints.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

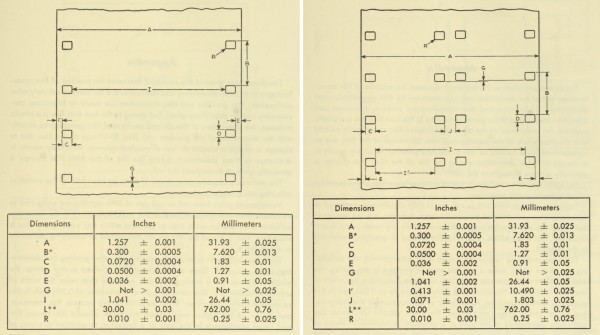

Left: Proposed American Standard Cutting and Perforating Dimensions for 32mm Sound Motion Picture Negative and Positive Raw Stock, Z22.71, December 1948.

Right: Proposed American Standard Cutting and Perforating Dimensions for 32mm Silent Motion Picture Negative and Positive Raw Stock, Z22.72, December 1948.

Anon. (1951). “American Standard PH22.72-1950”. Journal of the SMPE, 56 (1951): pp. 239, 240.

A 16mm single rank, Technicolor dye-transfer print of Anthony Mann’s Bend of the River (1952) on 35mm film. After printing, the edges would have been slit to produce a single 16mm print.

Kodak Collection, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Selected Filmography

16mm prints were made from a 16mm picture negative and a 32/16mm soundtrack negative.

16mm prints were made from a 16mm picture negative and a 32/16mm soundtrack negative.

An anti-drug, educational film. 16mm prints were made from 35/32mm picture and soundtrack negatives.

An anti-drug, educational film. 16mm prints were made from 35/32mm picture and soundtrack negatives.

This is one of the most recently produced films with identified 16mm prints that was made using 32/16mm picture and sound negatives.

This is one of the most recently produced films with identified 16mm prints that was made using 32/16mm picture and sound negatives.

16mm prints were made from a 16mm picture negative and a 35/32mm soundtrack negative.

16mm prints were made from a 16mm picture negative and a 35/32mm soundtrack negative.

This film was printed at Precision Film Laboratories in New York. 16mm prints were made from a 32/16mm picture negative and a 32/16mm soundtrack negative.

This film was printed at Precision Film Laboratories in New York. 16mm prints were made from a 32/16mm picture negative and a 32/16mm soundtrack negative.

Technology

Paramount described in 1949 its method for producing 16mm release prints from 35mm originals using 35/32mm and 32/16mm stocks.

A specially-designed optical printer was used to make a “double-track” picture negative (two rows of 16mm frames), and a specially-designed sound recorder produced a “double-track” sound negative, both using 35mm stock with 16mm perforations (35/32mm). Then, a specially-designed contact printer was used to print two 16mm prints onto 1,200-ft rolls of 32mm-wide film with 16mm perforations (32/16mm), which was subsequently processed on a processing machine adapted for 32mm film. The 32mm stock produced 3,000 ft of 16mm print after the 32mm film was slit.

The 35/32mm “double track” sound negative was made by re-recording from a normal, combined release print and the 35/32mm “double track” picture negative was made from the existing master fine-grain positive, or interpositive. The picture negative and the sound negative were printed and recorded in two passes, with the first pass run from ‘head to tail’, and the second pass running in the opposite direction.

The 35mm masters were never slit. Before 1950, these masters were usually printed on cellulose nitrate stock and slitting these could have led to flammable 16mm nitrate films becoming available to non-professionals and the domestic market.

The advantage of the 35/32mm and 32/16mm systems was that normal 35mm equipment could mainly be used, providing an economic means of producing bulk 16mm prints.

