A 50mm, large-format widescreen process developed by the Wide Film Subcommittee of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers in the early 1930s.

Film Explorer

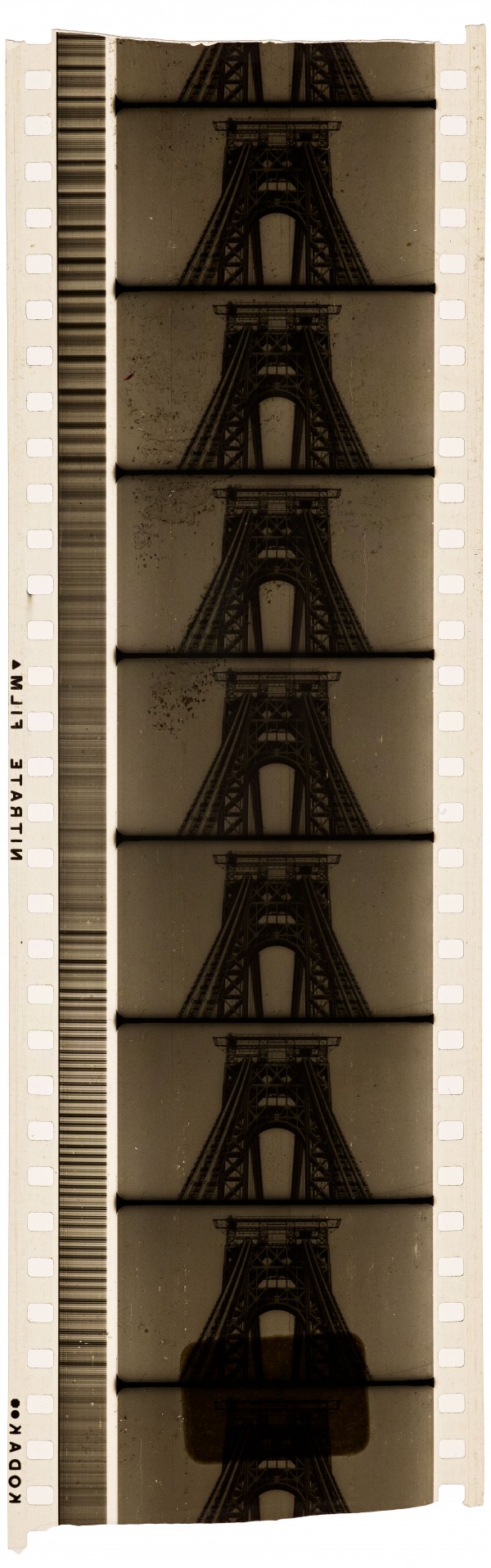

50mm nitrate print of unidentified test footage. The Eastman Kodak edge code (circle, plus) identifies that this stock was manufactured in 1931. A variable-density soundtrack, 0.2 in (5mm) wide, is to the left of the image.

Division of Work and Industry, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, United States.

50mm camera test footage, shot on B/W reversal film by camera manufacturer Ralph G. Fear, c. 1931.

