Film Explorer

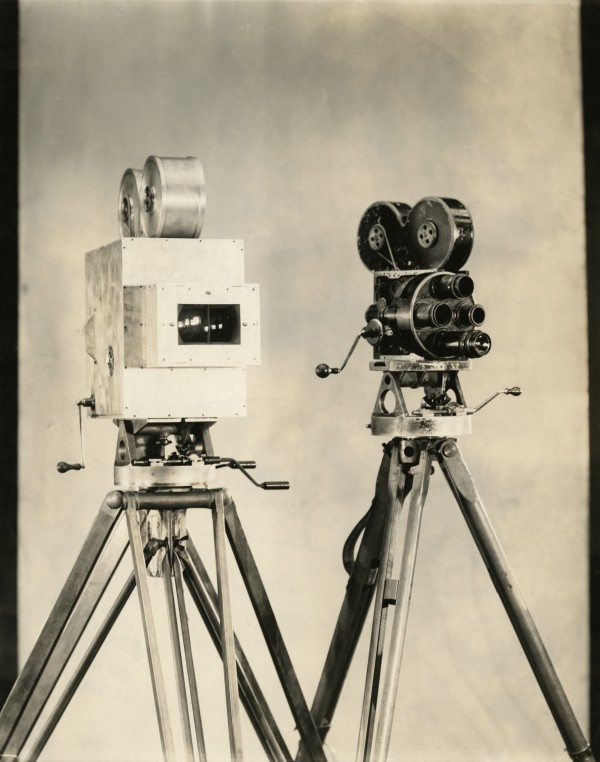

Robert Armstrong and Jean Arthur in RKO’s Danger Lights (1930). The mute 63.5mm-wide film was synchronized with a soundtrack printed on a separate 35mm film strip

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

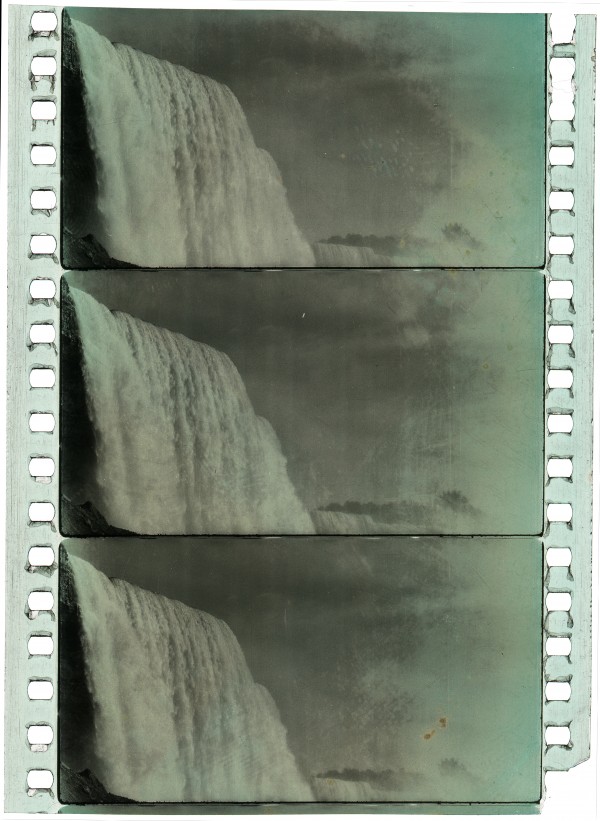

A 63.5mm frame from one of the two Niagara Falls demonstration shorts made in Natural Vision (1925). The gelatin emulsion layer on this B/W print is tinted blue. A twin-lens camera was used to film the image, creating a greater depth of field, which at the time was described as stereoscopic.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

Approx.

History

Natural Vision was a large-format widescreen process that was presented in different forms over the years, as its technology evolved. Initially envisioned as 3-D or stereoscopic, the Natural Vision camera utilized two lenses to capture a greater depth of field onto one film frame. Despite numerous trade screenings, adoption by a major Hollywood studio, and two high-profile feature films produced over its 20-year development, the format’s prospects of widespread adoption remained limited. Plagued by poor management, limited investment, a string of bad luck, and the format’s reliance on special cameras and projectors meant Natural Vision stood slim chance of succeeding in an industry already committed to 35mm production and distribution.

