70mm large-format widescreen process developed at the Fox Film Corporation.

Film Explorer

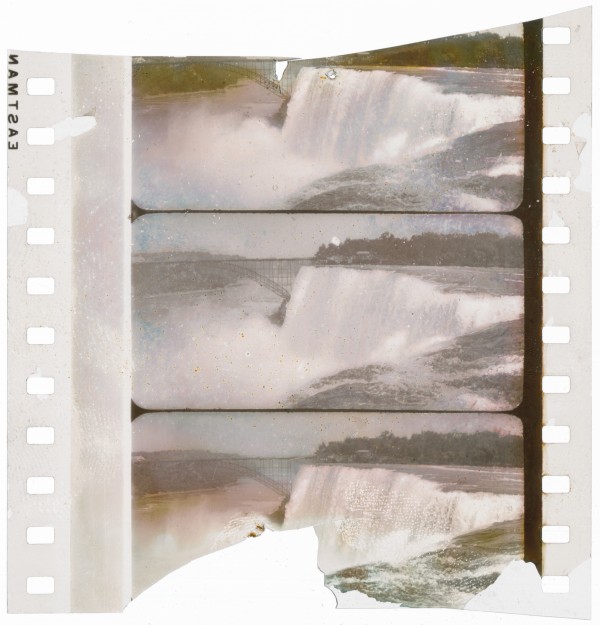

In Niagara Falls (1929), the famous vista was used to display the “grandeur” of Fox’s 70mm format. This short film accompanied screenings of the first two Fox Grandeur features and was particularly well received.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY.

A toned version of Niagara Falls (1929) was used as a demonstration print and also for the first public Grandeur screenings in New York.

Karl Malkames Collection, Scarsdale, NY. Courtesy of Jack Theakston and Bruce Lawton.

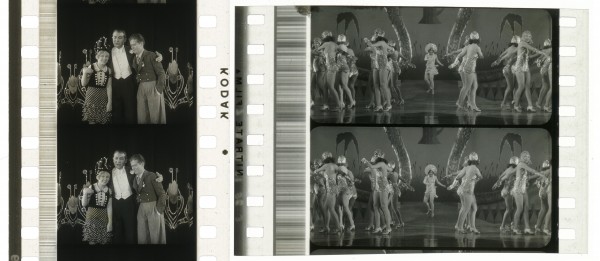

The Tiller Girls appear in a Fox Grandeur Movietone News item that demonstrates how Grandeur’s wide aspect ratio and large screen could replicate a stage show without sacrificing detail.

Karl Malkames Collection, Scarsdale, NY. Courtesy of Jack Theakston and Bruce Lawton.

Unidentified 70mm Fox Grandeur camera test, c. 1929. B/W camera negative. The soundtrack negative was recorded onto a separate roll of film.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA.

Identification

44.91mm x 22.48mm (1.768 in x 0.885 in).

ANSI PH1.20-1956 “American standard dimensions for 70mm unperforated and perforated film for cameras other than motion-picture cameras”, American National Standards Institute, 1956.

B/W. The Niagara Falls short was toned blue.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge print.

19 fps originally; changed to 24 fps by mid-1930.

1

B/W (all exhibited Grandeur films). Some 70mm tests were made by Fox using the two-color Kodachrome process.

None (the Grandeur version of The Big Trail that is available on DVD does not mention Grandeur in the main or end titles).

Movietone optical soundtrack, which was afforded a wider area on the filmstrip (7mm wide, as opposed to the 2mm norm) due to Grandeur’s large format.

48mm x 23.18mm (1.890 in x 0.913 in).

B/W. Panchromatic.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge print.

History

Fox Grandeur was the most prominent of a group of wide-gauge widescreen film formats with which the Hollywood studios experimented in the late 1920s. The brainchild of William Fox and developed at his Fox Film Corporation under the technical direction of Earl I. Sponable (who was also a pioneer in sound-on-film technology), Grandeur employed 70mm film and a 2:1 aspect ratio to produce sharp imagery on large, wide screens. The system was employed for the production and exhibition of a handful of feature films and short subjects. Although its use was suspended in 1930, Fox’s work with Grandeur informed its development of CinemaScope and CinemaScope 55 in the 1950s. More generally, the Hollywood studios’ experimentation with widescreen in this period contributed not only to the widescreen revolution of the 1950s but also to a broader rethinking of film exhibition and film experience throughout the mid-twentieth century.