Earl Theisen collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

Identification

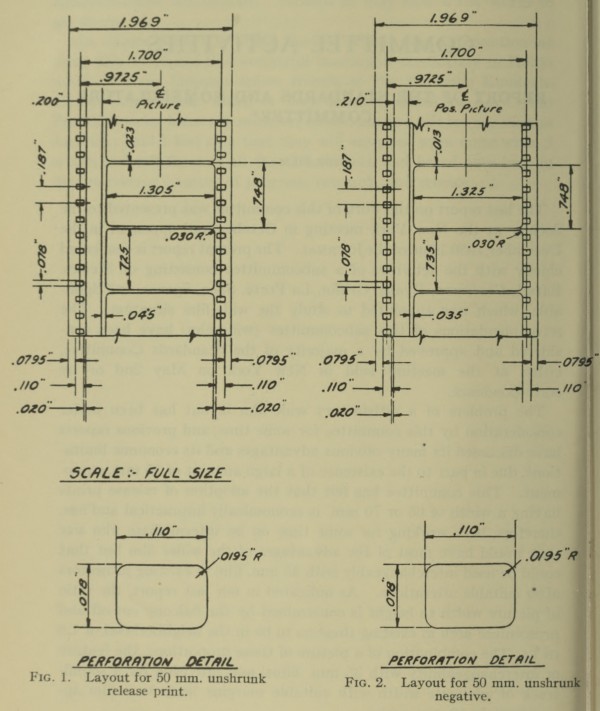

33.15mm x 18.42mm (1.305 in x 0.725 in).

B/W

Standard US Eastman Kodak edge markings and dating symbols in black text.

1

Variable density Movietone track positioned on the left side of the image. The soundtrack width was 0.2 in (5mm).

33.66mm x 18.67mm (1.325 in x 0.735 in).

B/W negative or reversal film.

Standard US Eastman Kodak edge markings and dating symbols in black text.

History

50mm film has its origins in the transition to sound. With sound-on-disc systems, sound was added to the silent image from a discrete source. Sound-on-film systems, however, placed the soundtrack alongside the image track, reducing the image in width from the standard 1.33:1 aspect ratio to 1.15:1. In an attempt to reproduce the standard ratio, projectionists cropped the tops and bottoms of the sound-on-film image and used a special lens to magnify that cropped image so it filled the former screen. Engineers and cinematographers objected that this magnification resulted in images with visible grain. Wide film was a way of generating a better projected image without excessive magnification of film grain. (Allan, 1930) At the same time, large movie palaces with long throws and larger screens had also resulted in a magnification of the image that pushed the limits of the standard 35mm film emulsion. (Stull, 1930)

The 50mm wide film format also accommodated the 2mm width soundtrack used for standard 35mm release prints. Engineers also saw 50mm film as an answer to the impending threat of television, providing audiences with a big-screen entertainment format that was clearly superior to the television screens of the period which were both small and lacking in sharpness. (Belton, 2009). In response to the call for a larger film format, Hollywood turned to the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (SMPE) to come up with an industry-wide standard for wide film. Each studio was working on a different wide-film process. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Fox were making films in 70mm. Warner Bros. and United Artists had begun filming in 65mm film. RKO developed Natural Vision in 63.5mm (2.5 in), while Paramount had a 56mm system called Magnafilm.

On January 27, 1930, the Standards and Nomenclature Committee of the SMPE set up a subcommittee to explore a possible standard for wide film. This committee was chaired by M. C. Batsel, an engineer at RCA Photophone. Arthur Hardy, chair of the Standards Committee, instructed it to do something about “the wide film situation”, emphasizing “the necessity of deciding on a wide film layout with the least possible delay” and reminding members that “If the SMPE is ever to be of any service to the industry, it is certainly right at this time.” (Hardy, 1930)

The subcommittee consisted of several members who were affiliated with Fox and the 70mm standard and some who were affiliated with the Warner Bros./Paramount faction that favored 65mm. After seven meetings spaced over a period of three months, the subcommittee, whose members worked for studios that were promoting wide-film formats as various as 70mm (Fox), 65mm (Warner Bros.), 63.5mm (RKO) and 56mm (Paramount), was unable to agree on a standard for either a wide-film gauge or an aspect ratio. At one point in the deliberations, E. I. Sponable, chief engineer at Fox, suggested a format of 67.5mm, attempting to establish a compromise between the competing formats, but this failed to produce any results. (Sponable, 1930)

When the subcommittee met later in October, it abandoned its earlier focus on 70mm and 65mm and began to explore other possibilities. On October 16, 1930, camera manufacturer Ralph Fear suggested that an intermediate film gauge between 70mm and 35mm might be more suitable for the majority of existing motion picture theaters. Fear suggested 50mm as a standard and the subcommittee agreed that 50mm film could satisfy the wide-film needs of the largest theaters as well (Anon., 1930b). As the subcommittee reported in its summary of Fear’s comments:

“the problem of a satisfactory wide-film layout has been under consideration by this committee for some time, and previous reports have discussed its many obvious advantages and its economic limitations, due in part to the existence of a large amount of 35 mm. equipment. This committee has felt that the adoption of release prints having a width of 65 or 70 mm. is economically impractical and has, therefore, been working for some time on an intermediate film size that would have most of the advantages of the wider film but that could be used interchangeably with 35 mm. film in existing projectors after suitable alterations. As indicated in our last report, the ratio of picture width to height is constrained by the balcony cut-off and proscenium arch in existing theaters to be in the neighborhood of 1.8 to 1. The combination of a picture of these proportions, the feature of interchangeability with 35 mm. films, and provision for a soundtrack of adequate width with suitable margins leads to a film approximately 50 mm. wide.” (Hardy, A. C., 1931).

The new standard, however, was not officially submitted for formal approval “due to the present lack of interest in wide film on the part of the producers.”

At Fox in August 1931, Sponable converted some 70mm equipment to 50mm so that he could film test footage – which he did on A. J. Hallock's duck farm in Speonk, Long Island, NY (Bragg, 1931). Sponable tried to interest Fox in using this converted equipment to film “library” material or stock footage, arguing that it would provide higher-quality images for process shots (Sponable, 1931). Sponable put together a demonstration film on 50mm in June 1932.

In May 1930, the major studios involved with wide-film experimentation met at the Hays Office and agreed to limit their testing of new formats until an independent expert could evaluate aIl the systems and make recommendations as to a potential standard. In December 1930, after the first batch of wide-film releases had failed at the box office, the studios, again acting through the agency of the Hays Office, placed a two-year ban on the introduction of any new formats in an attempt to prevent further costly experimentation before a standard had been agreed upon. The Hays Office agreement reasoned that a conversion to wide-film production would triple production and distribution costs as well as require the alteration and/or rebuilding of 752 of first-run theaters and all of the lesser houses in the world. Under the terms of the agreement, none of the companies experimenting with wide film were permitted to exhibit these films outside of ten key cities, severely restricting their ability to recoup the costs involved in their production and forcing them to release the films in 35mm as well (Belton, 1992). In this way, the studios themselves effectively prevented any widescreen revolution from taking place in the early 1930s.

Selected Filmography

A series of camera tests photographed in 1931 and 1932. Some shots were photographed at A. J. Hallock’s duck farm in Speonk, New York.

A series of camera tests photographed in 1931 and 1932. Some shots were photographed at A. J. Hallock’s duck farm in Speonk, New York.

Technology

One of the chief attractions of 50mm was that it was the widest gauge that could be accommodated by existing theater projection equipment, eliminating expensive replacement costs. A standard 35mm projector could be converted by simply changing sprocket wheels, rollers, the aperture plate, and the doors on the feed and take-up magazines. Projectionists could switch back and forth between 35mm and 50mm after making minimal alterations to the equipment. The chief drawback of the 65mm/70mm gauge was that the majority of projection booths in the country were too small to accommodate both wide-film projectors and standard 35mm equipment. The SMPE subcommittee chose 50mm film (with an aspect ratio of 1.8:1) as “an intermediate film size that would have most of the advantages of wider film but that could be used interchangeably with 35mm film in existing projectors” (Hardy et al., 1931). In other words, 50mm camera and projection equipment had the same image height, spacing between perforations, and positioning of the soundtrack as did standard 35mm equipment, differing solely in terms of image width.