Natural Vision was the brainchild of Swedish inventor Per Johan Berggren, an electrical and mechanical engineer, originally from Stockholm. Berggren approached George K. Spoor with his invention in 1916 – which he claimed produced stereoscopic results – and convinced the co-founder of the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company to finance the development of a prototype camera. Spoor believed strongly enough in the possibilities of Berggren’s design that he purchased the interest of his Essanay partner, G. M. Anderson, ceased further production at the Essanay studio in Chicago, and transformed his properties into a motion picture research laboratory. Tests with the new camera were reportedly made on one scene of Young America in 1918 (Anon., 1918).

By 1923, Spoor and Berggren had spent over US$1,500,000 and had redesigned the camera multiple times. The earliest tests had been with 35mm film, but due to definition problems, the film’s width was increased to 63.5mm (2.5 in), which necessitated all-new camera and projection equipment. This new film, with a frame six-perforations high, instead of the normal four with 35mm film, created a wider than normal image, with an aspect ratio varying over the years between 1.85:1 and 1.95:1. The first press screening of this new system was held at the old Essanay film studios in Chicago on August 18, 1923, onto an enlarged screen measuring approximately 40 ft x 20.5 ft (12.2m x 6.2m). The specially designed screen apparently enabled the actors to stand out in relief from the background, creating depth (Anon., 1923).

Spoor announced commencement of a self-produced feature in 1925, based on Margaret Hill McCarter’s The Pride of the Prairie, but severe storms destroyed the film’s sets on location in South Dakota and the film was abandoned. Two years later, Spoor did succeed in filming The Flag Maker in Natural Vision. The feature was shot in Hollywood, starred Charles Ray and Bessie Love, and was directed by stalwart J. Stuart Blackton. Four Natural Vision cameras, each weighing 200 lb (91kg), were brought down from Chicago for the production. The film was to premiere at the newly opened Roxy Theatre in Manhattan, but it missed its announced premiere date and was later shelved and destroyed. Spoor was reportedly deeply disappointed in the picture, believing that it did not do the Natural Vision process justice (Anon., 1927).

In 1929, Spoor and Berggren signed a contract with RKO Radio Pictures following a successful Photophone synchronized sound test. This deal came at a time when most of the major Hollywood studios were exploring widescreen or large-format processes following the Fox Film Corporation’s ambitious plans with Fox Grandeur. RKO made the short Campus Sweethearts, featuring Rudy Vallee and Ginger Rogers, as a production test in 1929, and the studio’s first Natural Vision feature followed in November 1930 with Danger Lights. The railroad drama premiered at the State-Lake Theater in Chicago before moving to the Mayfair Theatre in New York a month later. The State-Lake projectors had to be removed and reinstalled in New York as they were the only working pair in existence. Audiences at the time did not embrace widescreen, and RKO chose not to continue its contract with the Spoor-Berggren process (Kahane, 1930).

Undeterred, George K. Spoor revived Natural Vision once again at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. At a cost of $150,000, a specially designed 1,250-seat auditorium named Spoor’s Spectaculum was constructed on Northerly Island, on Chicago’s Lake Michigan lakefront, with an enormous screen measuring 64 ft x 38 ft (19.5m x 11.6m). But the venture was unsuccessful, and the Spectaculum attraction did not return for the World Fair’s second year in 1934. Spoor subsequently defaulted on his loans, was forced to close his Argyle Street studios in Chicago, and soon after, Natural Vision Pictures, Inc. was dissolved.

Selected Filmography

Unreleased feature film based on Jewel Spencer’s The American.

Unreleased feature film based on Jewel Spencer’s The American.

Short demonstration film screened in revised forms in 1925, 1929 and 1933. Also known as Niagara Falls, Spectacle of the Mighty Cataracts.