The Grandeur system emerged against the background of widespread experimentation with mediated sounds and images in the United States in the 1920s. The mid-1920s marked the heyday of large picture palaces seating thousands of people. These theatres had large stages that hosted the live performances that shared billing with filmed entertainment. There were some experiments with expanding the 35mm film image to fit screens of a scale that was commensurate with the proscenia and auditoria at these theatres – for instance, with the Magnascope system. But the 35mm image became grainy when projected on screens larger than 22–24 ft (6.7–7.3m) in width. (Screens averaged about 18 ft wide in this period, though large picture palaces could have 22- to 24-ft-wide screens.) This situation was exacerbated with the arrival of synchronized sound, since sound-on-film systems reduced the area apportioned to the photographic image on the filmstrip and, therefore, forced increased magnification to fill even standard-sized screens. At the same time, synchronized sound was believed to favor the kind of spectacular films demanding a large scope. An additional factor contributing to the interest in wide-gauge widescreen cinema was the popular discourse on television, which was successfully demonstrated at high-profile events in the mid-1920s. The apparently imminent introduction of a new form of screen entertainment, which like radio threatened to draw movie patrons away from the theatre, encouraged movie moguls like William Fox to develop a form of spectacular cinema unachievable in the home (Belton, 1992; Belton, 2010; Paul, 2016; Rogers, 2019).

The Fox Film Corporation’s foray into wide-gauge widescreen cinema was part of its broader efforts at expansion in the mid-1920s, which included acquiring theaters, broadening its newsreels program, and pursuing patents for sound, as well as widescreen technologies. William Fox bought an option for John D. Elms’ Widescope camera in August 1927 and asked Sponable, who headed the studio’s Research Department, to develop it into a more viable widescreen system (while keeping Elms and his assistant William Waddell on the payroll to help with this work). The 70mm Grandeur system debuted at the Gaiety Theatre in New York on September 17, 1929, with a 34-ft-wide screen and a film program that included Fox Movietone Follies of 1929 (directed by David Butler) as well as the short Niagara Falls and several Fox Grandeur Movietone News items. When the second Grandeur feature Happy Days (directed by Benjamin Stoloff) opened at the Roxy Theatre in New York and the Fox Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles in early 1930, the system included 42-ft-wide screens. Although those screens only slightly surpassed the size of the 40-ft screens used for Magnascope, publicity heralded Grandeur as offering a screen twice as wide as older screens. The final feature to be made and shown in Grandeur was Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail, which opened in October 1930. Whereas Fox Movietone Follies of 1929 and Happy Days had harnessed the new screen scope to depict theatrical stage shows, The Big Trail employed it to display spectacular landscapes (Edeson, 1930; Sponable, 1932; Belton, 1992; Belton, 2010; Paul, 2016; Rogers, 2019).

In May 1930, after Fox himself had been ousted from the company, the Fox Film Corporation joined the other studios in agreeing to limit work on their wide-gauge formats until the industry could agree on a technical standard. But by the time a wide-film standard of 50mm was proposed in late 1931, enthusiasm for the format had waned. The studios (still feeling the economic effects of the transition to sound, not to mention the deepening Depression) were financially strained, only a small number of theatres had been equipped for the systems, and the spate of widescreen releases in 1930, including The Big Trail, had failed at the box office (Belton, 1992: pp. 48–64).

Raoul Walsh directs The Big Trail (1930) with the 70mm Grandeur camera visible in the foreground.

Core Collection. Production Files, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, Beverly Hills, CA.

The Big Trail (1930) employed the widescreen format to capture the expansive landscapes of the American West.

Karl Malkames Collection, Scarsdale, NY. Courtesy of Jack Theakston and Bruce Lawton.

Selected Filmography

Feature. 35mm and 70mm Grandeur versions.

Feature. 35mm and 70mm Grandeur versions.

Short. Stories include: “Tiller Girls”, “West Point”, “Scenes of NY Harbor”, “Bill Tilden Wins 7th Tennis Title”, “Feeding Ducks”, “NY to Chicago Express Train” and “Baseball Game”.

Short. Stories include: “Tiller Girls”, “West Point”, “Scenes of NY Harbor”, “Bill Tilden Wins 7th Tennis Title”, “Feeding Ducks”, “NY to Chicago Express Train” and “Baseball Game”.

Feature. 35mm and 70mm Grandeur versions.

Feature. 35mm and 70mm Grandeur versions.

Feature. 35mm and 70mm Grandeur versions.

Feature. 35mm and 70mm Grandeur versions.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Feature. 35mm and 70mm Grandeur versions were shot, but the Grandeur version was never released.

Feature. 35mm and 70mm Grandeur versions were shot, but the Grandeur version was never released.

Technology

The Widescope camera that William Fox initially optioned used an oscillating lens and 57mm film to produce its touted wide scope; however, the Fox Research Department deemed it impractical for studio filmmaking because of “the loss of light in panoraming the lens and the inertia of the moving parts” (Belton, 2010; Schutz, 1988). Instead, Fox technicians set their sights on the 70mm format that would become Grandeur.