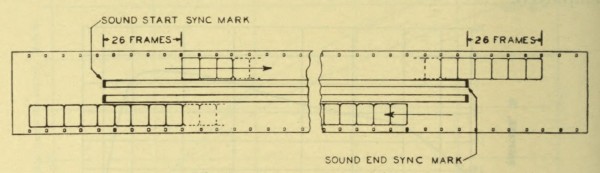

32/16mm release print, before being slit into two 16mm prints. One copy ran in one direction, while the other copy ran in the opposite direction.

La Grande, Frank, C. R. Daily & Bruce H. Denny (1949). “16 mm Release Printing Using 35- and 32-mm Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 52 (February): p. 218.

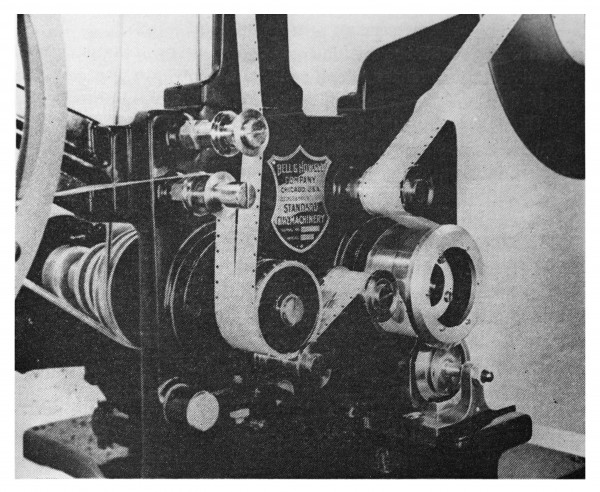

The specially designed Bell & Howell slitter used by Paramount Pictures in the 1940s to cut 32mm print stock into two 16mm prints.

La Grande, Frank, C. R. Daily & Bruce H. Denny (1949). “16 mm Release Printing Using 35- and 32-mm Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 52 (February): p. 221.

The original 35/32mm picture and sound printing negatives, and resulting 16mm prints, for Curious Alice (1971). 1.5mm of waste film on either edge on the print film was discarded after slitting.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, United States. Diagram by Oleksandr Teliuk.

References

Anon. (1951). “Cutting and Perforating 32-mm Film” (Standards Editorial). Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 56:2 (February): pp. 235–240.

Hollywood Film Co. (c. 1970). “Precision Film Slitters”. Hollywood Film Company (Sales Catalog), pp. 65–66. Hollywood, CA: HFC Co.

La Grande, Frank, C. R. Daily & Bruce H. Denny (1949). “16 mm Release Printing Using 35- and 32-mm Film”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 52 (February): pp. 211–222.

Eastman Kodak Company (2023). Motion Picture Products Price Catalog for the United States. https://www.kodak.com/content/products-brochures/Film/Kodak-Motion-Picture-Products-Price-Catalog-US.pdf (accessed November 17, 2023).

Robertson, A. C. (1954). “Evaluation of the Steadiness of 16mm Prints”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 62:4 (April): pp. 265–270.

Spilker, Eric (2024). “History of 16mm Technicolor Printing”. https://www.paulivester.com/films/filmstock/tech.htm (accessed March 13, 2024).

Related entries

Author

Brian Pritchard began his career at the Kodak Research Laboratories in 1962, working on X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis, followed by measuring Modulation Transfer Function of Films. He then moved to the Motion Picture Sales Department as a technician. In 1969, Pritchard moved to Filmatic Laboratories where he became Technical Director, moving to Humphries Laboratories in 1981 as Technical Director; and then in 1987 moved to Hendersons Film Laboratories. Brian became a consultant in 2002, including a number of years at the National Film Archive. He is the co-author of a book with David Cleveland, How Films Were Made and Shown: Some Aspects of the Technical Side of Motion Picture Film 1895–2015 (2015) and a contributor to the expanded edition of Harold Brown’s Physical Characteristics of Early Films as Aids to Identification (2020) and to the Journal of Film Preservation.

Pritchard, Brian (2024). “35/32mm and 32/16mm perforated film”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.