Short demonstration film screened in revised forms in 1925, 1929 and 1933. Also known as Niagara Falls, Spectacle of the Mighty Cataracts.

Technology

It’s hard to precisely track the early technological development of the Natural Vision large-format process as initial reports are sparse, unrevealing, and often contradictory. It appears that the camera, film and projection equipment changed many times between 1916 and 1933, with the initial intention to create a 3-D projection experience on a split-screen – later becoming a large-format widescreen process with increased depth of field.

Per Johan Berggren’s initial invention, which was tested in 1918, used standard 35mm film in a specially designed camera with two lenses side-by-side and a complex internal optical system. Two images, slightly offset in angle and focus, were captured through the twin-lenses and blended together on the film strip. It was claimed this created film objects with more rounded edges and a greater depth of field overall. A 1921 report in the New York Times suggested that any standard camera or projector could be converted to this process with the addition of a small attachment (Anon., 1921).

By 1923, the Natural Vision process was using film 63.5mm wide. The new camera, which still used the same principle of superimposing one image on top of another, was reportedly four times as large as a standard motion-picture camera. Its twin-lenses had a parallax of three inches, approximately that of the human eyes. A special split-screen was also required, in which lines of black thread were used to create a “breaking surface” or curtain in front of an opaque screen behind. The projected image therefore appeared to float in front of the background. It was claimed this image could be viewed from any angle without distortion. By 1925, this double-screen approach appears to have been abandoned.

In 1929, the Natural Vision process was adapted for use with synchronized sound. The camera was redesigned and reduced in weight from 200 lb to 85 lb (90.7kg to 38.6kg) (Reeves, 1929). The twin-lens system now used 13 optical members to resolve the two images into a single picture. The combined image contained “dual shadows”, which, when projected, lent a roundness and depth to the scene. The 63.5mm projector used a stream of compressed air to steady the movement of the film and eliminate vibration, bending the film in the aperture to maintain consistent focus across the full width of the screen (Anon., 1929). Because of the enlarged projected image, the screen was coated with finely-beaded glass to maintain picture brightness.

References

Anon. (1918). “Spoor’s New Camera”. Variety, July 26, 1918: p. 35.

Anon. (1921). “Screen: People and Plays”. New York Times, January 23, 1921.

Anon. (1923). “Spoor Gives Showing of New Movies”. Chicago Daily Tribune, August 21, 1923: p. 15.

Anon. (1927). “Spoor Takes $150,000 Loss When He Discards Third Dimension Picture”. Exhibitors Herald, October 1, 1927: p. 20.

Anon. (1929). “First Demonstration of Sound Motion Pictures in Lifelike Perspective on World’s Largest Picture Screen Announced by RCA Photophone”. International Review of Educational Cinematographic Institute, 1:1 (July): pp. 79–82.

Reeves, Arthur (1929). “Natural Vision Pictures”. The International Photographer, 1:9 (October): pp. 36–37.

Kahane, B. B. (1930). Correspondence to Per John Berggren, Frank H. Hitchcock & George K. Spoor, December 30, 1930. Essanay Film Manufacturing Company records, 1896–1960, Box 24, folder 5, Chicago History Museum, Chicago, IL, United States.

Compare

Related entries

Author

James Layton is a film historian and archivist specializing in the history of motion picture technology. He is Manager of The Museum of Modern Art’s Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center, and is co-author of two books with David Pierce: The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (2015) and King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue (2016). Prior to working at MoMA, Layton was an archivist at George Eastman Museum, where he curated two gallery exhibitions celebrating CinemaScope and Technicolor, and the informational website Technicolor 100. He was project manager of the East Anglian Film Archive’s digital film archive and website relaunch in 2011, and also contributed to the Image Permanence Institute’s Knowing and Protecting Motion Picture Film informational poster (2010). More recently, he contributed a significant chapter on Eastman Kodak to FIAF’s expanded edition of Harold Brown’s Physical Characteristics of Early Films as Aids to Identification (2020).

David Pierce, Kyle Westphal, Chicago History Museum, George Eastman Museum.

Layton, James (2024). “Natural Vision”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.