Eastman Kodak created special perforations for the 70mm Grandeur film stock, which had a unique pitch of approximately 0.231 in (5.87mm) (as opposed to the pitch of 0.187 in (4.75mm) used for standard 35mm film). Initially Grandeur cameras were planned for silent as well as sound production, but by August 1928 it had been decided that all Grandeur films would have synchronized sound. Fox also conducted experiments using two-color Kodachrome for 70mm production and by mid-1930 it had acquired ten 70mm cameras for color work, though ultimately all exhibited Grandeur films were shot in B/W. The Grandeur system used standard Mitchell sound cameras that had been enlarged to fit the wider stock and that employed a larger shutter and special lenses. The wider stock accommodated an optical soundtrack that was 7mm wide rather than the standard 2mm, the additional width permitting a greater volume range during recording as well as what was touted as better sound quality (Stull, 1930; Edeson, 1930; Color Process Committee, 1930; Schutz, 1988; Rogers, 2019).

The International Projector Corporation produced 70mm Super Simplex projectors to use with the system. The new projectors relocated the shutter between the light source and the film, which enabled the film to remain cooler even with the use of stronger lights. In addition, the film trap and film gate were curved outward toward the aperture in order to prevent the buckling of the film during projection. The optical sound system was similar to standard Movietone systems, and sound playback employed the four-horn Western Electric installation that was also standard at the time (McCullough, 1930; Stull, 1930).

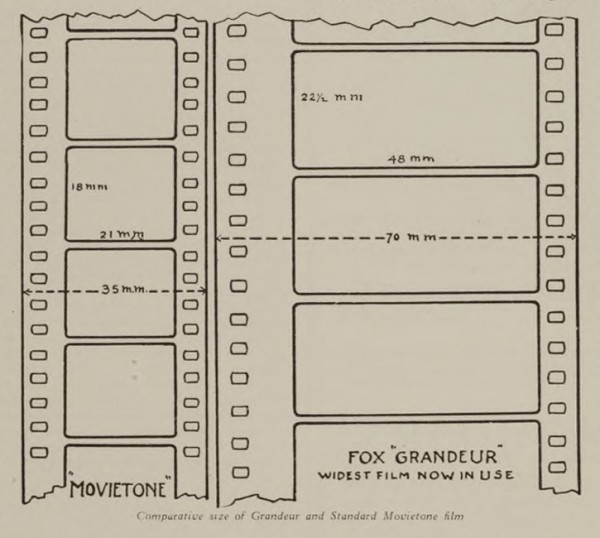

An illustration reproduced in trade journals, including The Motion Picture Projectionist and American Cinematographer, compared the frame dimensions of the 70mm Grandeur format with then-standard 35mm sound film.

William Stull, “Seventy Millimeters”, American Cinematographer, February 1930, p. 43.

A comparison of these filmstrips from the 35mm and 70mm versions of Happy Days (1930) shows the difference in area available for the photographic frame and the optical soundtrack (the latter is positioned to the left of the image).

Left: Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY.

Right: Earl Theisen Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA.

References

Belton, John (2010). “Fox and 50mm Film”. In Widescreen Worldwide, John Belton, Sheldon Hall & Steve Neale (eds), pp. 9–24. New Barnet, Herts, UK: John Libbey.

Belton, John (1992). Widescreen Cinema. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Color Process Committee (1930). Letter to Mr. Sheehan, August 8, 1930. Box 48, “Kodachrome” folder. Earl I. Sponable Papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, NY.

Edeson, Arthur (1930). “Wide Film Cinematography”. American Cinematographer, 11:5 (September).

McCullough, R. H. (1930). “Grandeur Wide Film System”. Motion Picture Projectionist, 3:6 (April).

Paul, William (2016). When Movies Were Theater: Architecture, Exhibition, and the Evolution of American Film. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rogers, Ariel (2019). On the Screen: Displaying the Moving Image, 1926–1942. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schutz, Wayne (1988). “The Grandeur Chronicles: Part 1”. Classic Images, 151 (Jan.): pp. 12–17.

Sponable, Earl I. (1932). Letter to Mr. W. C. Michel, June 24, 1932. Box 10 (General Files Fr-Gr), “Grandeur 1932” folder. Earl I. Sponable Papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, NY.

Stull, William (1930). “Seventy Millimeters”. American Cinematographer, 10:11 (February).

Patents

None

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Ariel Rogers is an associate professor in the Department of Radio/Television/Film at Northwestern University. Her research and teaching address the history and theory of cinema and related media, with a focus on movie technologies, new media, and spectatorship. She is the author of Cinematic Appeals: The Experience of New Movie Technologies (2013) and On the Screen: Displaying the Moving Image, 1926-1942 (2019) as well as essays on topics such as widescreen cinema, digital cinema, special effects, screen technologies, and virtual reality.

The author gratefully acknowledges John Belton for his help with research, James Layton and Crystal Kui for their help with research and images, and Film Atlas’s anonymous reviewers for their feedback.

Rogers, Ariel (2024). “Fox Grandeur”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.