Technical notes:

On Oct 29, 1930, an internal Fox memo from Earl Sponable to Harley Clarke reports that:

1. Sponable converts two Super-Simplex projectors to 50mm projection. Cost: $500 each at International Projector Corp.

2. Sponable asks Fear to complete work on modification of a Simplex projector to a dual 35mm/50mm projector.

3. Sponable asks Eastman Kodak to provide 50mm film as well as a perforator.

4. Fox converts two Bell & Howell semi-automatic printers to 50mm to print 50mm sound and picture from 50mm negative.

5. J. W. Wall agrees to build two 50mm studio cameras.

6. Fox adapts 70mm Grandeur equipment to reduce print Grandeur film to 50mm.

7. Fox converts one existing 35mm Movietone news camera to 50mm.

8. Fox makes a one/two-reel test film in both Grandeur 70mm and 50mm for comparison test screening.

9. 50mm test footage is to be screened at the International Projector Corp. ca. Dec. 11, 1930.

As of April 22, 1931, Fox has (at least) one Fearless 50mm camera and one Wall 50mm camera.

A sketch of the frame design, drawn up by the Wide Film Subcommittee for a 50mm (unshrunk) release print (left) and a 50mm (unshrunk) negative (right).

Hardy, A. C., et al. 1931. “Report of the Standards and Nomenclature Committee (Wide Film Subcommittee)”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (September 1931): pp. 431–434.

References

Allen, Paul (1930). “Wide Film Development”. In Cinematographic Annual (Vol. 1), Hal Hall (ed.). Los Angeles: American Society of Cinematographers.

Anon. (1930a). “The Fearless Silent Super Film Camera”. International Projectionist (April): p. 23.

Anon. (1930b). “Minutes of the Meeting of the Standards and Nomenclature Subcommittee on Wide Film”, October 16, 1930. “SMPE Wide Film Standardization Committee 1930-1931” folder. Earl I. Sponable Papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, NY.

Belton, John (2010). “Fox and 50mm Film”. In Widescreen Worldwide, John Belton, Sheldon Hall & Steve Neale (eds), Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Belton, John (2009). “The Story of 50mm Film”. The Velvet Light Trap, 64 (Fall): pp. 84–86.

Bragg, Herbert (1931). Letter to A. J. Hallock, August 7, 1931. “50mm” folder, Box 8. Earl I. Sponable Papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, NY.

Clarke, Harley L. (1930-1932). Box 5. Earl I. Sponable Papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries. NY.

Hardy, Arthur (1930). Letter to Lawrence Davee, April 26, 1930. “Grandeur” folder. Earl I. Sponable Papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries.

Hardy, A. C., et al. (1931). “Report of the Standards and Nomenclature Committee (Wide Film Subcommittee)”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 17:3 (September): 431–434.

Sherlock, Daniel J. (1997). “The Lost History of Film Formats”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 106:3 (March).

Sponable, E. I. (1930). Letter to Arthur Hardy, April 12, 1930. “SMPE Wide Film Standardization Committee 1930–1931” folder, Box 24. Earl I. Sponable Papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, NY.

Sponable, E. I. (1931). Memo to Harley L. Clarke, June 11, 1931. “50mm” folder, Box 8. Earl I. Sponable Papers. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries NY.

Stull, William (1930). “Seventy Millimeters”. American Cinematographer, 10:11 (February): p.42.

Patents

Fear, Ralph G. 1930. Kinetographic Apparatus, US Patent 1,972,555, filed August 25, 1930, patented September 4, 1934.

Preceded by

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

John Belton is Professor Emeritus of English and Film at Rutgers University. He is editor of the Film and Culture series at Columbia University Press and was former Chair of the Board of Editors of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. He is the author of five books, including Widescreen Cinema (1992), winner of the 1993 Kraszna Krausz prize for books on the moving image, and American Cinema/American Culture (1994–2022), a textbook written to accompany the PBS series American Cinema. He earned his PhD in Classical Philology from Harvard University and specializes in film history and cultural studies. Belton has served on the National Film Preservation Board and as Chair of the Archival Papers and Historical Committee of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. In 2005/06, he was granted a Guggenheim Fellowship to pursue his study of the use of digital technology in the film industry.

Thanks to James Layton and Crystal Kui for their editorial guidance.

Belton, John (2024). “50mm”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.